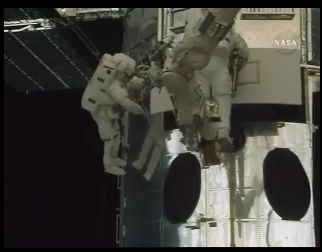

It has been a busy day in space and here are a few jottings about what all has been going on. Above, you can watch the spectacular videos taken by cameras mounted on the shuttle’s solid rocket boosters, taken during the launch of Atlantis on the current Hubble Servicing Mission. It’s a crazy ride, tagging along on the outside of the shuttle going up, and spinning dizzily on the way down until splashing in the ocean. Not for the faint of heart! But seeing the SRB videos means only one thing: Atlantis and the STS-125 crew have been cleared to land. NASA has carefully reviewed the videos and the data from the crew’s scan of the shuttle’s thermal protection system, saying there are absolutely no issues that would preclude the shuttle from landing. Weather, however could be another matter, which is why NASA ordered the shuttle to power down for awhile today to save on consumables. Predicted weather does not look good for landing on Friday, so the crew will make sure they have enough power to stay in orbit for a few more days.

Now about that toast…

[/caption]

A huge crowd gathered in the space station mission control room at Johnson Space Center today as the ISS crew was given a “go” to drink water that the new recycling system has purified. Everyone joined in at mission control with a toast to the success of the recycling system, giving a nod to everyone who helped create the system, install it on the ISS and work on getting the fussy system to run. This is big news, as it means the station is ready to handle the increased crew size of 6 astronauts.

Also:

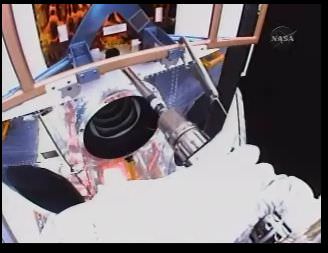

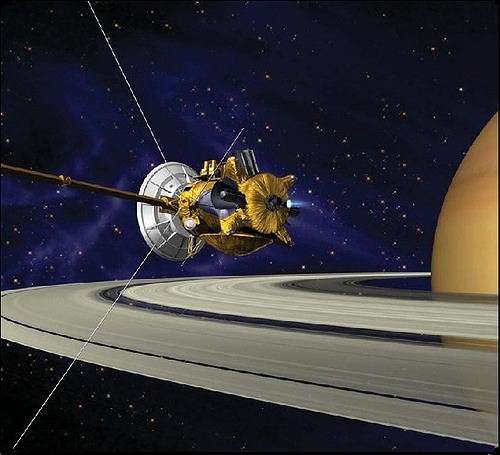

The STS-125 crew held a press conference from the shuttle today. The highlight was Mike Massimino talking about how he ripped a handrail off of Hubble in order to proceed with the scheduled repair of the STIS instrument.

“Ripping that thing out of there was quite an experience, and I’m glad it led to a successful repair,” said Massimino, who added that he drew inspiration from his uncle Frank, who once ripped an oil filter out a car. “That was pretty close to what was going on with Hubble.”

Later, during a ship-to-ship call between Atlantis and the ISS, space station crew member Michael Barrett revisited Massimino’s special touch.

“The magic Massimino touch is now legendary, and we’re looking forward to seeing you guys back on the ground,” he said.

If you missed the crew news conference, its available here. Additionally, the discussion between the two crews, can be seen here.

Update: One other piece of news from the shuttle is that President Obama called the STS-125 crew to congratulate them on a job well done. “I wanted to personally tell you how proud I am of all of you and everything that you’ve accomplished,” he said.

“Like a lot of Americans, I’ve been watching with amazement the gorgeous images you’ve been sending back and the incredible repair mission you’ve been making in space,” he said. “I think you’re providing a wonderful example of the kind of dedication and commitment to exploration that represents America and the space program generally. These are traits that have always made this country strong and all of you personify them.”

Obama also said he would be naming a new NASA administrator very soon, but wouldn’t say who it is.

“Just so we’re sure, the new administrator is not any of us on the flight deck right now, is it?” asked Commander Scott Altman (Altman had suggested Hubble fix-it man John Grunsfeld for administrator earlier this week.)

“I’m not going to give you any hints,” Obama said with a laugh.

“Thank you very much, fair enough, sir,” Altman replied.

Listen to the audio and/or read the transcript of Obama’s call here.

One other spaceflight news tidbit, Orbital Sciences Corp. finally launched a Minotaur 1 rocket from the Wallops Island Flight Facility with the Tactical Satellite-3 (TacSat-3) satellite. The launch was heavily postponed, with several scrubs relating from the weather to the launch vehicle and facility. Find out more about the launch and the satellite here.