[/caption]

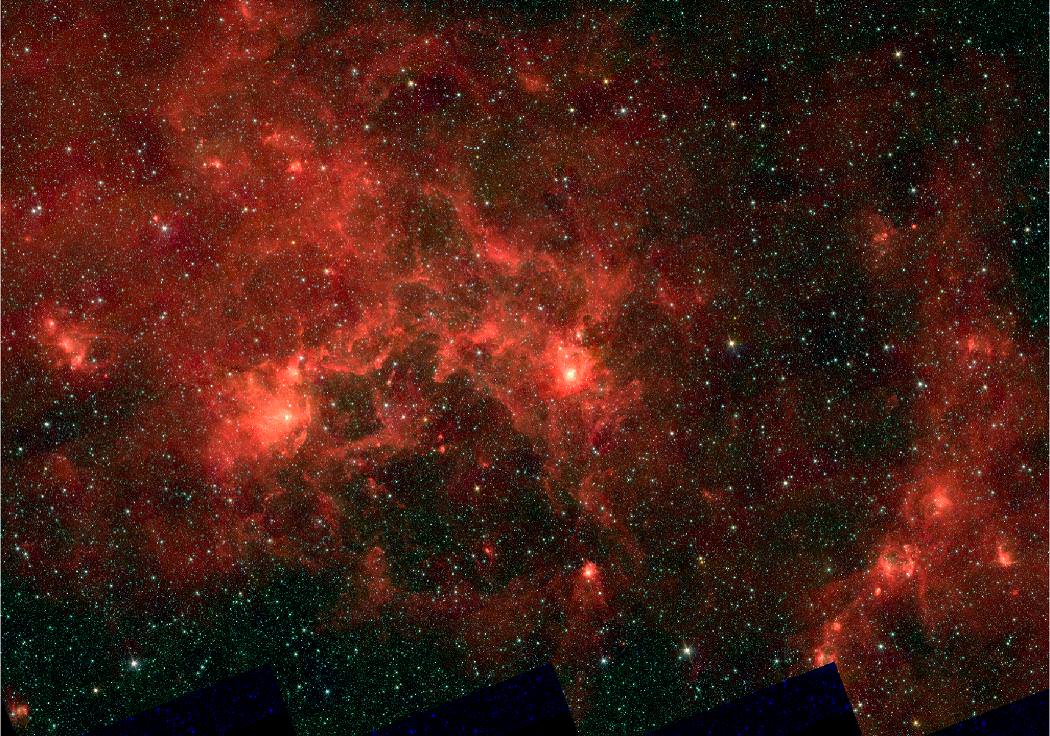

Astronomers using data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope have, for the first time, discovered buckyballs in a solid form in space. Prior to this discovery, the microscopic carbon spheres had been found only in gas form in the cosmos. The new work, led by Prof. Nye Evans of Keele University, appears in a paper in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

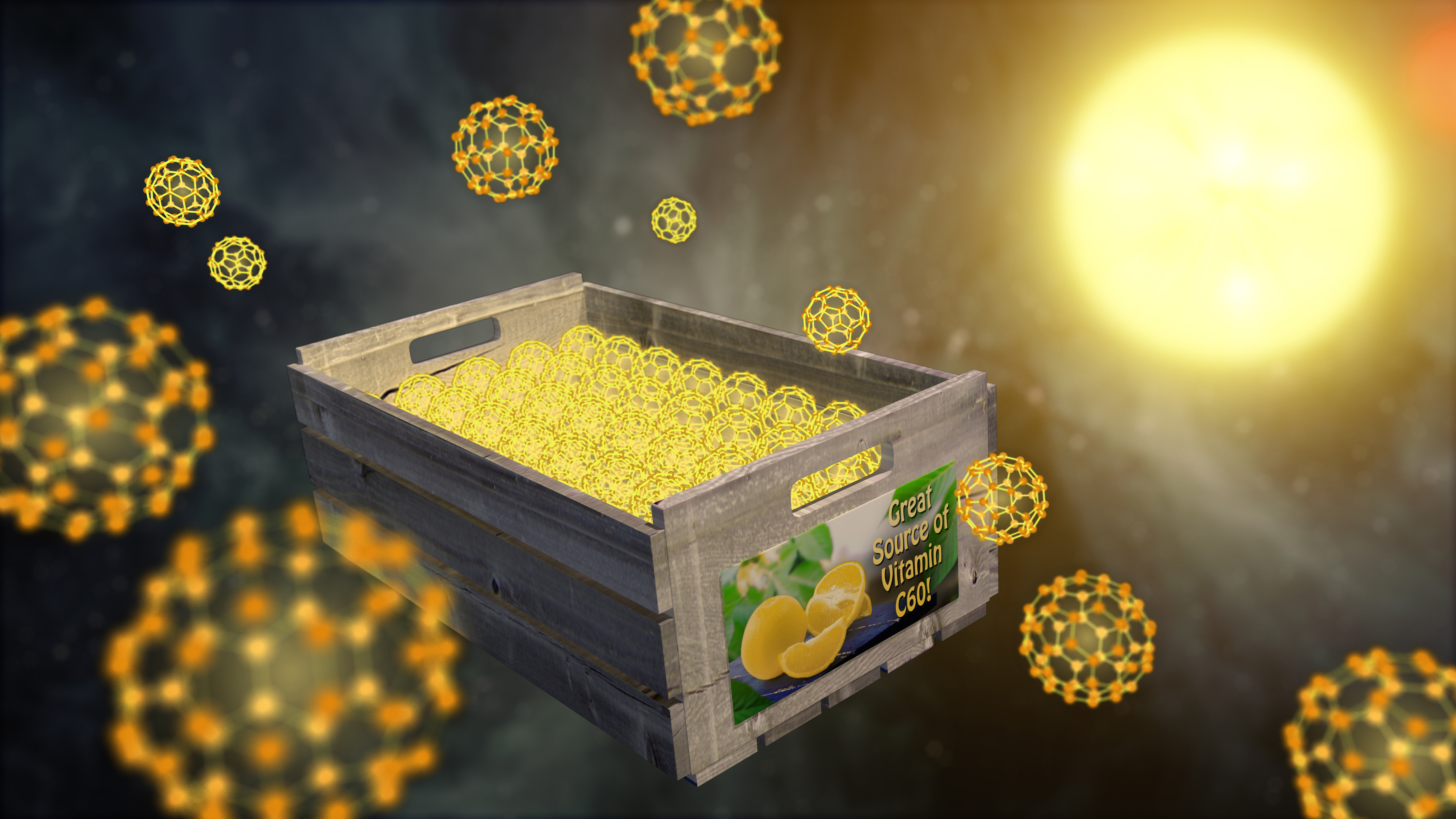

Formally named buckminsterfullerene, buckyballs are named after their resemblance to the late architect Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes. They are made up of 60 carbon molecules arranged into a hollow sphere like a football. Their unusual structure makes them ideal candidates for electrical and chemical applications on Earth, including superconducting materials, medicines, water purification and armour.

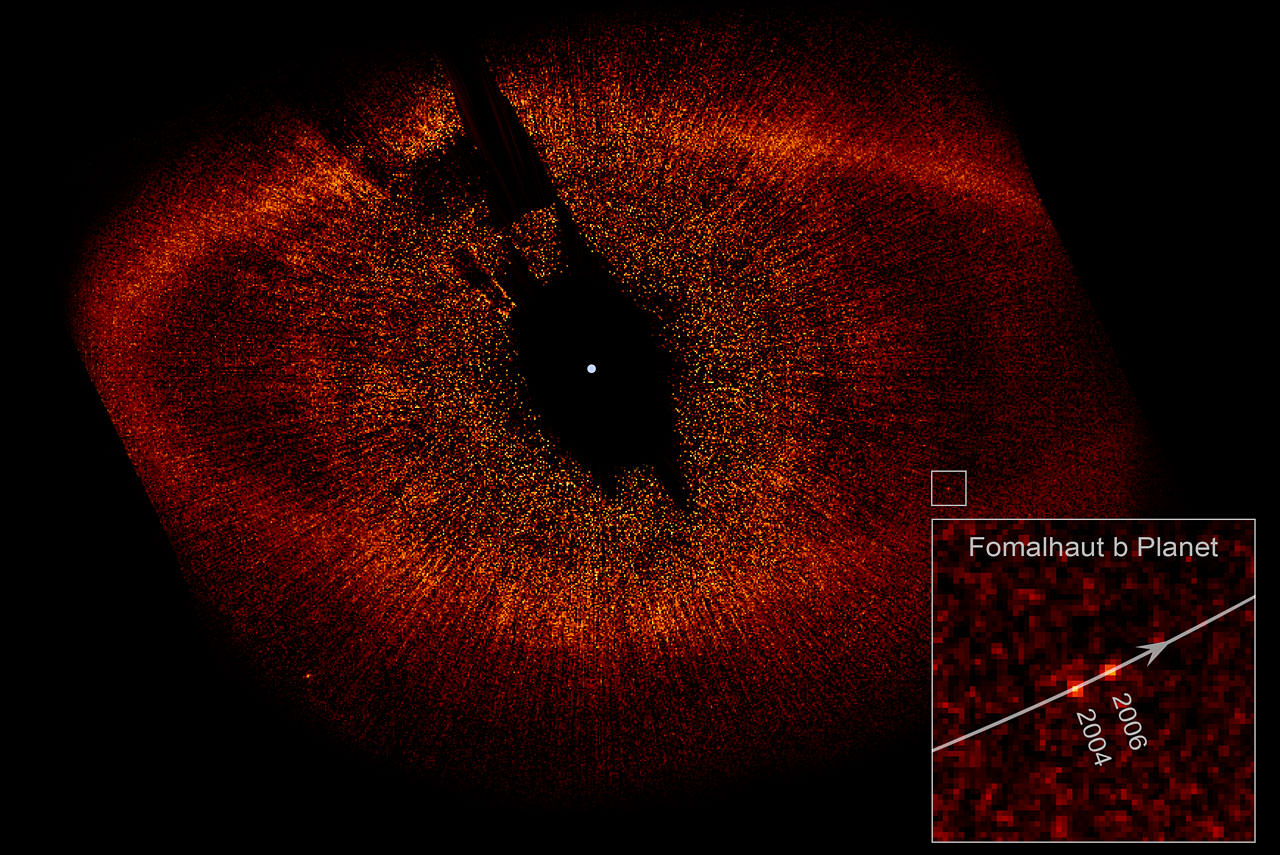

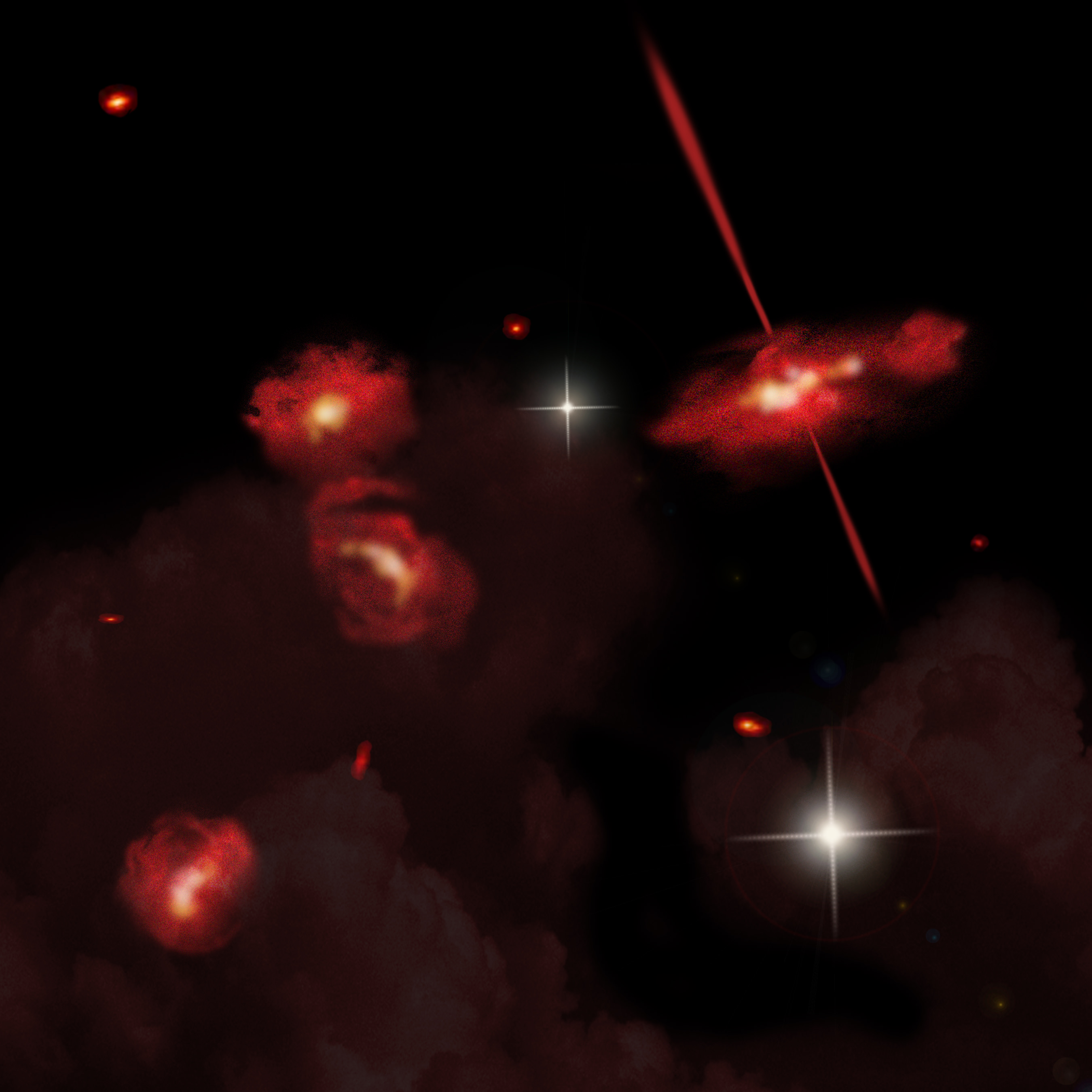

In the latest discovery, scientists using Spitzer detected tiny specks of matter, or particles, consisting of stacked buckyballs. They found the particles around a pair of stars called “XX Ophiuchi,” 6,500 light-years from Earth, and detected enough to fill the equivalent in volume to 10,000 Mount Everests.

“These buckyballs are stacked together to form a solid, like oranges in a crate,” said Prof. Evans. “The particles we detected are miniscule, far smaller than the width of a hair, but each one would contain stacks of millions of buckyballs.”

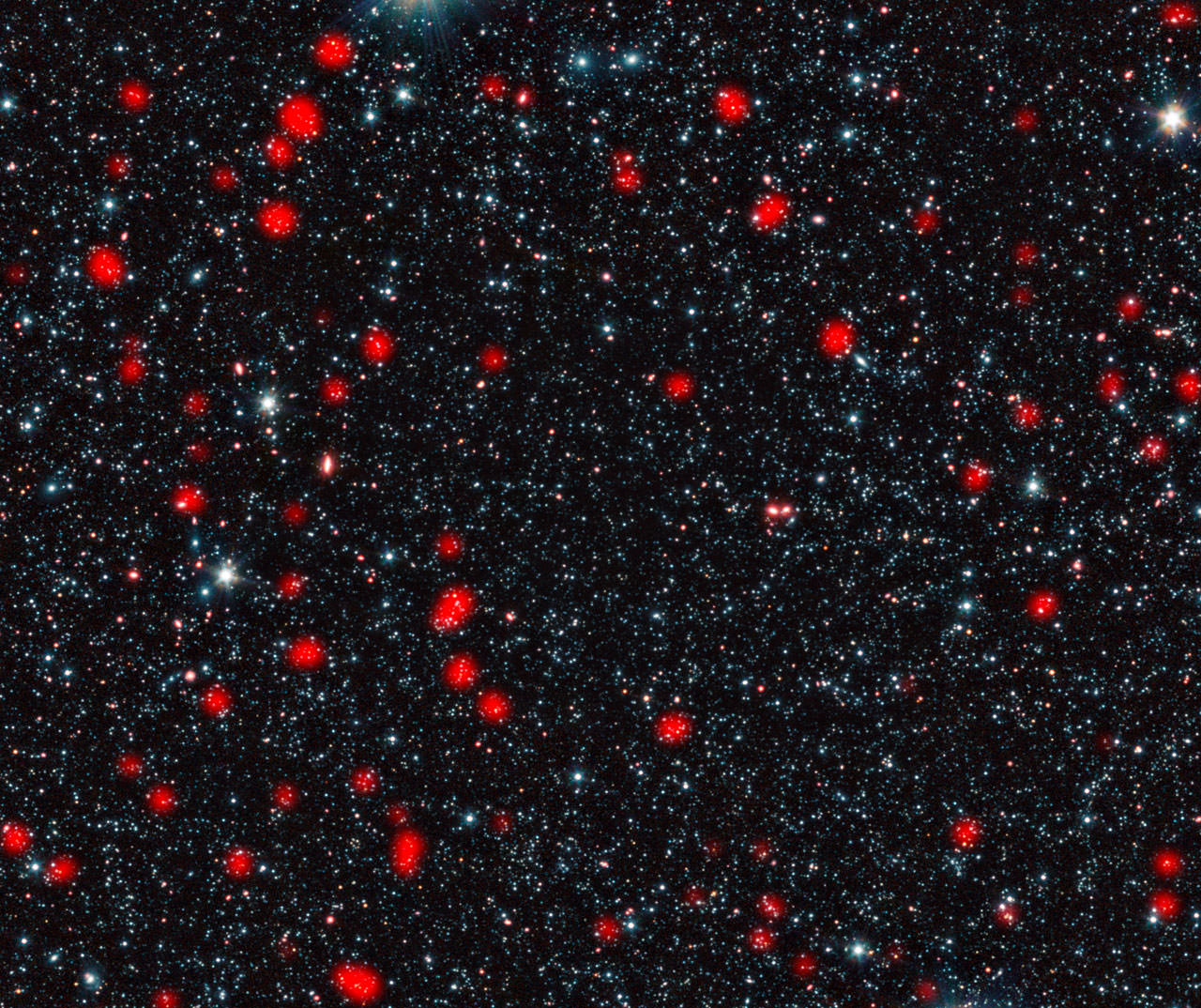

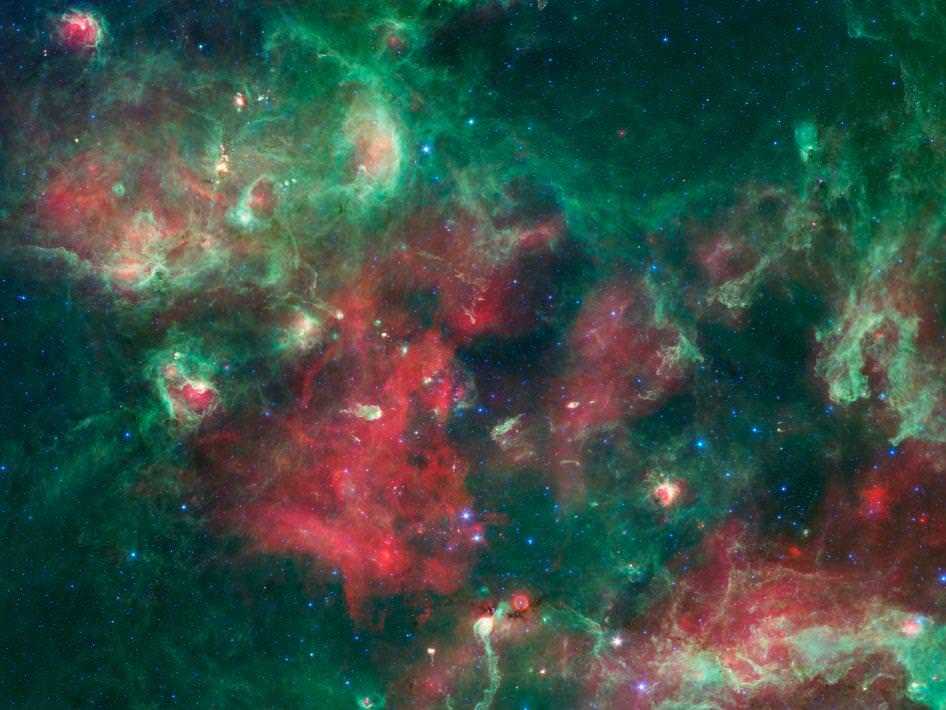

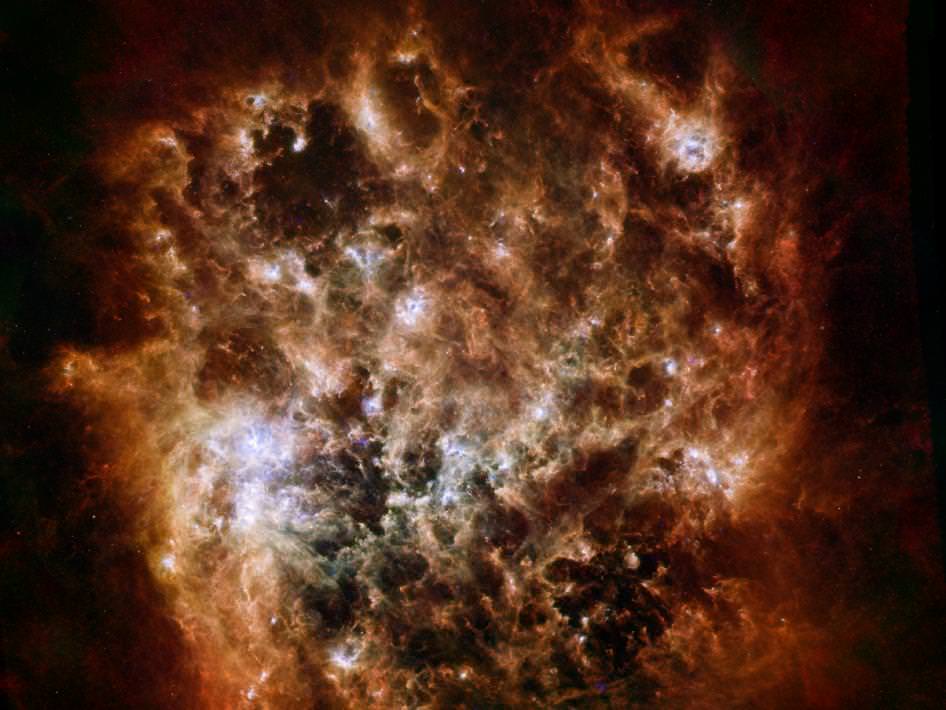

Buckyballs were detected definitively in space for the first time by Spitzer in 2010. Spitzer later identified the molecules in a host of different cosmic environments. It even found them in staggering quantities, the equivalent in mass to 15 Earth moons, in a nearby galaxy called the Small Magellanic Cloud.

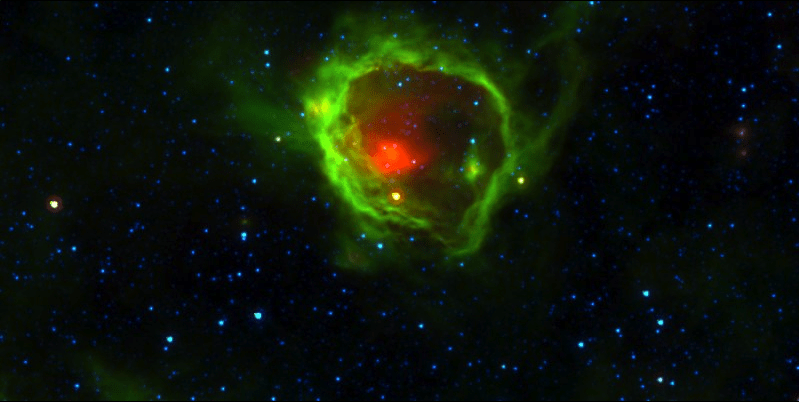

In all of those cases, the molecules were in the form of gas. The recent discovery of buckyballs particles means that large quantities of these molecules must be present in some stellar environments in order to link up and form solid particles. The research team was able to identify the solid form of buckyballs in the Spitzer data because they emit light in a unique way that differs from the gaseous form.

“This exciting result suggests that buckyballs are even more widespread in space than the earlier Spitzer results showed,” said Mike Werner, project scientist for Spitzer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “They may be an important form of carbon, an essential building block for life, throughout the cosmos.”

Buckyballs have been found on Earth in various forms. They form as a gas from burning candles and exist as solids in certain types of rock, such as the mineral shungite found in Russia, and fulgurite, a glassy rock from Colorado that forms when lightning strikes the ground. In a test tube, the solids take on the form of dark, brown “goo.”

“The window Spitzer provides into the infrared universe has revealed beautiful structure on a cosmic scale,” said Bill Danchi, Spitzer program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “In yet another surprise discovery from the mission, we’re lucky enough to see elegant structure at one of the smallest scales, teaching us about the internal architecture of existence.”