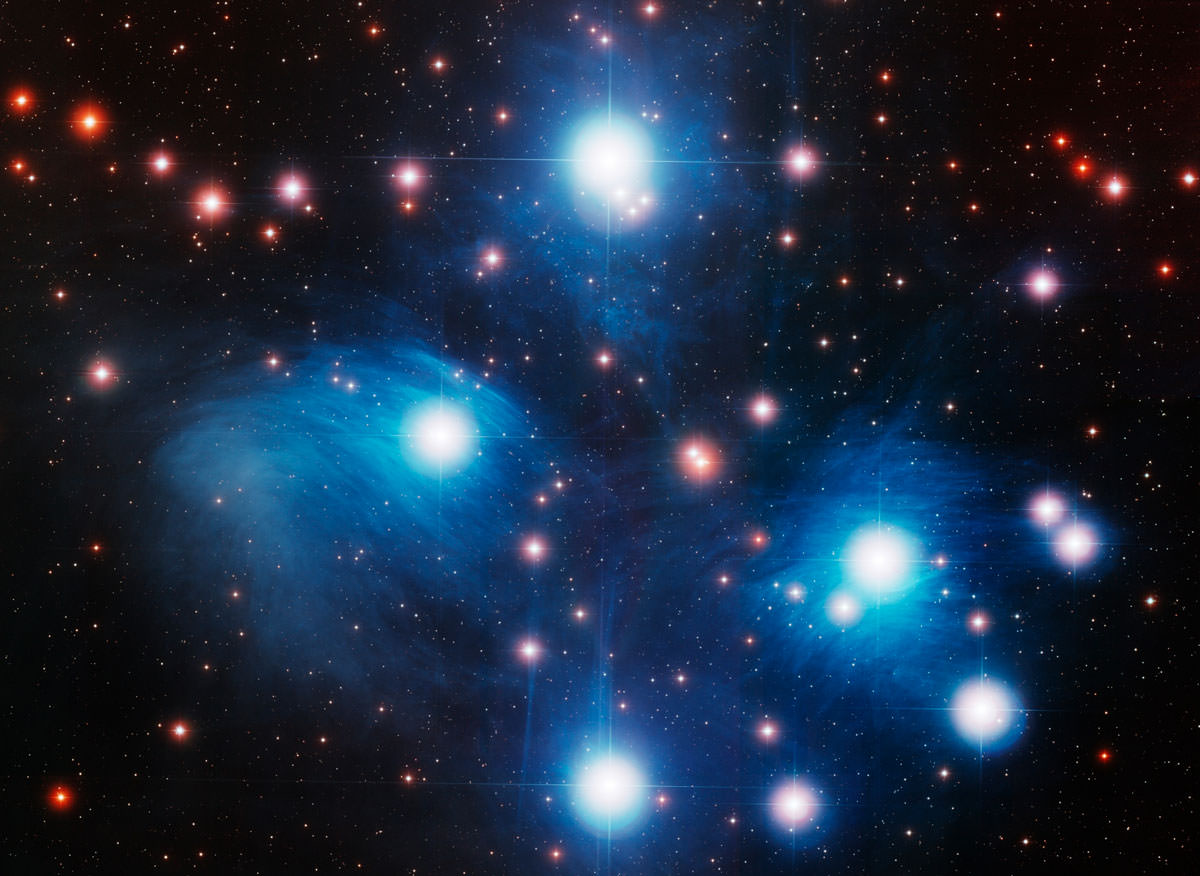

Fall will soon be at our doorstep. But before the leaves change colors and the smell of pumpkin fills our coffee shops, the Pleiades star cluster will mark the new season with its earlier presence in the night sky.

The delicate grouping of blue stars has been a prominent sight since antiquity. But in recent years, the cluster has also been the subject of an intense debate, marking a controversy that has troubled astronomers for more than a decade.

Now, a new measurement argues that the distance to the Pleiades star cluster measured by ESA’s Hipparcos satellite is decidedly wrong and that previous measurements from ground-based telescopes had it right all along.

The Pleiades star cluster is a perfect laboratory to study stellar evolution. Born from the same cloud of gas, all stars exhibit nearly identical ages and compositions, but vary in their mass. Accurate models, however, depend greatly on distance. So it’s critical that astronomers know the cluster’s distance precisely.

A well pinned down distance is also a perfect stepping stone in the cosmic distance ladder. In other words, accurate distances to the Pleiades will help produce accurate distances to the farthest galaxies.

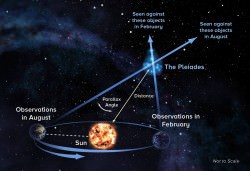

But accurately measuring the vast distances in space is tricky. A star’s trigonometric parallax — its tiny apparent shift against background stars caused by our moving vantage point — tells its distance more truly than any other method.

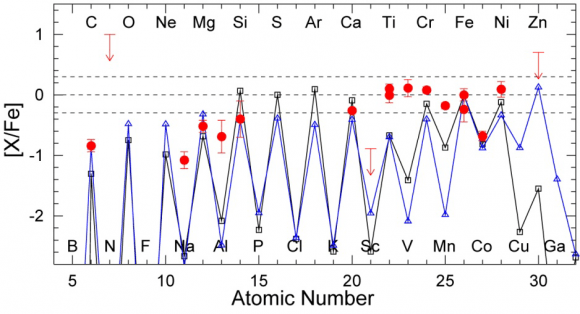

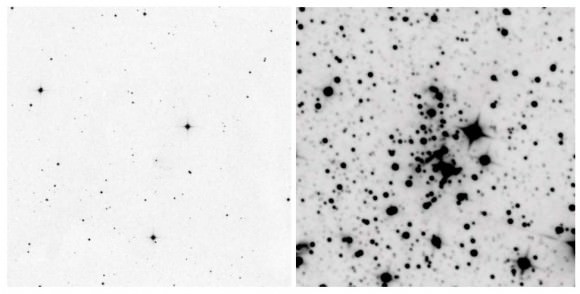

Originally the consensus was that the Pleiades are about 435 light-years from Earth. However, ESA’s Hipparcos satellite, launched in 1989 to precisely measure the positions and distances of thousands of stars using parallax, produced a distance measurement of only about 392 light-years, with an error of less than 1%.

“That may not seem like a huge difference, but, in order to fit the physical characteristics of the Pleiades stars, it challenged our general understanding of how stars form and evolve,” said lead author Carl Melis, of the University of California, San Diego, in a press release. “To fit the Hipparcos distance measurement, some astronomers even suggested that some type of new and unknown physics had to be at work in such young stars.”

If the cluster really was 10% closer than everyone had thought, then the stars must be intrinsically dimmer than stellar models suggested. A debate ensued as to whether the spacecraft or the models were at fault.

To solve the discrepancy, Melis and his colleagues used a new technique known as very-long-baseline radio interferometry. By linking distant telescopes together, astronomers generate a virtual telescope, with a data-gathering surface as large as the distances between the telescopes.

The network included the Very Long Baseline Array (a system of 10 radio telescopes ranging from Hawaii to the Virgin Islands), the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, the William E. Gordon Telescope at the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, and the Effelsberg Radio Telescope in Germany.

“Using these telescopes working together, we had the equivalent of a telescope the size of the Earth,” said Amy Miouduszewski, of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO). “That gave us the ability to make extremely accurate position measurements — the equivalent of measuring the thickness of a quarter in Los Angeles as seen from New York.”

After a year and a half of observations, the team determined a distance of 444.0 light-years to within 1% — matching the results from previous ground-based observations and not the Hipparcos satellite.

“The question now is what happened to Hipparcos?” Melis said.

The spacecraft measured the position of roughly 120,000 nearby stars and — in principle — calculated distances that were far more precise than possible with ground-based telescopes. If this result holds up, astronomers will grapple with why the Hipparcos observations misjudged the distances so badly.

ESA’s long-awaited Gaia observatory, which launched on Dec. 19, 2013, will use similar technology to measure the distances of about one billion stars. Although it’s now ready to begin its science mission, the mission team will have to take special care, utilizing the work of ground-based radio telescopes in order to ensure their measurements are accurate.

The findings have been published in the Aug. 29 issue of Science and is available online.