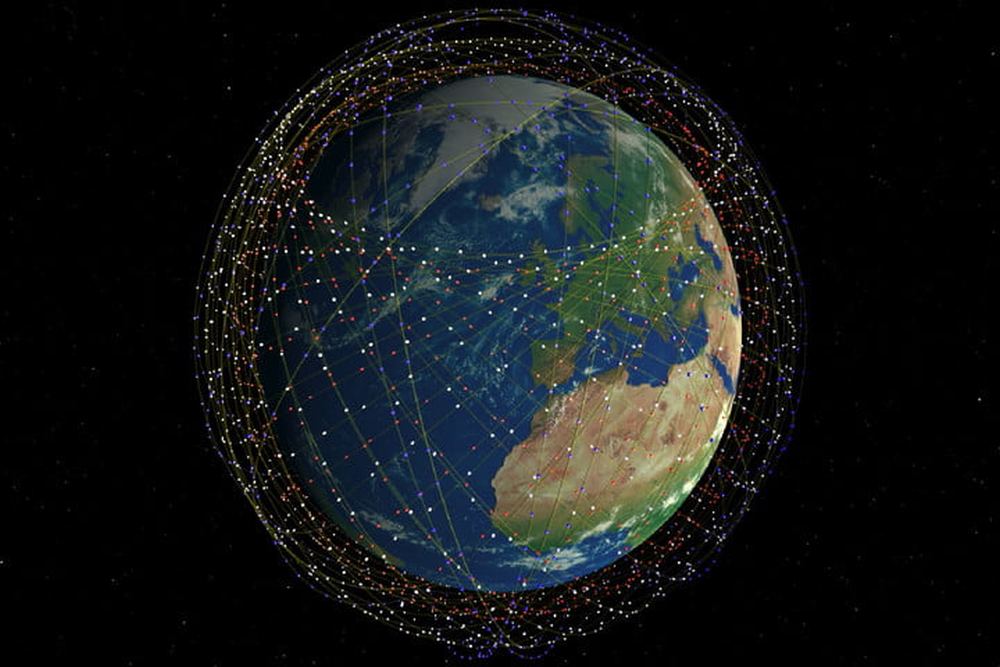

Picture the space around Earth filled with tens of thousands of communications satellites. That scenario is slowly coming into being, and it has astronomers concerned. Now a group of astronomers have written a paper outlining their detailed concerns, and how all of these satellites could have a severe, negative impact on ground-based astronomy.

Continue reading “Astronomers Have Some Serious Concerns About Starlink and Other Satellite Constellations”Underwater Robot Captures its First Sample 500 Meters Below the Surface of the Ocean

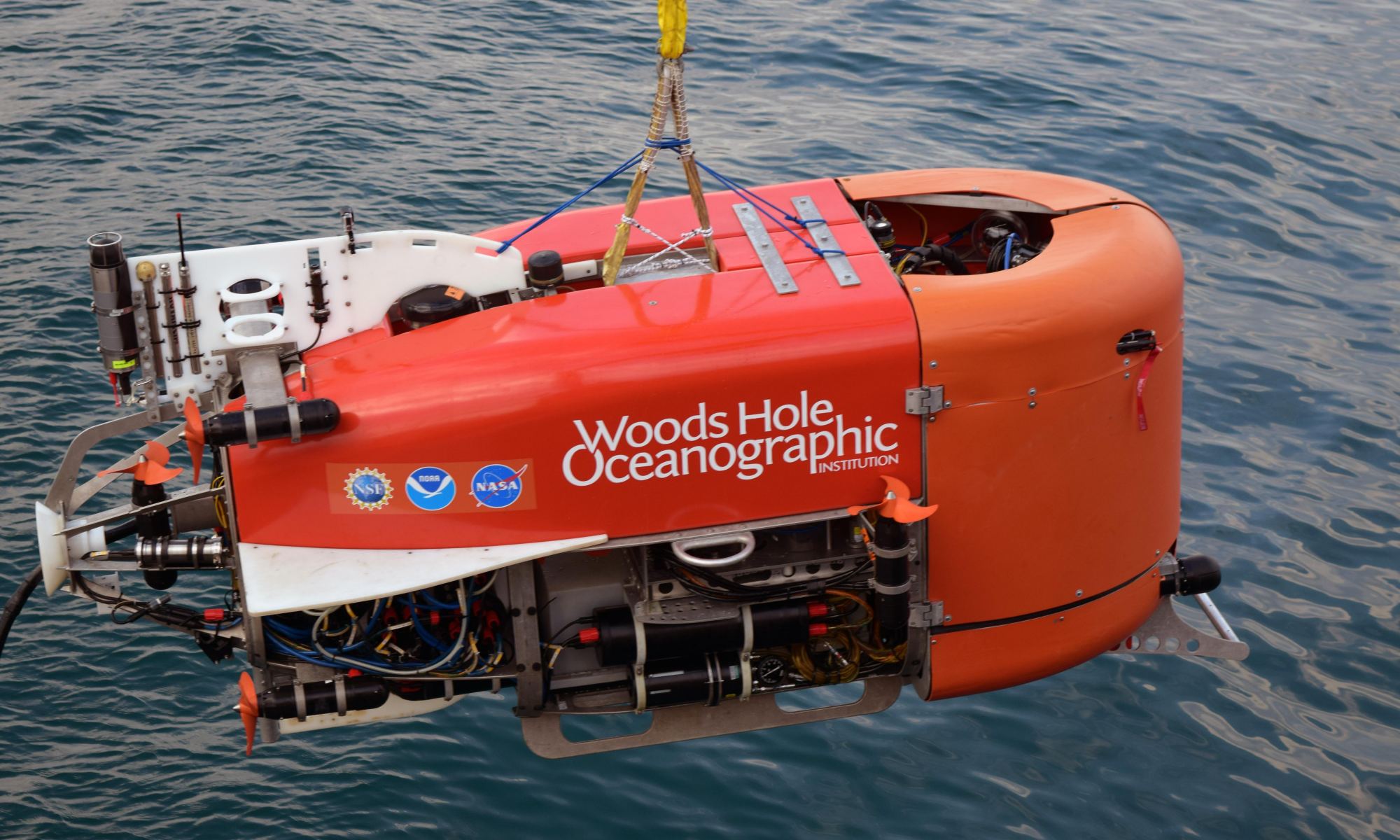

The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) says their underwater robot has just completed the first-ever automated underwater sampling operation. The robot is called Nereid Under Ice (NEI) and it collected the sample in Greece. WHOI is developing Nereid in association with NASA’s Planetary Science and Technology from Analog Research (PSTAR) program.

Continue reading “Underwater Robot Captures its First Sample 500 Meters Below the Surface of the Ocean”If Astronauts Hibernated on Long Journeys, They’d Need Smaller Spacecraft

There’s a disturbing lack of hibernation in our space-faring plans. In movies and books, astronauts pop in and out of hibernation—or stasis, or cryogenic sleep, or suspended animation, or something like it—on a regular basis. If we ever figure out some kind of hibernation, can we take advantage of it to get by with smaller spacecraft?

The European Space Agency (ESA) is working to answer that question.

Continue reading “If Astronauts Hibernated on Long Journeys, They’d Need Smaller Spacecraft”Stingray Glider to Explore the Cloudtops of Venus

Venus is colloquially referred to as “Earth’s Twin”, owing to the similarities it has with our planet. Not surprisingly though, there is a great deal that scientists don’t know about Venus. Between the hot and hellish landscape, extremely thick atmosphere, and clouds of sulfuric rain, it is virtually impossible to explore the planet’s atmosphere and surface. What’s more, Venus’ slow rotation makes the study of its “dark side” all the more difficult.

However, these challenges have spawned a number of innovative concepts for exploration. One of these comes from the University of Buffalo’s Crashworthiness for Aerospace Structures and Hybrids (CRASH) Laboratory, where researchers are designing a unique concept known as the Bio-inspired Ray for Extreme Environments and Zonal Explorations (BREEZE).

Continue reading “Stingray Glider to Explore the Cloudtops of Venus”Skylon’s SABRE Engine Passes a Big Test

The UK aerospace company Reaction Engine Limited was founded in 1989 for the express purpose of creating engines that would lead to spaceplanes capable of horizontal take-off and landing (HOTOL). With support from the ESA, these efforts have resulted in the Synergetic Air-Breathing Rocket Engine (SABRE). Once complete, this system will combine elements of jet and rocket propulsion to achieve hypersonic speeds (Mach 5 to Mach 25).

Recently, Reaction Engines passed a major milestone with the development of their SABRE engine. As the company announced earlier this week (on Tues. Oct. 22nd), their engineers conducted a successful test of a vital component – the engine’s heat exchange element (aka. precooler). What’s more, the test involved airflow temperatures equivalent to speeds of Mach 5, which is in the hypersonic range.

Continue reading “Skylon’s SABRE Engine Passes a Big Test”A Private Company in China Plans to Launch Reusable Rockets by 2021

A Chinese company is planning to launch a rocket with a reusable booster in 2021. The company is called i-Space, and the rocket is called Hyperbola-2. They’ve already developed and launched another rocket, called Hyperbola.

Continue reading “A Private Company in China Plans to Launch Reusable Rockets by 2021”An Army of Tiny Robots Could Assemble Huge Structures in Space

We live in a world where multiple technological revolutions are taking place at the same time. While the leaps that are taking place in the fields of computing, robotics, and biotechnology are gaining a great deal of attention, less attention is being given to a field that is just as promising. This would be the field of manufacturing, where technologies like 3D printing and autonomous robots are proving to be a huge game-changer.

For example, there is the work being pursued by MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA). It is here that graduate student Benjamin Jenett and Professor Neil Gershenfeld (as part of Jenett’s doctoral thesis work) are working on tiny robots that are capable of assembling entire structures. This work could have implications for everything from aircraft and buildings to settlements in space.

Continue reading “An Army of Tiny Robots Could Assemble Huge Structures in Space”NASA’s New Lunar Spacesuit is Going to be a Lot More Comfortable for Astronauts

NASA is developing new spacesuits for their Artemis program. The new suits will give the astronauts greater mobility, will be safer, and will be designed from the ground up to fit women.

Continue reading “NASA’s New Lunar Spacesuit is Going to be a Lot More Comfortable for Astronauts”A Satellite Just Launched Whose Job is to Extend the Life of Geosynchronous Satellites

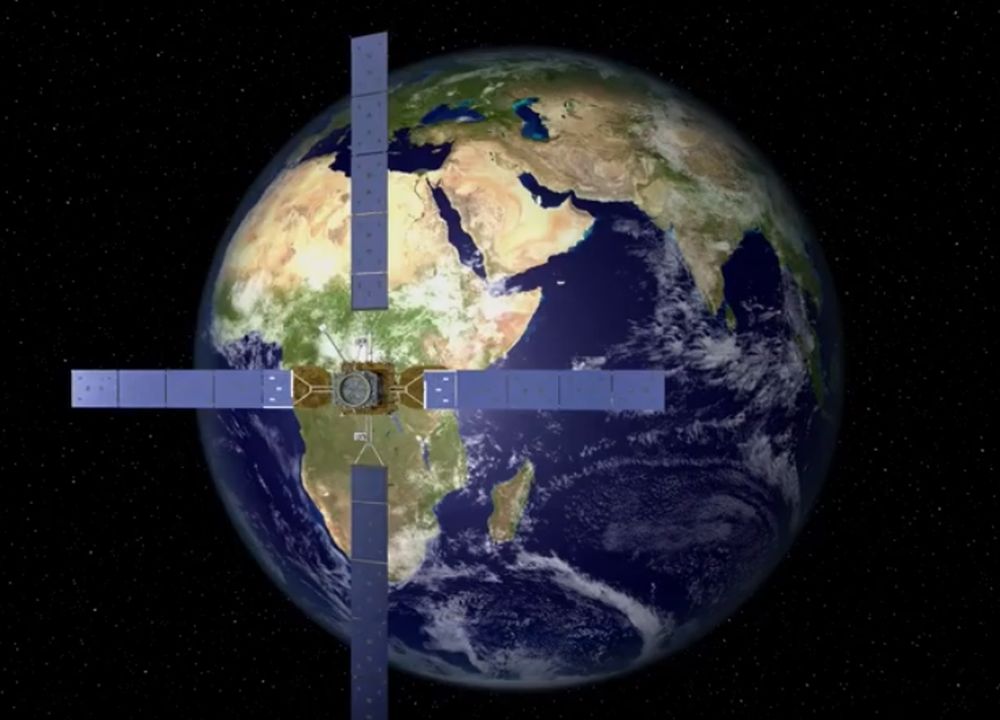

Space Logistics LLC, a subsidiary of Northrop Grumman, has launched a satellite that can extend the life of other satellites. The satellite is called MEV-1, or Mission Extension Vehicle-1. MEV-1 is the first of its kind.

Continue reading “A Satellite Just Launched Whose Job is to Extend the Life of Geosynchronous Satellites”This is What Moondust Looks Like When You Remove All the Oxygen. A Pile of Metal

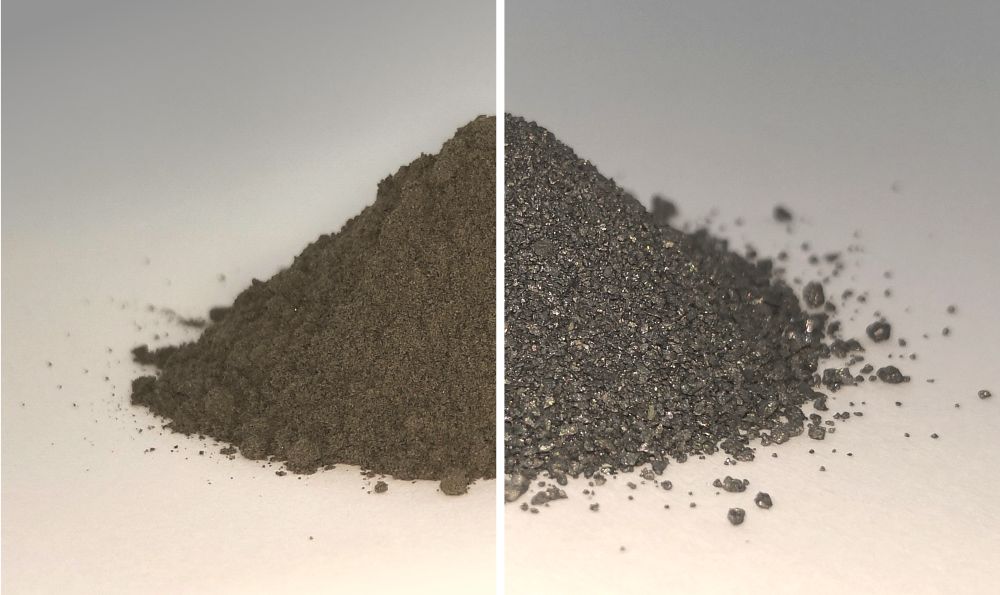

The Moon has abundant oxygen and minerals, things that are indispensable to any space-faring civilization. The problem is they’re locked up together in the regolith. Separating the two will provide a wealth of critical resources, but separating them is a knotty problem.

Continue reading “This is What Moondust Looks Like When You Remove All the Oxygen. A Pile of Metal”