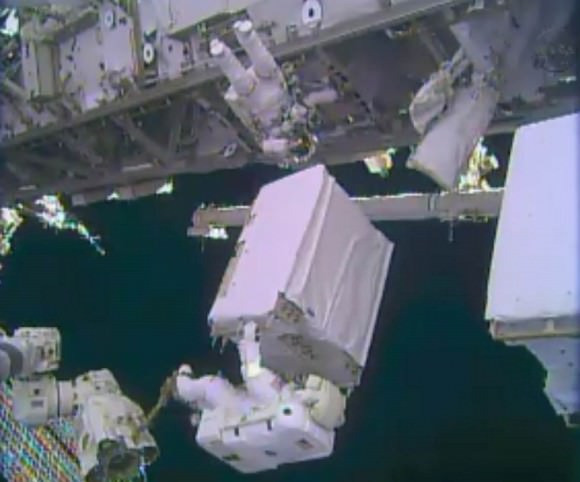

Astronauts on the International Space Station “could have ignited flammable materials” on station while drying out a spacesuit that experienced a major leak during a spacewalk in July 2013, a new report reveals.

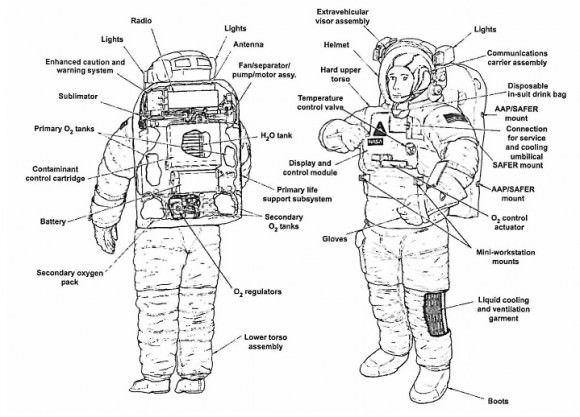

NASA Mission Control directed the Expedition 36 crew to use a vacuum cleaner to suction out the water, a procedure that inadvertently sucked up oxygen from the suit’s secondary high pressure oxygen tank, says a mishap report into the spacesuit leak incident. This “potentially hazardous risk” of electricity and pure oxygen created a fire hazard, the report added.

In a phone call with reporters yesterday (Feb. 27), report chair Chris Hansen added that the “levels of oxygen were perfectly safe” in this particular incident and that the “the risk to the crew in the end was none”, but said the incident still warranted attention in the 222-page report, which mainly deals with the spacesuit leak.

The incident occurred on July 17, 2013, one day after a “life-threatening” amount of water leaked into a spacesuit helmet used by Luca Parmitano, the report said. The astronauts and NASA were doing looking for the source of the leak. Astronauts reported no damage to the water bag and no water in the suit (which had been cleaned up after the spacewalk).

Next, they turned on the fan to the portable life support system (or backpack) with a secondary oxygen pack (SOP) check-out fixture. The fixture covered a vent port and oxygen switch for about 14 minutes. All appeared to be running normally, with no water detected. When the crew then removed the fixture (following procedure), they heard a “sucking” noise and the fan ceased moving, the report said.

“The crew was directed to turn off the suit fan and move the O2 Actuator to OFF. The crew then turned the suit fan back ON and again set the O2 Actuator to [the] IV [setting]. The fan briefly began spinning and then shut down almost immediately, with the crew reporting a water “sucking” or “gurgling” sound,” the report added.

The crew found “a few drops” of water in a canister outlet and “about a spoonful” of water in the suit inlet ports, as well as a few drops of water in a neck vent port. As the ground decided what to do, an infrared carbon-dioxide transducer in the suit “began to show an increase in its reading and eventually went off-scale high, most likely due to moisture in the vent loop near the CO2 [carbon dioxide] transducer,” the report stated.

With water in the suit, Mission Control then asked the crew to remove the water with a vacuum (one that is designed for wet or dry cleanup) as soon as the astronauts had the chance. Everything was normal until after the station emerged from a routine loss of signal, at which point controllers saw the secondary oxygen pack was turned on and reading 500 pounds per square inch lower than before the loss of communication.

“They quickly realized that their procedure had resulted in the EMU releasing 100% oxygen from the SOP into the vent loop, which was then sucked into the vacuum cleaner. This was a potentially dangerous situation involving unintended consequences,” the report said.

“During interviews, system experts indicated that they should have been able to anticipate SOP activation due to the reduced pressure created by the vacuum cleaner. The procedure was immediately stopped. No fire occurred and the crew was not harmed.”

In interviews after the incident, individuals spoke of “perceived pressure” to do the dry-out procedure quickly instead of first testing it on the ground with similar hardware. They instead used a non-functional spacesuit before directing the crew to do the procedure.

There were at least three factors contributing to that pressure, the report added: the desire to avoid corrosion in the suit, limited crew time, and the impending loss of signal.

The report did not identify any “additional causes, findings, or observations” from this event, noting that it is not technically an anomaly and was not classified as such in the NASA literature.

You can read the full report here. As for the spacewalk mishap investigation, some of the major findings showed it took 23 minutes to order Parmitano back to the airlock, and that water was seen as a normal thing in spacesuit helmets.