[/caption]

The space shuttles are slated to be retired in September of 2010. NASA put out a call recently to ask what should be done with the shuttles post-retirement, and many think they should be put in museums or on display in rocket parks. But futurist and entrepreneur Eric Knight, (founder of UP Aerospace and Remarkable Technologies) has a somewhat novel idea of what to do with the shuttles after they are done with their current duties: Send them to Mars. He says his formula is simple and will allow humans to travel to Mars in years, not decades.

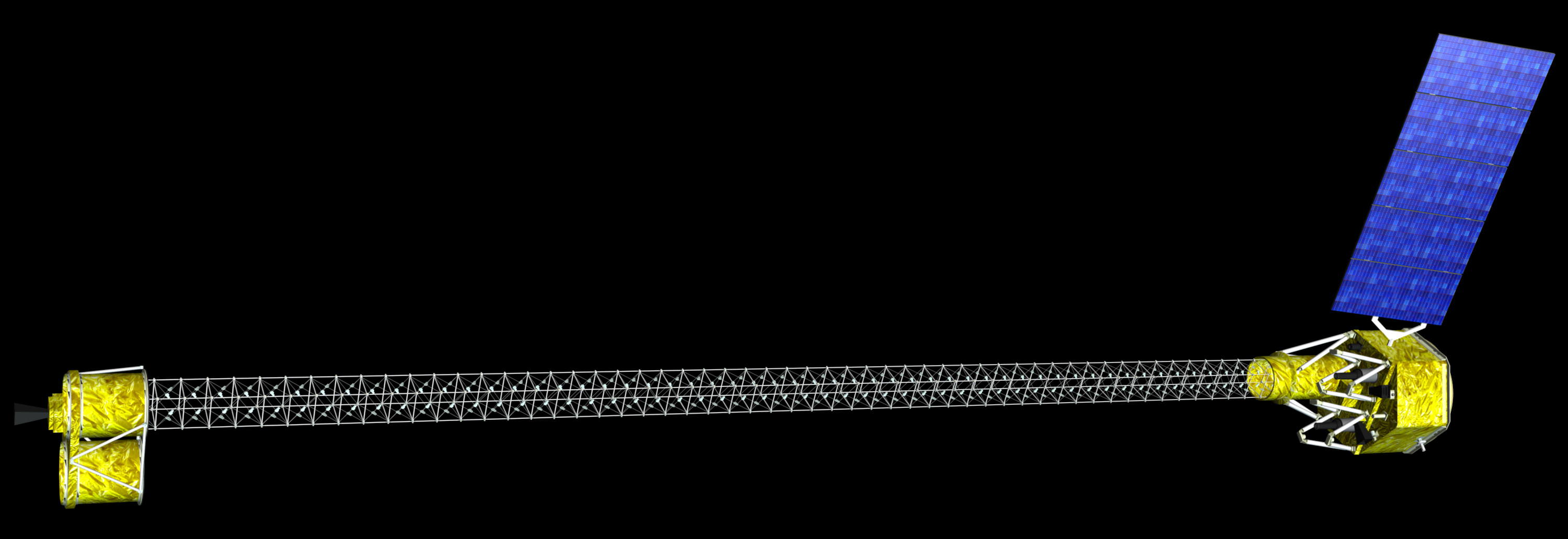

Knight’s proposal, which he calls “Mars on a Shoestring,” outlines two shuttles going into Earth orbit, hooking them together with a truss and strapping on a powerful enough propulsion system. And that’s pretty much it. A pressurized inflatable conduit would connect the two orbiters so the astronauts could go back and forth between the two shuttles.

Then comes the really cool part; a way to provide artificial gravity during the trip to Mars. From Knight’s webpage:

• Once the propulsion stage has accelerated this entire system on its trek to Mars, the truss is detached from the two orbiters and the truss-propulsion assembly is jettisoned.

• The two orbiters then separate to a distance of a few hundred feet, but remain connected — top to top — by a tether cable that is spooled out.

• During the separation, the accordion-style inflatable crew-transfer conduit equally elongates.

• Once the orbiters are at their maximum fixed distance apart, they would simultaneously fire their reaction control systems to set the pair into an elegant pirouette — creating a comfortable level of artificial gravity for the crew’s voyage to the red planet.

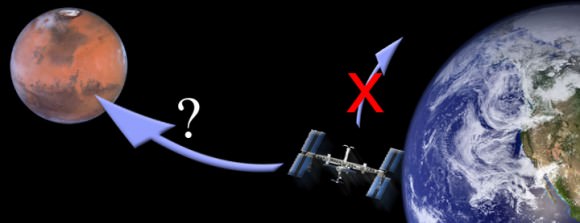

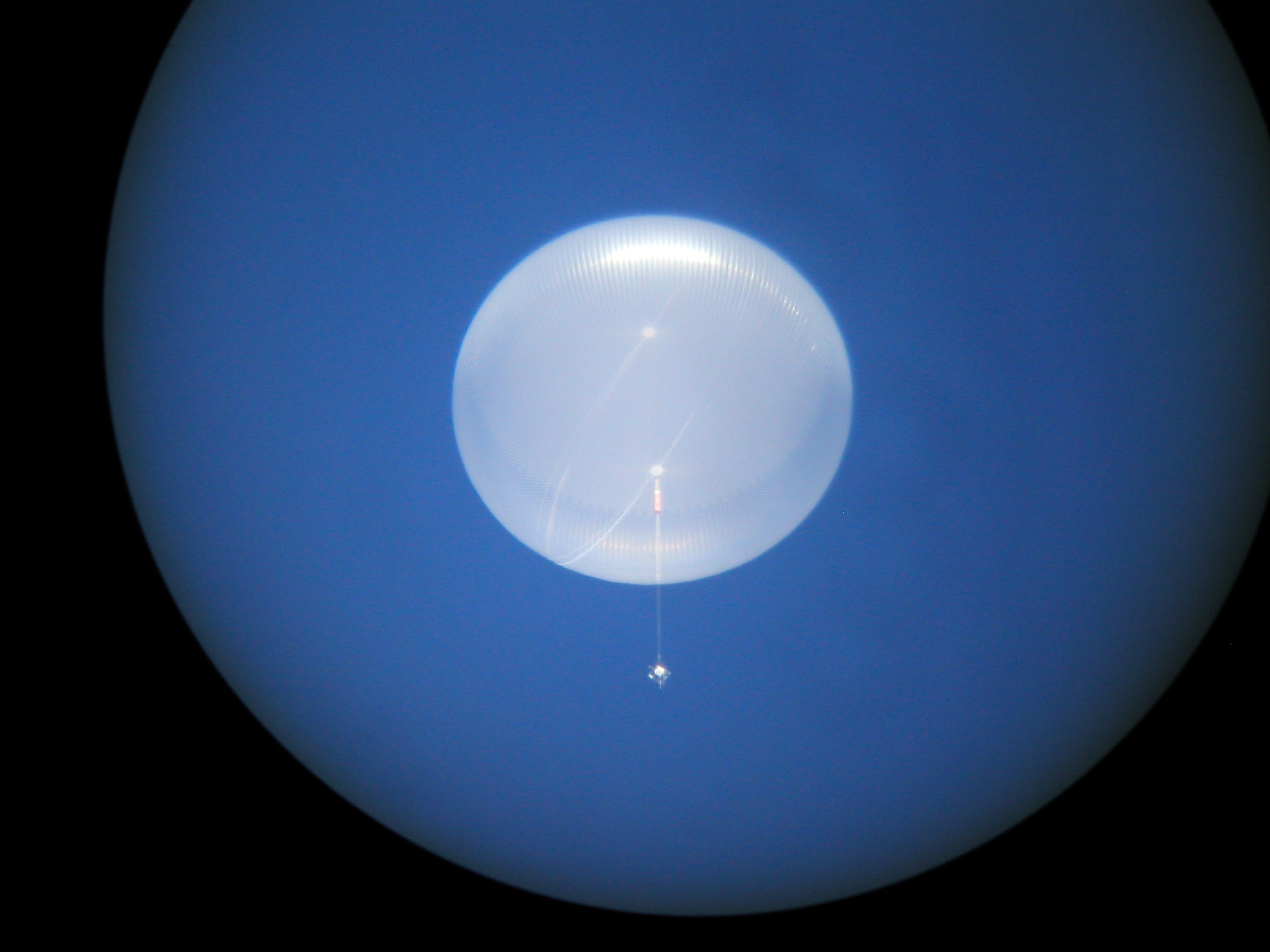

It gets a little dicey once the shuttles arrive at Mars, however. How would these huge spacecrafts get to Mars surface? Knight’s only proposal is separating the orbiters and each having a REALLY huge parachute. Right now, the largest parachute that’s been successfully tested is 150 ft (45 m) in diameter.

However, in an interview we did with JPL’s Rob Manning for a previous article on Universe Today (see “The Mars Landing Approach: Getting Large Payloads to the Surface of the Red Planet), Manning says there’s currently no way and there’s not a parachute big enough to allow a big spacecraft, even a high lift vehicle like a shuttle to land successfully on Mars. The atmosphere is too thin to provide any drag.

From our earlier article:

“Well, on Mars, when you use a very high lift to weight to drag ratio like the shuttle,” said Manning, “in order to get good deceleration and use the lift properly, you’d need to cut low into the atmosphere. You’d still be going at Mach 2 or 3 fairly close to the ground. If you had a good control system you could spread out your deceleration to lengthen the time you are in the air. You’d eventually slow down to under Mach 2 to open a parachute, but you’d be too close to the ground and even an ultra large supersonic parachute would not save you.”

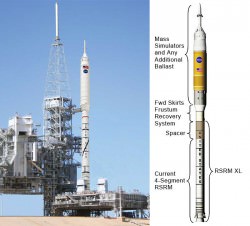

Supersonic parachute experts have concluded that to sufficiently slow a large shuttle-type vehicle on Mars and reach the ground at reasonable speeds would require a parachute one hundred meters in diameter.

“That’s a good fraction of the Rose Bowl. That’s huge,” said Manning. “We believe there’s no way to make a 100-meter parachute that can be opened safely supersonically, not to mention the time it takes to inflate something that large. You’d be on the ground before it was fully inflated. It would not be a good outcome.”

So, while Knight’s proposal is interesting and perhaps forward-thinking, it would need quite a bit of work to actually be feasible. He admits as much, saying “This thought paper is certainly not meant to be the technical be all, end all on the topic — but merely a springboard to new thought. The science and topics touched on herein are superficial; the concepts are simply provided to fuel the imagination and promote discussion.”

Knight said he was inspired by Robert Zubrin’s Mars Direct concept, and he also wanted to “repurpose” the space shuttle fleet.

“In all, I hope that my thought paper provides a catalyst for additional thinking as we ponder our place in the universe — and the methods to transport us to new frontiers.”

Who knows? Many successful endeavors start out as crazy ideas. But first, someone has to have the idea.

Source: Remarkable Technologies