Even though it comprises over 99% of the mass of the Solar System (with Jupiter taking up most of the rest) our Sun is, in terms of the entire Milky Way, a fairly average star. There are lots of less massive stars than the Sun out there in the galaxy, as well as some real stellar monsters… and based on new observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, there’s about to be one more.

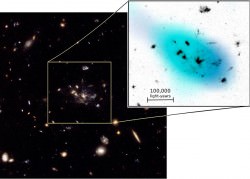

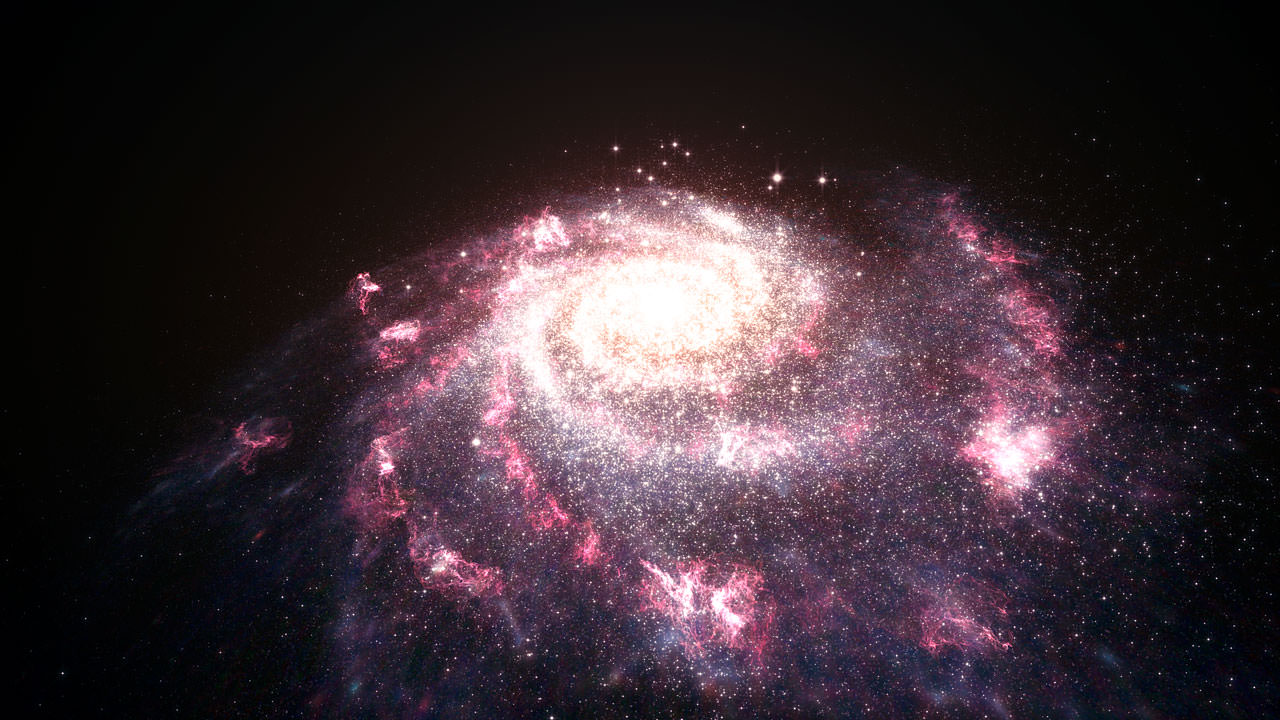

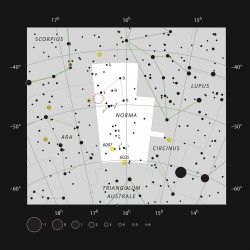

Early science observations with ALMA have provided astronomers with the best view yet of a monster star in the process of forming within a dark cloud of dust and gas. Located 11,000 light-years away, Spitzer Dark Cloud 335.579-0.292 is a stellar womb containing over 500 times the mass of the Sun — and it’s still growing. Inside this cloud is an embryonic star hungrily feeding on inwardly-flowing material, and when it’s born it’s expected to be at least 100 times the mass of our Sun… a true stellar monster.

The star-forming region is the largest ever found in our galaxy.

“The remarkable observations from ALMA allowed us to get the first really in-depth look at what was going on within this cloud,” said Nicolas Peretto of CEA/AIM Paris-Saclay, France, and Cardiff University, UK. “We wanted to see how monster stars form and grow, and we certainly achieved our aim! One of the sources we have found is an absolute giant — the largest protostellar core ever spotted in the Milky Way.”

Watch: What’s the Biggest Star in the Universe?

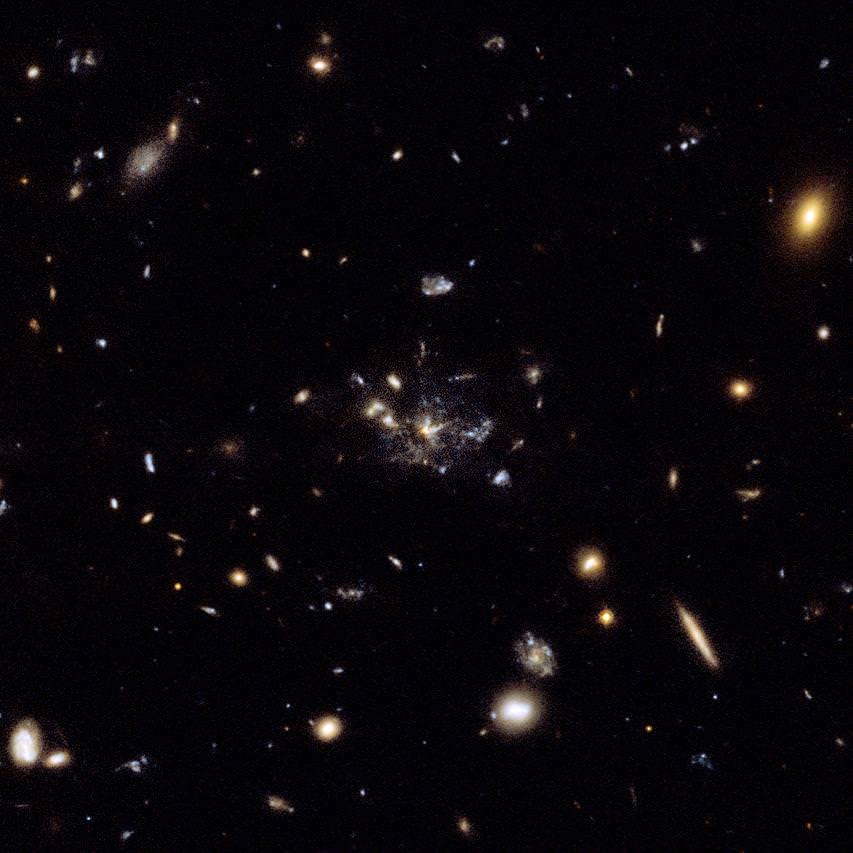

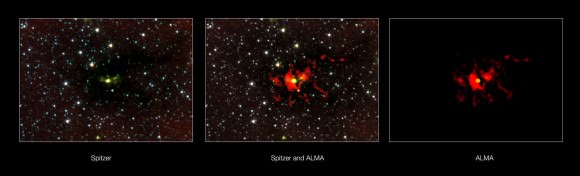

SDC 335.579-0.292 had already been identified with NASA’s Spitzer and ESA’s Herschel space telescopes, but it took the unique sensitivity of ALMA to observe in detail both the amount of dust present and the motion of the gas within the dark cloud, revealing the massive embryonic star inside.

“Not only are these stars rare, but their birth is extremely rapid and their childhood is short, so finding such a massive object so early in its evolution is a spectacular result.”

– Team member Gary Fuller, University of Manchester, UK

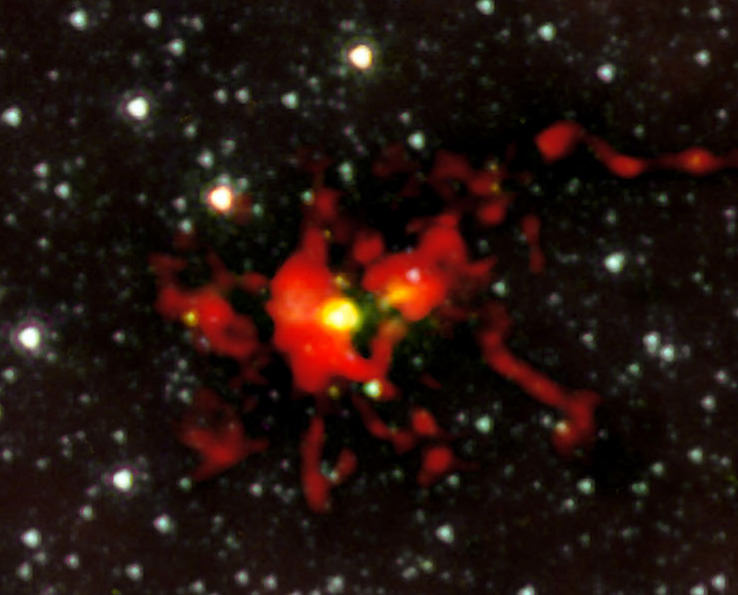

The image above, a combination of data acquired by both Spitzer and ALMA (see below for separate images) shows tendrils of infalling material flowing toward a bright center where the huge protostar is located. These observations show how such massive stars form — through a steady collapse of the entire cloud, rather than through fragmented clustering.

“Even though we already believed that the region was a good candidate for being a massive star-forming cloud, we were not expecting to find such a massive embryonic star at its center,” said Peretto. “This object is expected to form a star that is up to 100 times more massive than the Sun. Only about one in ten thousand of all the stars in the Milky Way reach that kind of mass!”

(Although, with at least 200 billion stars in the galaxy, that means there are still 20 million such giants roaming around out there!)

Read more on the ESO news release here.

Image credits: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/NASA/JPL-Caltech/GLIMPSE