Maybe you can’t climb on a rocketship to Mars, at least yet, but at the least you can get your desire for exploration out through other means. Today, take comfort that humanity is sending 90,000 messages in the Red Planet’s direction. That’s right, the non-profit Uwingu plans to transmit these missives today around 3 p.m. EST (8 p.m. UTC).

Among the thousands of ordinary folks are a collection of celebrities: Bill Nye, the Science Guy; George Takei (“Sulu” on Star Trek) and commercial astronaut Richard Garriott, among many others.

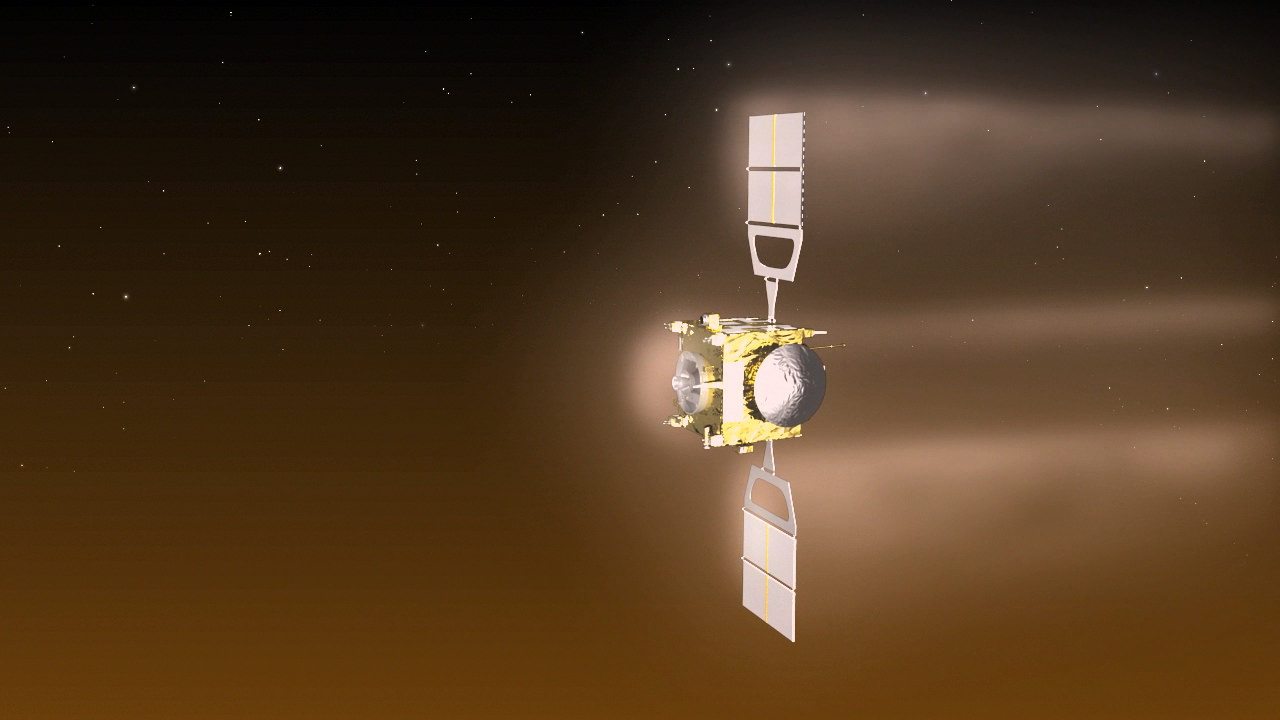

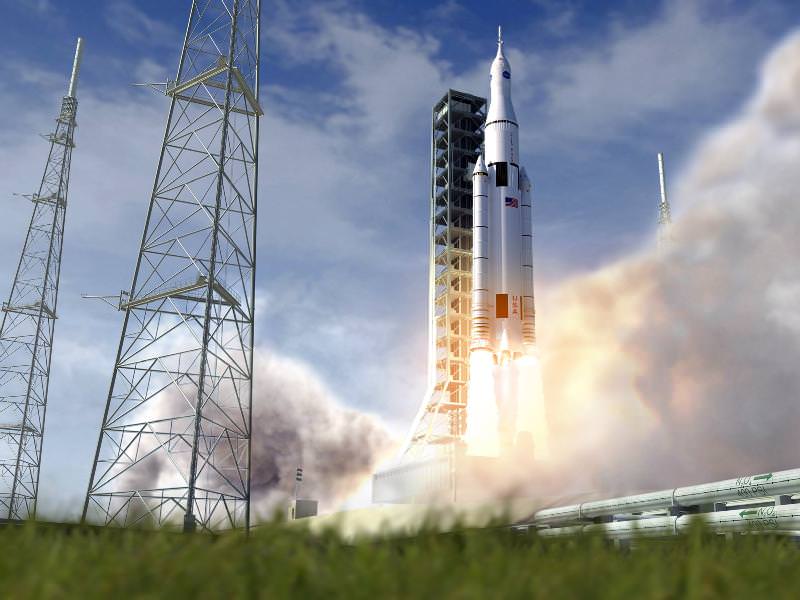

“This is the first time messages from people on Earth have been transmitted to Mars by radio,” Uwingu stated. “The transmission, part of Uwingu’s ‘Beam Me to Mars’ project, celebrates the 50th anniversary of the 28 November 1964 launch of NASA’s Mariner 4 mission—the first successful mission to explore Mars.”

The project was initially released in the summer with the idea that it could help support struggling organizations, researchers and students who require funding for their research. The messages cost between $5 and $100, with half the money going to the Uwingu Fund for space research and education grants, and the other half for transmission costs to Mars and other needed things.

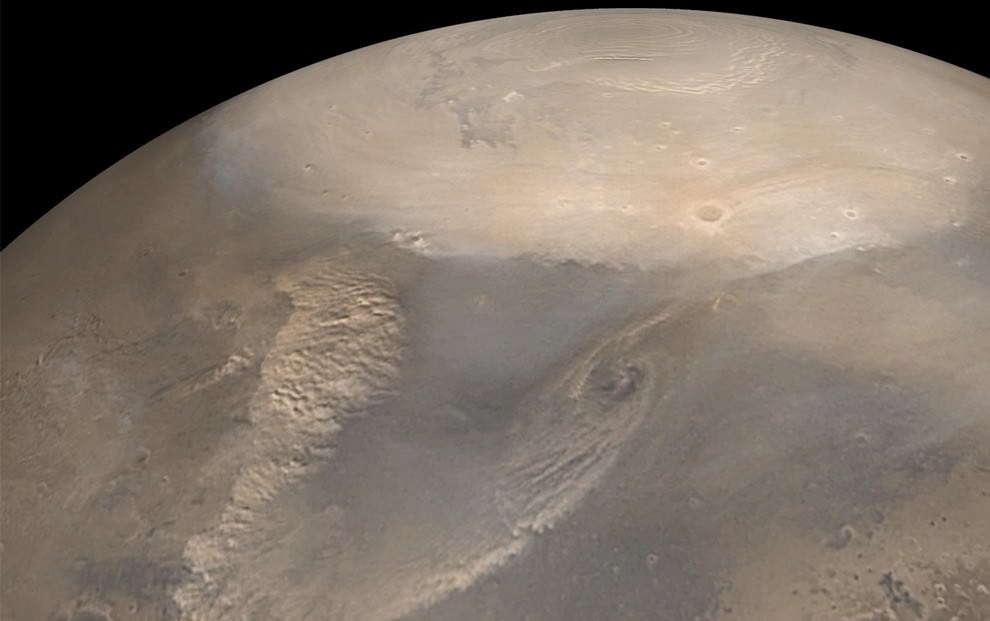

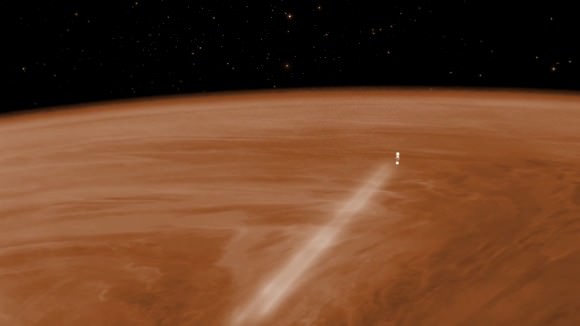

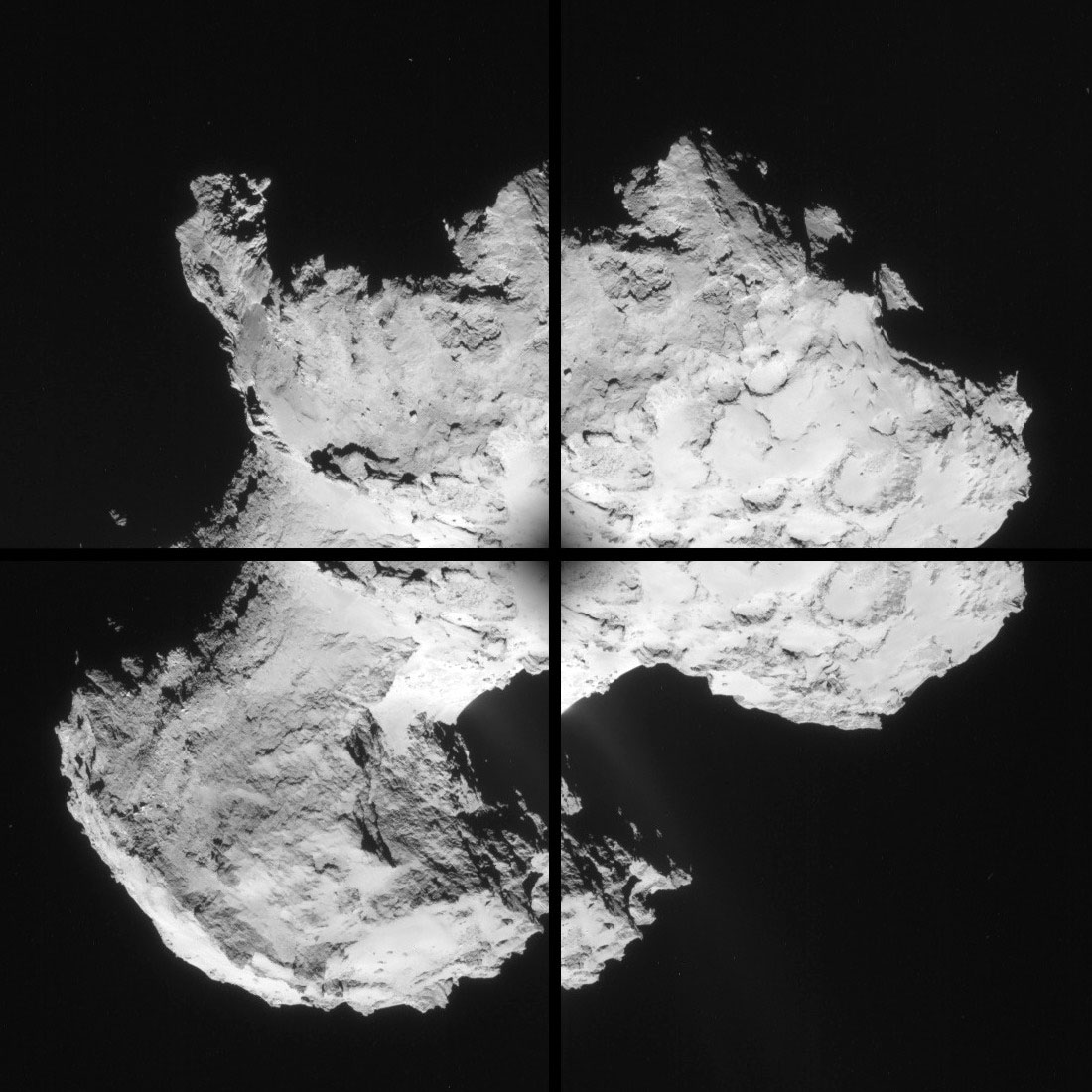

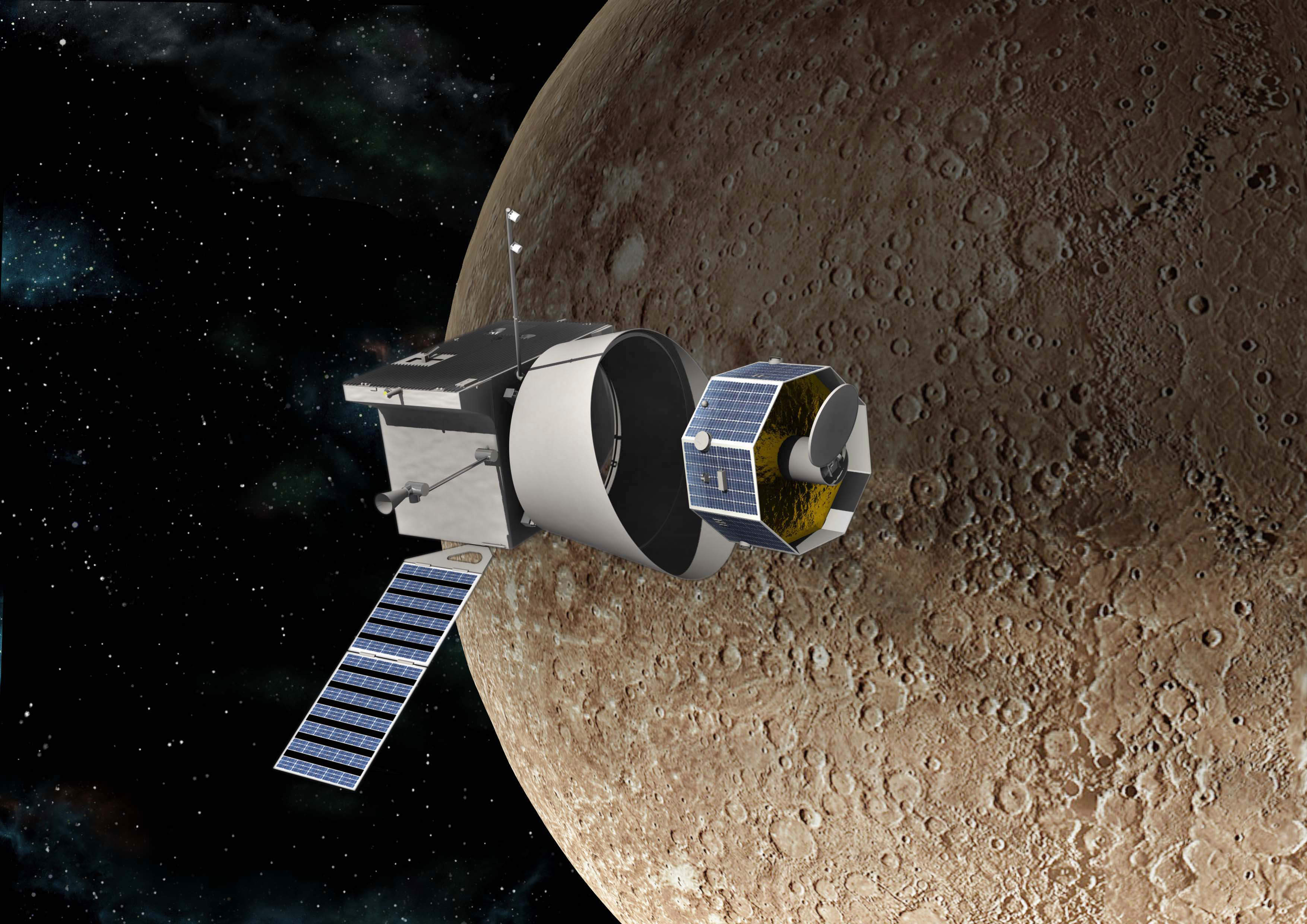

While only robots can receive those messages for now, it’s another example of transmission between the planets that we take for granted. For example, check out this stunning picture below from Mars Express, a European Space Agency mission, that was just released yesterday (Nov. 27). Every day we receive raw images back from the Red Planet that anyone can browse on the Internet. That was unimaginable in Mariner 4’s days. What will we see next?