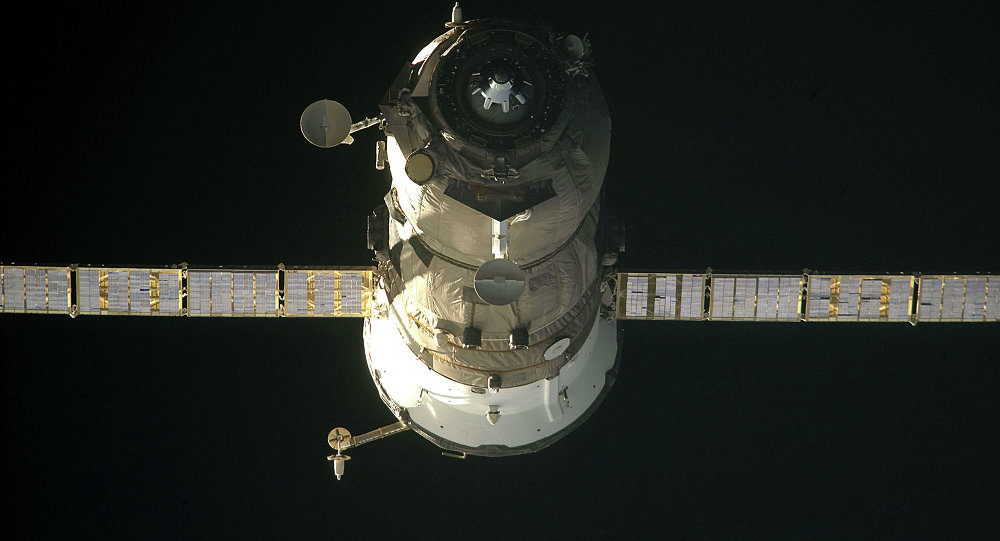

Fourth flight of the secretive U.S. Air Force X-37B Orbital Test Vehicle is set for blastoff on May 20, 2015 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. Photo: Boeing

Story updated with further details and photos[/caption]

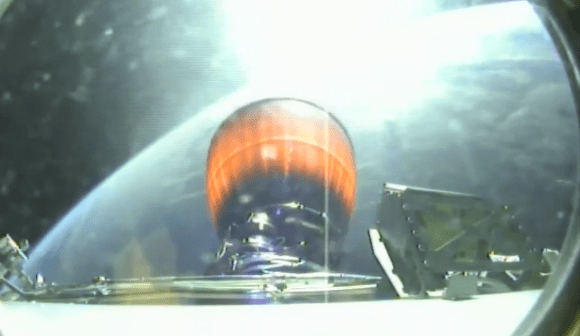

All systems are currently “GO” for the fourth launch of the US Air Force’s secretive unmanned, X-37B military space plane this Wednesday, May 20, on a flight combining both US national security experimental payloads as well as civilian science experiments sponsored by NASA, US Universities, commercial companies, and the solar sailing LightSail test from the Planetary Society.

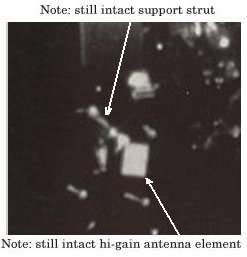

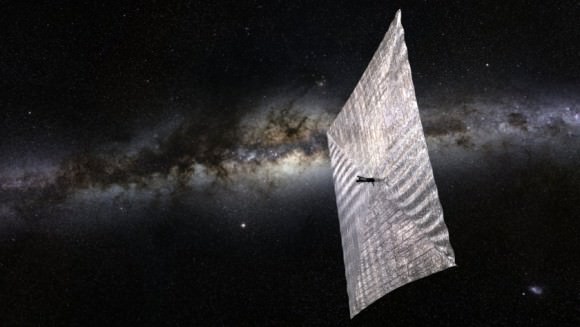

LightSail marks the first controlled, Earth orbit solar sail flight according to the non-profit Planetary Society. It will launch as a separate cubesat experiment. NASA also has an advanced materials science experiment flying aboard the robotically controlled X-37B.

The X-37B is set for blastoff atop a two stage United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V 501 rocket on the AFSPC-5 mission under contract for the U.S. Air Force Rapid Capabilities Office.

The Boeing-built X-37B is an unmanned reusable mini shuttle, also known as the Orbital Test Vehicle (OTV) and is flying on the OTV-4 mission. It launches vertically like a satellite but lands horizontally like an airplane.

Although virtually all the goals of the X-37B program are shrouded in secrecy, some details on the national security objectives have emerged and there are several unclassified experiments flying along as secondary objectives on the rocket and space plane, among them are experiments for NASA and the Planetary Society.

Among the primary mission goals of the first three flights were check outs of the vehicles capabilities and reentry systems and testing the ability to send experiments to space and return them safely. OTV-4 will shift somewhat more to conducting research.

“We are excited about our fourth X-37B mission,” Randy Walden, director of the USAF’s Rapid Capabilities Office, said in a statement. “With the demonstrated success of the first three missions, we’re able to shift our focus from initial checkouts of the vehicle to testing of experimental payloads.”

Liftoff will take place from Space Launch Complex (SLC)-41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida, at some point during a four hour launch period that opens at 10:45 a.m. EDT and extends until 2:45 p.m. EDT on May 20.

ULA announced that the Launch Readiness Review was completed on Monday and everything is progressing normally toward the AFSPC-5 launch. The rocket is fully assembled and the space plane is encapsulated inside the 5 meter diameter payload fairing. It rolled out to the pad today, Tuesday, May 19.

You can watch the Atlas launch live via a ULA webcast here: http://www.ulalaunch.com

The ULA webcast begins at 10:45 a.m. EDT on May 20. The precise launch time is classified and won’t be announced until Wednesday morning.

The weather prognosis has improved markedly to a 60 percent chance of favorable weather conditions, up from only a 40 percent chance this past weekend.

The primary weather concerns are for violations of the launch weather rules related to cumulus clouds, surface electric fields, anvil clouds and lightning.

Launch officials are hopeful that acceptable launch conditions will occur sometime during the lengthy four hour launch window.

In the event of a 24 hour delay due to weather or technical issues, the outlook drops to only a 30% chance of favorable weather conditions during the launch window.

The OTV is somewhat like a miniature version of NASA’s space shuttles. Boeing has built two OTV vehicles.

Altogether the two X-37B vehicles have spent a cumulative total of 1367 days in space during the first three OTV missions and successfully checked out the vehicles reusable flight, reentry and landing technologies.

The reusable space plane is designed to be launched like a satellite and land on a runway like an airplane and a NASA space shuttle. The X-37B is one of the newest and most advanced reentry spacecraft.

The 11,000 pound (4990 kg) state-of -the art reusable OTV space plane was built by Boeing and is about a quarter the size of a NASA space shuttle. It was originally developed by NASA but was transferred to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 2004.

All three OTV missions to date have launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida and landed at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California. Future missions could potentially land at the shuttle landing facility at the Kennedy Space Center, Florida.

The first OTV mission launched on April 22, 2010, and concluded on Dec. 3, 2010, after 224 days in orbit.

The following flights were progressively longer in duration. The second OTV mission began March 5, 2011, and concluded on June 16, 2012, after 468 days on orbit. The third OTV mission launched on Dec. 11, 2012 and landed on Oct. 17, 2014 after 674 days in orbit.

The vehicle measures 29 ft 3 in (8.9 m) in length with a wingspan of 14 ft 11 in (4.5 m). The payload bay measures 7 ft × 4 ft (2.1 m × 1.2 m). The space plane is powered by Gallium Arsenide Solar Cells with Lithium-Ion batteries.

The OTV-4 mission will shift its focus at least somewhat from tests of the vehicles performance to more on science experiments both with extra capacity available on the Atlas V rocket and payload space aboard the X-37B itself.

“We’re very pleased with the experiments lined-up for our fourth OTV Mission OTV-4,” Walden noted.

“We’ll continue to evaluate improvements to the space vehicle’s performance, but we’re honored to host these collaborative experiments that will help advance the state-of-the-art for space technology

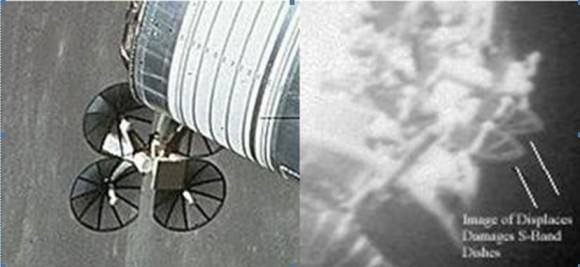

Among the experiments for the flight are 10 CubeSats. They will launch in the Aft Bulkhead Carrier (ABC) located below the Centaur upper stage that contains eight P-Pods to release the CubeSats.

Following primary spacecraft separation the Centaur will change altitude and inclination in order to release the CubeSat spacecraft, ULA said in a statement.

They are sponsored by the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) and NASA and were developed by the U.S. Naval Academy, the Aerospace Corporation, the Air Force Research Laboratory, California Polytechnic State University, and Planetary Society.

NASA is also flying an advanced materials science payload on the X-37B called the Materials Exposure and Technology Innovation in Space (METIS) investigation that will build on more than a decades worth of materials science research on the International Space Station (ISS) research.

“By flying the Materials Exposure and Technology Innovation in Space (METIS) investigation on the X-37B, materials scientists have the opportunity to expose almost 100 different materials samples to the space environment for more than 200 days. METIS is building on data acquired during the Materials on International Space Station Experiment (MISSE), which flew more than 4,000 samples in space from 2001 to 2013, NASA said in a statement.

“By exposing materials to space and returning the samples to Earth, we gain valuable data about how the materials hold up in the environment in which they will have to operate,” said Miria Finckenor, the co-investigator on the MISSE experiment and principal investigator for METIS at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

“Spacecraft designers can use this information to choose the best material for specific applications, such as thermal protection or antennas or any other space hardware.”

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.