[/caption]

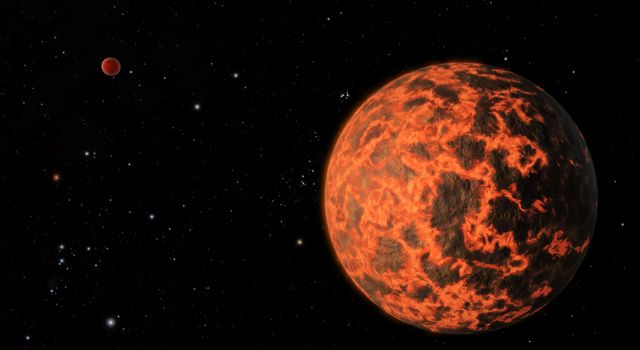

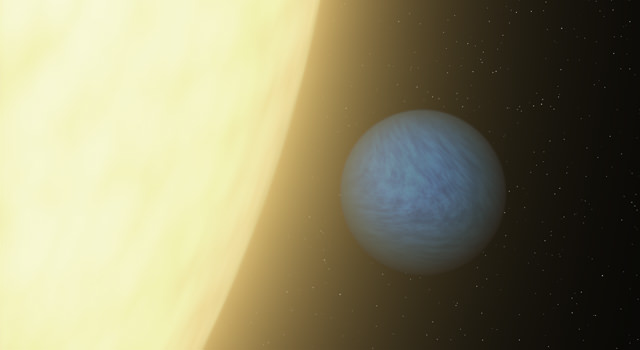

The star 55 Cancri has been a source of joy and firsts for planet hunters. Not only was it one of the first known stars to host an extrasolar planet, but now the light from one of its five known planets has been detected directly with the Spitzer Space Telescope, the first time a ‘smaller’ exoplanet’s light has been detected directly. Planet “e” is a super-Earth, about twice as big and eight times as massive as Earth. Scientists say that while the planet is not habitable, the detection is a historic step toward the eventual search for signs of life on other planets.

“Spitzer has amazed us yet again,” said Bill Danchi, Spitzer program scientist. “The spacecraft is pioneering the study of atmospheres of distant planets and paving the way for NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope to apply a similar technique on potentially habitable planets.”

The first planet around 55 Cancri was reported in 1997 and 55 Cancri e – the innermost planet in the system — was discovered via radial velocity measurements in 2004. This planet has been studied as much as possible, and astronomers were able to determine its mass and radius.

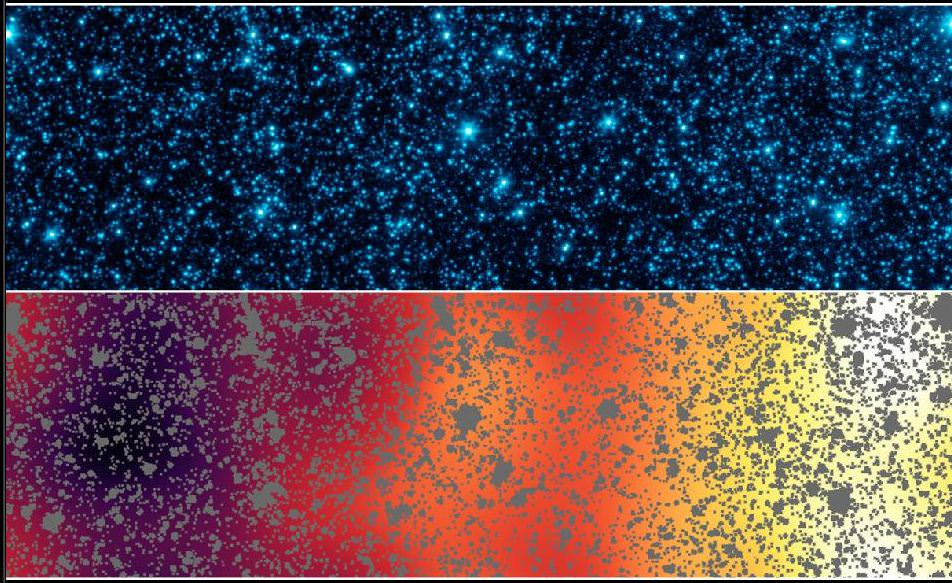

But now, Spitzer has measured how much infrared light comes from the planet itself. The results reveal the planet is likely dark, and its sun-facing side is more than 2,000 Kelvin (1,726 degrees Celsius, 3,140 degrees Fahrenheit), hot enough to melt metal.

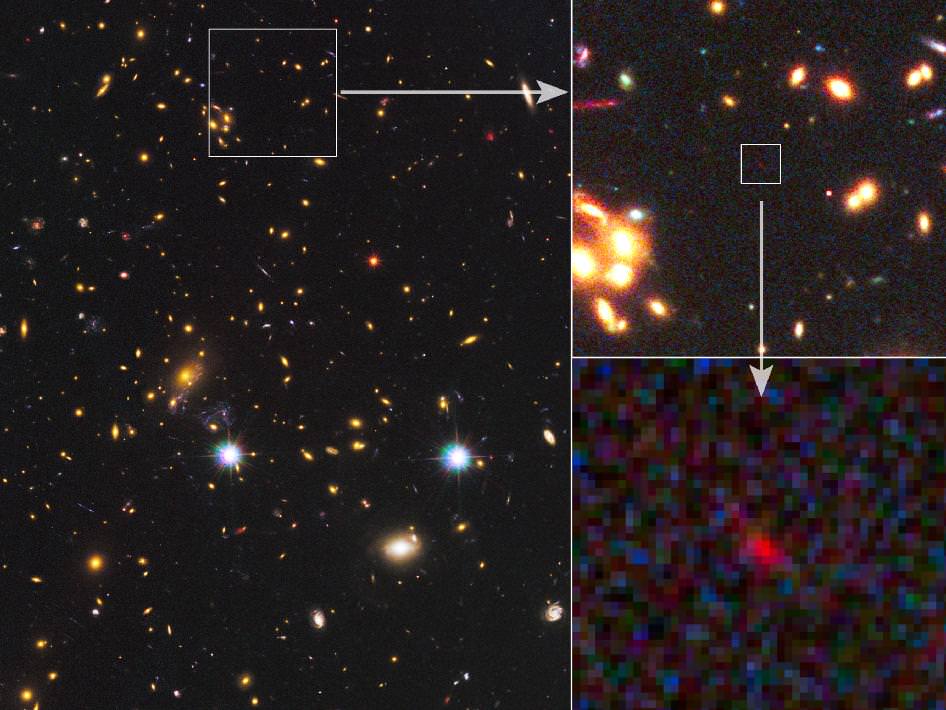

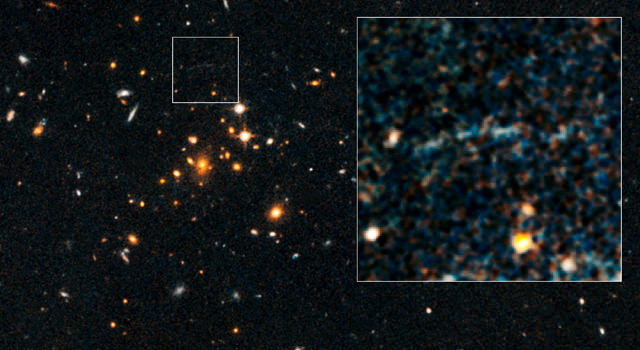

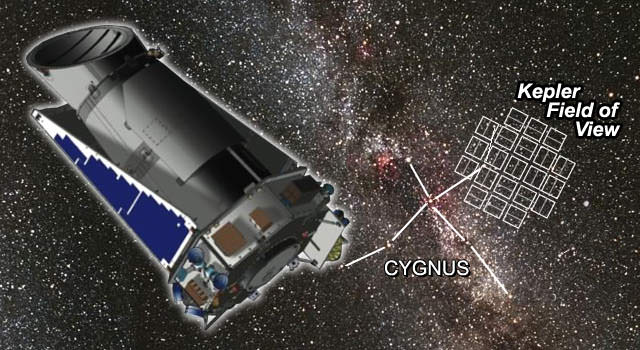

In 2005, Spitzer became the first telescope to detect light from a planet beyond our solar system, when it saw the infrared light of a “hot Jupiter,” a gaseous planet much larger than 55 Cancri e. Since then, other telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble and Kepler space telescopes, have performed similar feats with gas giants using the same method.

In this method, a telescope gazes at a star as a planet circles behind it. When the planet disappears from view, the light from the star system dips ever so slightly, but enough that astronomers can determine how much light came from the planet itself. This information reveals the temperature of a planet, and, in some cases, its atmospheric components. Most other current planet-hunting methods obtain indirect measurements of a planet by observing its effects on the star.

The new information about 55 Cancri e, along with knowing it is about 8.57 Earth masses, the radius is 1.63 times that of Earth, and the density is 10.9 ± 3.1 g cm-3 (the average density of Earth is 5.515 g cm-3), places the planet firmly into the categories of a rocky super-Earth. But it could be surrounded by a layer of water in a “supercritical” state where it is both liquid and gas, and topped by a blanket of steam.

“It could be very similar to Neptune, if you pulled Neptune in toward our sun and watched its atmosphere boil away,” said Michaël Gillon of Université de Liège in Belgium, principal investigator of the research, which appears in the Astrophysical Journal. The lead author is Brice-Olivier Demory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge.

The 55 Cancri system is relatively close to Earth, at 41 light-years away, and the star can be seen with the naked eye. 55 Cancri e is tidally locked, so one side always faces the star. Spitzer discovered the sun-facing side is extremely hot, indicating the planet probably does not have a substantial atmosphere to carry the sun’s heat to the unlit side.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled to launch in 2018, likely will be able to learn even more about the planet’s composition. The telescope might be able to use a similar infrared method to Spitzer to search other potentially habitable planets for signs of molecules possibly related to life.

“When we conceived of Spitzer more than 40 years ago, exoplanets hadn’t even been discovered,” said Michael Werner, Spitzer project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “Because Spitzer was built very well, it’s been able to adapt to this new field and make historic advances such as this.”

During Spitzer’s ongoing extended mission, steps were taken to enhance its unique ability to see exoplanets, including 55 Cancri e. Those steps, which included changing the cycling of a heater and using an instrument in a new way, led to improvements in how precisely the telescope points at targets.

Source: JPL