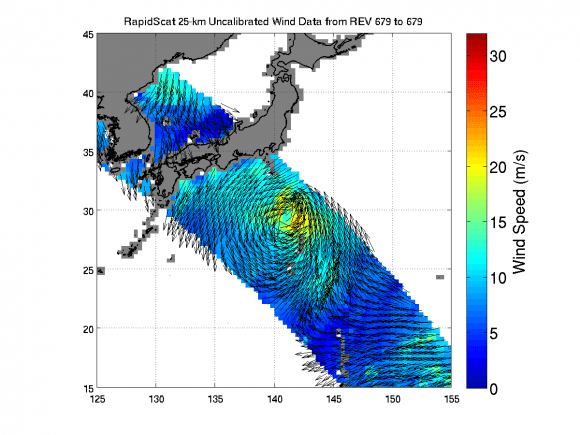

Barely two months after being launched to the International Space Station (ISS), NASA’s first science payload aimed at conducting Earth science from the station’s exterior has started its ocean wind monitoring operations two months ahead of schedule.

Data from the ISS Rapid Scatterometer, or ISS-RapidScat, payload is now available to the world’s weather and marine forecasting agencies following the successful completion of check out and calibration activities by the mission team.

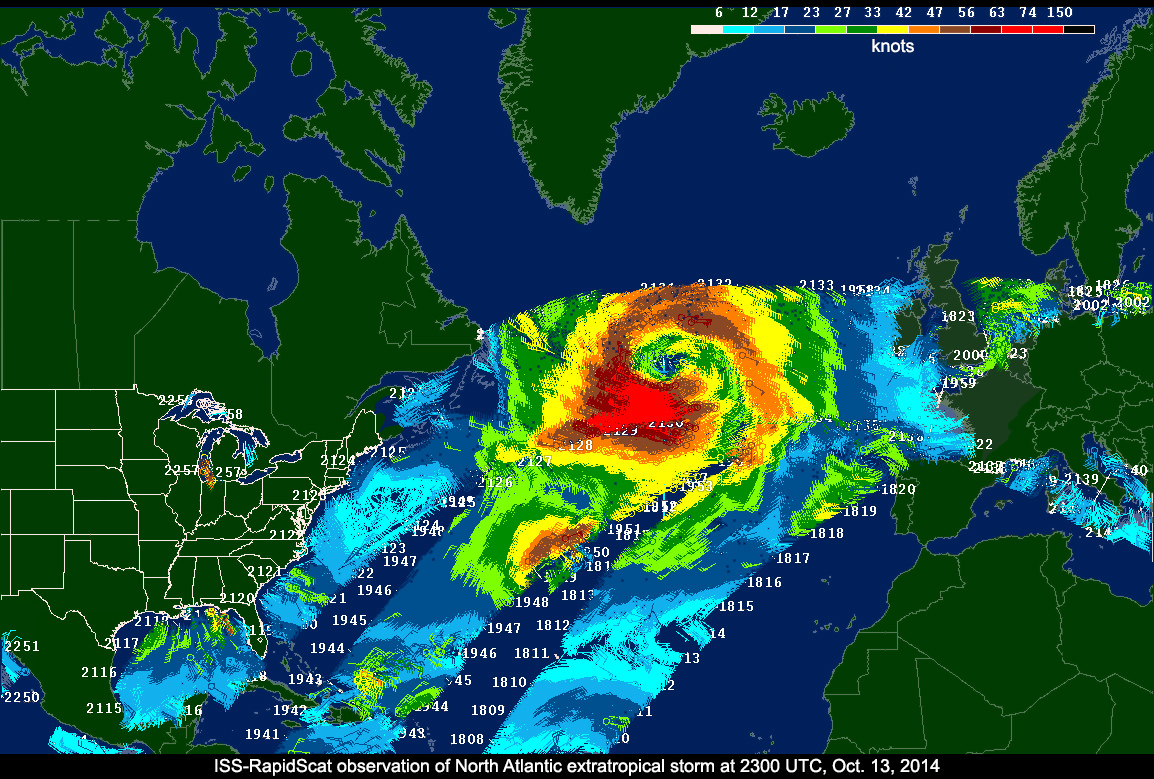

Indeed it was already producing high quality, usable data following its power-on and activation at the station in late September and has monitored recent tropical cyclones in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans prior to the end of the current hurricane season.

RapidScat is designed to monitor ocean winds for climate research, weather predictions, and hurricane monitoring for a minimum mission duration of two years.

“RapidScat is a short mission by NASA standards,” said RapidScat Project Scientist Ernesto Rodriguez of JPL.

“Its data will be ready to help support U.S. weather forecasting needs during the tail end of the 2014 hurricane season. The dissemination of these data to the international operational weather and marine forecasting communities ensures that RapidScat’s benefits will be felt throughout the world.”

The 1280 pound (580kilogram) experimental instrument was developed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It’s a cost-effective replacement to NASA’s former QuikScat satellite.

The $26 million remote sensing instrument uses radar pulses reflected from the ocean’s surface at different angles to calculate the speed and direction of winds over the ocean for the improvement of weather and marine forecasting and hurricane monitoring.

The RapidScat, payload was hauled up to the station as part of the science cargo launched aboard the commercial SpaceX Dragon CRS-4 cargo resupply mission that thundered to space on the company’s Falcon 9 rocket from Space Launch Complex-40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida on Sept. 21.

ISS-RapidScat is NASA’s first research payload aimed at conducting near global Earth science from the station’s exterior and will be augmented with others in coming years.

It was robotically assembled and attached to the exterior of the station’s Columbus module using the station’s robotic arm and DEXTRE manipulator over a two day period on Sept 29 and 30.

Ground controllers at Johnson Space Center intricately maneuvered DEXTRE to pluck RapidScat and its nadir adapter from the unpressurized trunk section of the Dragon cargo ship and attached it to a vacant external mounting platform on the Columbus module holding mechanical and electrical connections.

The nadir adapter orients the instrument to point its antennae at Earth.

The couch sized instrument and adapter together measure about 49 x 46 x 83 inches (124 x 117 x 211 centimeters).

“The initial quality of the RapidScat wind data and the timely availability of products so soon after launch are remarkable,” said Paul Chang, ocean vector winds science team lead at NOAA’s National Environmental Satellite, Data and Information Service (NESDIS)/Center for Satellite Applications and Research (STAR), Silver Spring, Maryland.

“NOAA is looking forward to using RapidScat data to help support marine wind and wave forecasting and warning, and to exploring the unique sampling of the ocean wind fields provided by the space station’s orbit.”

This has been a banner year for NASA’s Earth science missions. At least five missions will be launched to space within a 12 month period, the most new Earth-observing mission launches in one year in more than a decade.

ISS-RapidScat is the third of five NASA Earth science missions scheduled to launch over a year.

NASA has already launched the of the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory, a joint mission with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, in February and the Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) carbon observatory in July 2014.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.