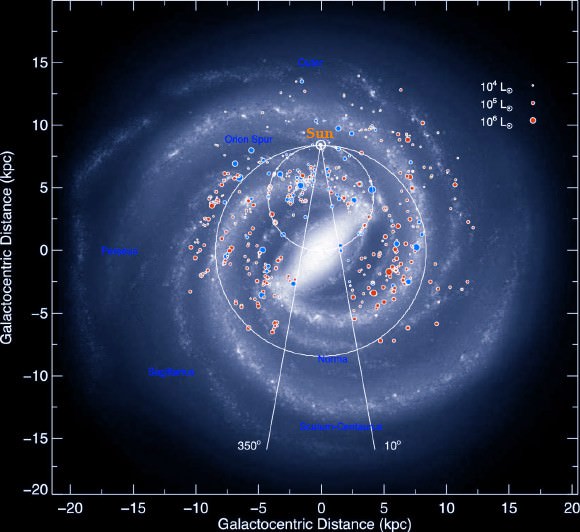

Astronomers have been arguing over just how many spiral arms our Galaxy exhibits. Is the Milky Way a four or two-armed spiral galaxy? Astronomers had often assumed the Milky Way was potentially a four-armed spiral galaxy, but comparatively recent observations from NASA’s Spitzer telescope implied the Galaxy had two spiral arms. In 2013, astronomers mapped star forming regions and argued they had found the two missing arms, bringing the total number of arms back to four.

The case for a four-armed Milky Way may have just gotten stronger.

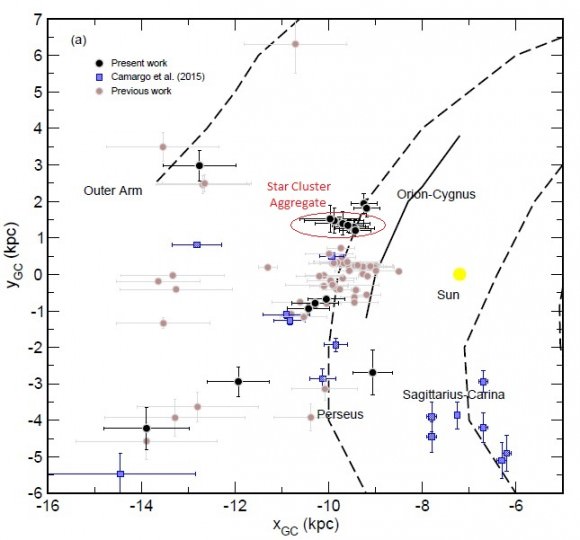

A team of Brazilian astronomers used star clusters embedded in their natal clouds to trace the Galaxy’s structure. “Our results favour a four-armed spiral Galaxy, which includes the Sagittarius-Carina, Perseus, and Outer arms.”, remarked the group from the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul.

“Despite efforts aimed at improving our understanding of the Galaxy’s structure, questions remain. There is no consensus regarding the number and shape of the Galaxy’s spiral arms.”, noted lead author D. Camargo. He added that the Sun’s location within the obscured disc of the Galaxy was a principal factor hindering our understanding of the Milky Way’s broader structure. In other words, we do not have a bird’s eye view of our Galaxy.

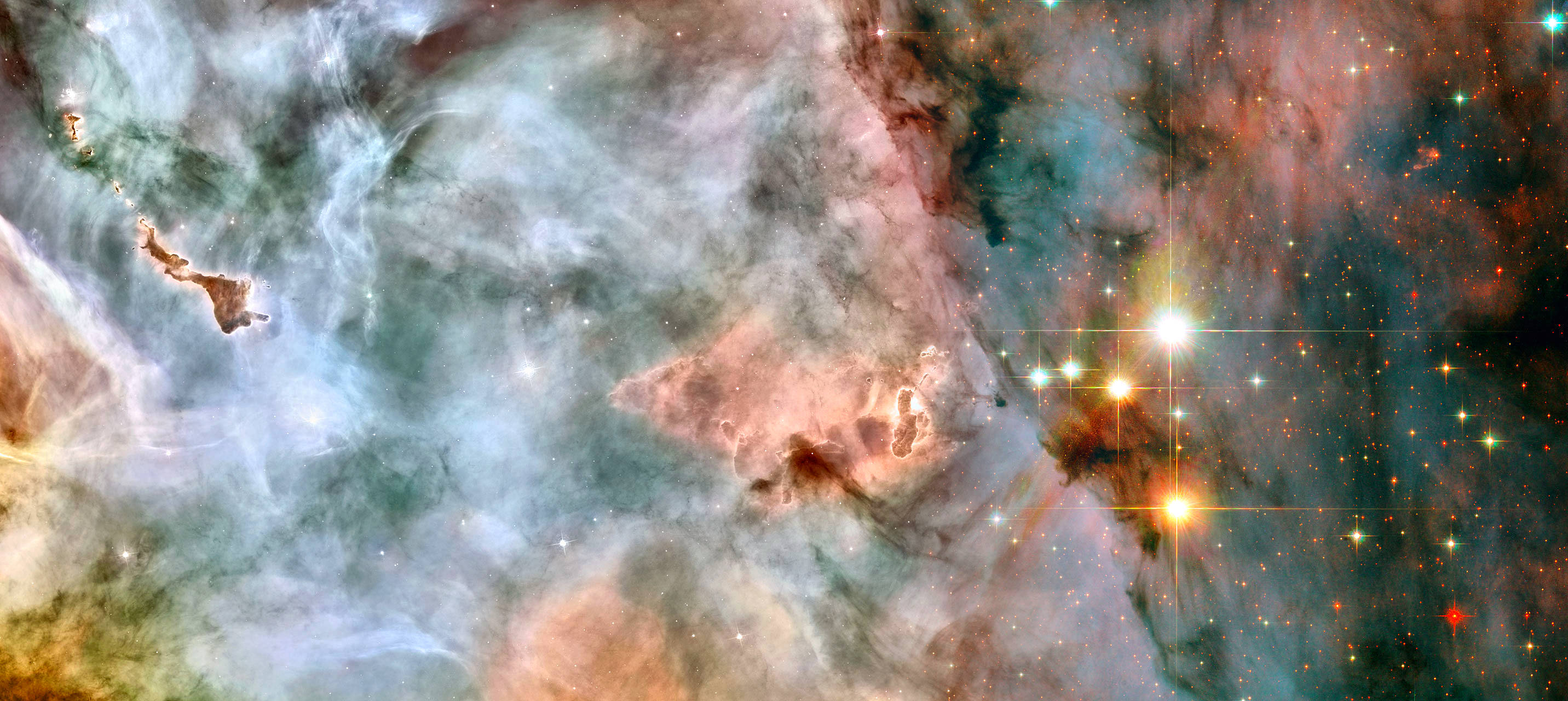

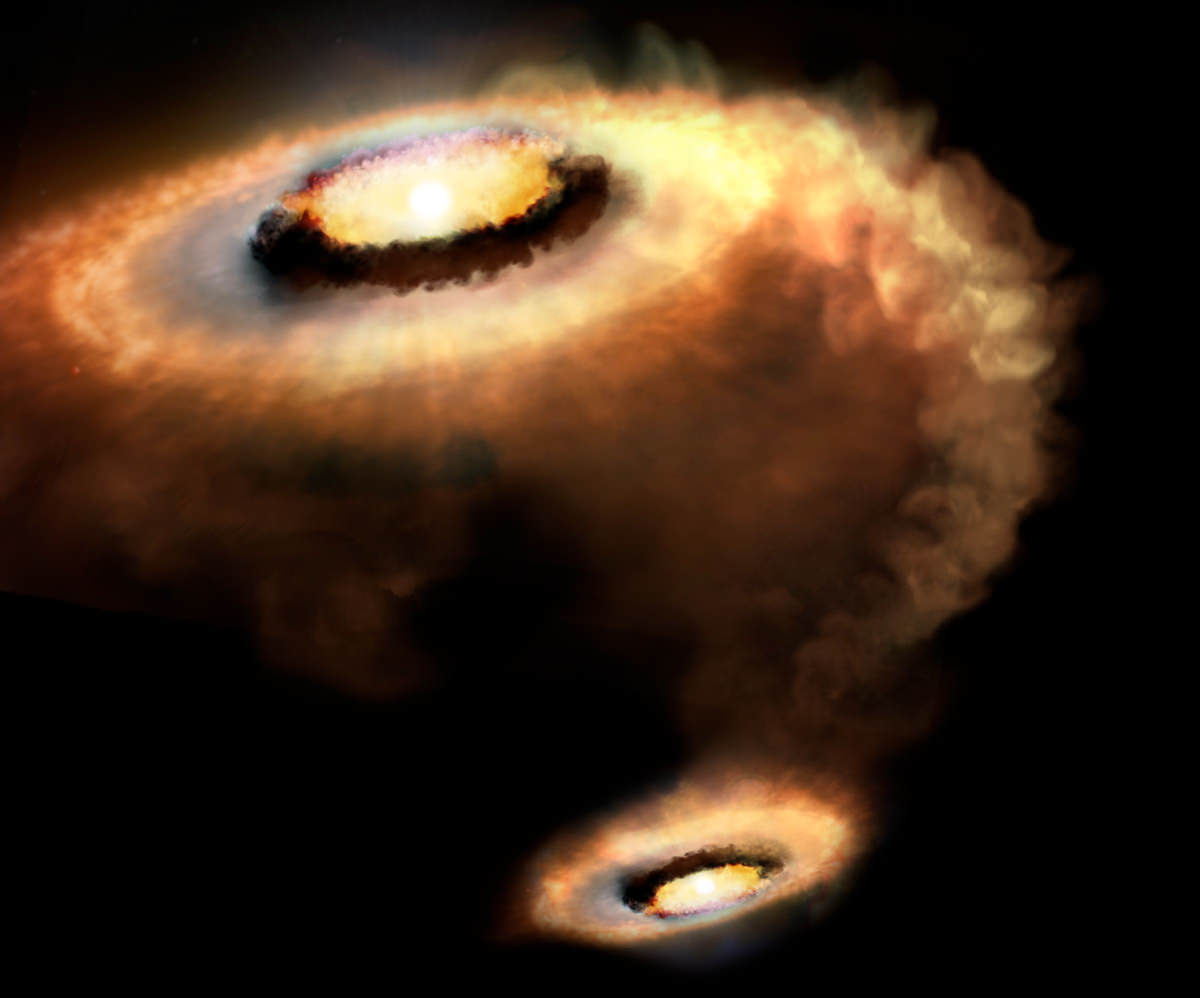

The team remarked that young embedded clusters are excellent tracers of the Galaxy’s structure, “The present results indicate that the Galaxy’s embedded clusters are predominantly located in the spiral arms.” They noted that star formation may occur after the collapse and fragmentation of giant molecular clouds found within spiral arms, and consequently the young embedded star clusters that subsequently emerge are excellent probes of Galactic structure as they have not displaced far from their birthplace.

The team used data from NASA’s WISE infrared telescope to identify young clusters still embedded in their natal clouds, which are often encompassed by significant dust. Infrared stellar light is less obscured by dust than visible light, giving the astronomers an unprecedented view. Indeed, the group discovered 7 new embedded clusters, several of which (designated Camargo 441-444) may belong to a larger aggregate that resides in the Perseus arm. They suggested that a giant molecular cloud was compressed by the spiral arm which may have triggered star formation in several clumps, and numerous star clusters with similar ages emerged (an alternative or concurrent scenario is sequential formation).

Astronomer A. Mainzer discusses NASA’s WISE telescope (Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer), which was used by Camargo et al. 2015 to identify embedded star clusters.

The team also used near-infrared data from the 2MASS survey to determine distances for the star clusters, once the objects were identified in the WISE images. A primary goal of their work was to establish accurate fundamental cluster parameters, which would bolster any resulting conclusions concerning the Galaxy’s overall structure. An innovative algorithm was therefore adopted to minimize contamination by foreground and background stars along the sight-line, which may otherwise appear as cluster members and degrade the reliability of any distant estimates.

“The embedded clusters in the present sample are distributed along the Sagittarius-Carina, Perseus, and Outer arms.”, concluded the team. They likewise noted that the search for new embedded clusters throughout the entire Galaxy must continue unabated, since such targets may foster our understanding of the Galaxy’s structure.

The discoveries are described in a new study by D. Camargo, C. Bonatto, and E. Bica that is entitled “Tracing the Galactic spiral structure with embedded clusters”. The research has been accepted for publication, and will appear in a forthcoming issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MNRAS). A preprint of the work is available on arXiv.