Astronomers think about half of the stars in our Milky Way galaxy are, unlike our Sun, part of a binary system where two stars orbit each other. However, they’ve also thought there was a limit on how close the two stars could be without merging into one single, bigger star. But now a team of astronomers have discovered four pairs of stars in very tight orbits that were thought to be impossibly close. These newly discovered pairs orbit each other in less than 4 hours.

Over the last three decades, observations have shown a large population of stellar binaries, and none of them had an orbital period shorter than 5 hours. Most likely, the stars in these systems were formed close together and have been in orbit around each other from birth onwards.

A team of astronomers using the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT) in Hawaii made the first investigation of red dwarf binary systems. Red dwarfs can be up to ten times smaller and a thousand times less luminous than the Sun. Although they form the most common type of star in the Milky Way, red dwarfs do not show up in normal surveys because of their dimness in visible light.

But astronomers using UKIRT have been monitoring the brightness of hundreds of thousands of stars, including thousands of red dwarfs, in near-infrared light, using its state-of-the-art Wide-Field Camera (WFC).

“To our complete surprise, we found several red dwarf binaries with orbital periods significantly shorter than the 5 hour cut-off found for Sun-like stars, something previously thought to be impossible,” said Bas Nefs from Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, lead author of the paper which was published in journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. “It means that we have to rethink how these close-in binaries form and evolve.”

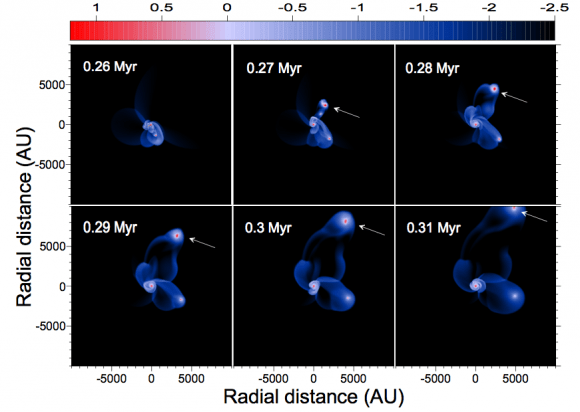

Since stars shrink in size early in their lifetime, the fact that these very tight binaries exist means that their orbits must also have shrunk as well since their birth, otherwise the stars would have been in contact early on and have merged. However, it is not at all clear how these orbits could have shrunk by so much.

One possible scenario is that cool stars in binary systems are much more active and violent than previously thought.

The astronomers said it is possible that the magnetic field lines radiating out from the cool star companions get twisted and deformed as they spiral in towards each other, generating the extra activity through stellar wind, explosive flaring and star spots. Powerful magnetic activity could apply the brakes to these spinning stars, slowing them down so that they move closer together.

“The active nature of these stars and their apparently powerful magnetic fields has profound implications for the environments around red dwarfs throughout our Galaxy, ” said team member said David Pinfield from the University of Hertfordshire.

UKIRT has a 3.8 meter diameter mirror, and is the second largest dedicated infrared telescope in the world. It sits at an altitude of 4,200 m on the top of the volcano Mauna Kea on the island of Hawaii.

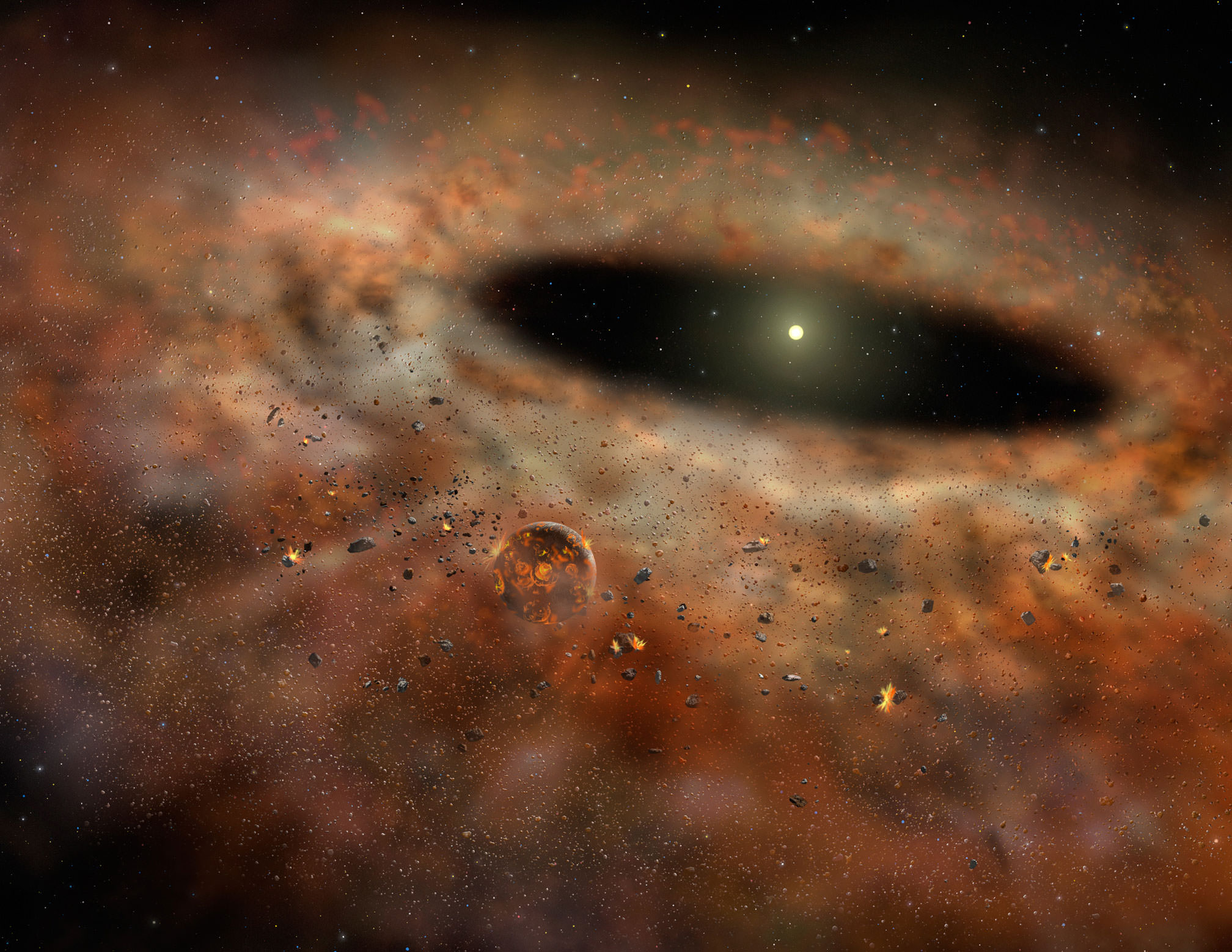

Lead image caption: This artist’s impression shows the tightest of the new record breaking binary systems. Two active M4 type red dwarfs orbit each other every 2.5 hours, as they continue to spiral inwards. Eventually they will coalesce into a single star. Credit: J. Pinfield.