[/caption]

The Senate Budget Committee has given the green light to fund NASA’s shuttle program past the end of 2010, when the program is set to retire.

But NASA isn’t asking for an extension.

Florida Sen. Bill Nelson requested the $2.5 billion provision, which was included in the broader five-year spending plan that passed committee Monday afternoon. His office argues that launching nine missions in 18 months puts too much pressure on the agency, and could compromise safety.

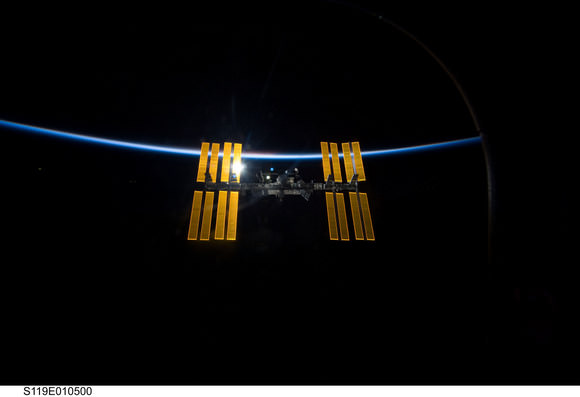

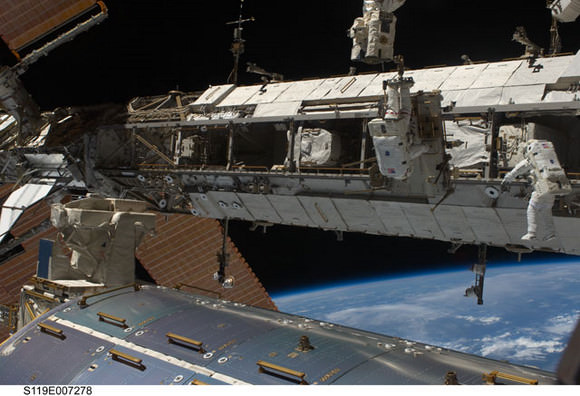

NASA is preparing to launch the shuttle Atlantis on May 12 for a servicing mission of the Hubble Space Telescope, and the eight remaining missions are dedicated to completing the International Space Station.

“We are confident that we can fly out the shuttle manifest before the end of 2010,” said John Yembrick, a spokesman out of NASA’s Washington headquarters.

Nelson’s office isn’t as optimistic.

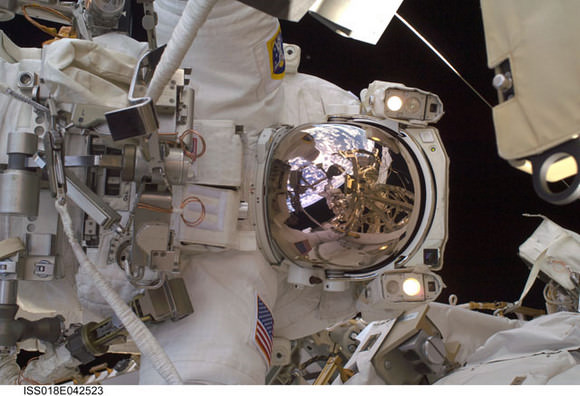

“Given that there are roughly only 18 months but nine flights left, we have a concern that may be unrealistic,” said Dan McLaughlin, a spokesman for Nelson’s office. He cited the Challenger and Columbia accidents, where “the investigation board in both cases identified scheduling pressure as a contributing factor to those accidents.”

In the past, NASA has been “overly optimistic about schedules for shuttle missions,” McLaughlin said. But in reality, the agency has gotten four or five launches off the ground in each of the past several years. “It doesn’t take but a bad hurricane season and the best laid plans can fall apart. Could NASA do it? Yeah. But a lot of things would have to go right.”

The $2.5 billion provision, if it passes the full Senate and House, would alleviate the pressure, Nelson thinks, by opening up the possibility for additional funding in 2011 — and allow NASA to proceed with safety as a first concern. The measure would soften a firm line both the Bush and Obama administrations have taken on retiring the program by the end of 2010.

The Budget Committee’s decision sends a strong signal that the shuttle shouldn’t be retired on a date-certain, but only when all the missions are completed, Nelson reportedly said immediately after the Thursday vote.

Meanwhile, NASA is looking forward to the next generation of launch vehicles, Orion (above, concept credit Lockheed Martin Corp.) and the Ares series. The vehicles are designed to return people to the moon — and perhaps even Mars — to live and explore. The first Ares test flight is planned for later this year.

The gap between the planned shuttle retirement in 2010, and the availability of the next generation launch vehicles, will be five years. During that time the United States is likely to partner with Russia to use Soyuz launch vehicles for low-orbit work and as the space station’s docked emergency vehicle — which is part of the astronauts’ escape plan in the event of debris hits or other dangers aboard the ISS.

It is also possible that commercial vehicles could rise to the challenge before 2015, NASA’s Yembrick said. NASA has awarded two contracts to companies that will deliver cargo to the space station after the retirement of the space shuttle: Orbital Sciences Corp. of Dulles, Virginia, and Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX) of Hawthorne, California.

“Once they’ve proven that they can successfully deliver cargo, we also may one day look at purchasing crew services,” Yembrick said. “We don’t want to speculate when that may occur.”

Sources: Spaceref, interviews with Dan McLaughlin and John Yembrick.