Three more potentially Earthlike worlds have been discovered in our galactic backyard, announced online today by the European Southern Observatory. Researchers using the 60-cm TRAPPIST telescope at ESO’s La Silla observatory in Chile have identified three Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting a star just 40 light-years away.

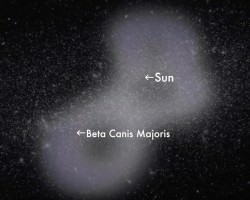

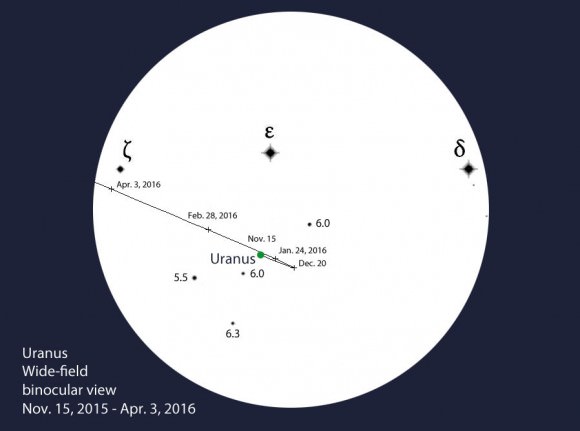

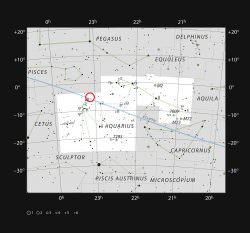

The star, originally classified as 2MASS J23062928-0502285 but now known more conveniently as TRAPPIST-1, is a dim “ultracool” red dwarf star only .05% as bright as our Sun . Located in the constellation Aquarius, it’s now the 37th-farthest star known to host orbiting exoplanets.

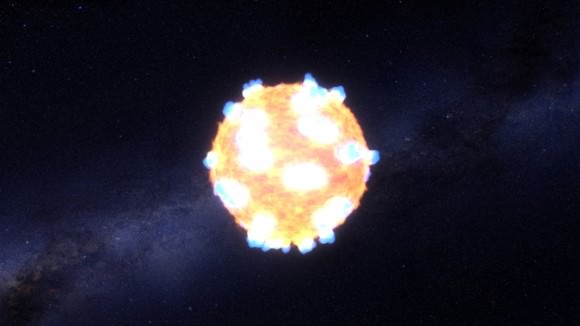

The exoplanets were discovered via the transit method (TRAPPIST stands for Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope) through which the light from a star is observed to dim slightly by planets passing in front of it from our point of view. This is the same method that NASA’s Kepler spacecraft has used to find over 1,000 confirmed exoplanets.

As an ultracool dwarf TRAPPIST-1 is a very small and dim and isn’t easily visible from Earth, but it’s its very dimness that has allowed its planets to be discovered with existing technology. Their subtle silhouettes may have been lost in the glare of larger, brighter stars.

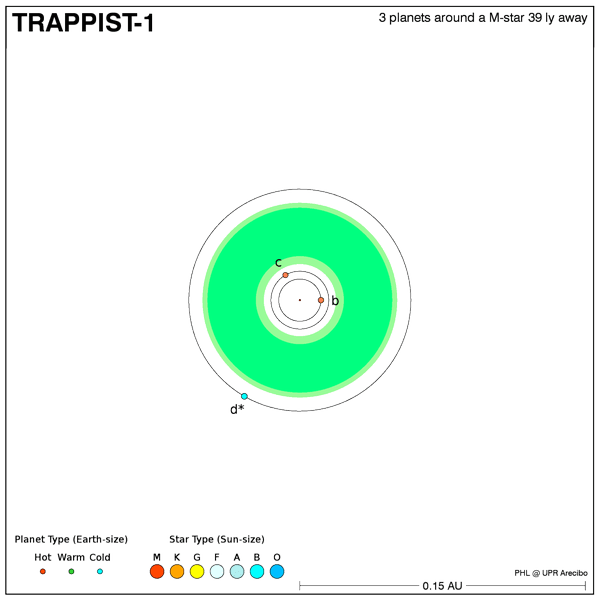

Follow-up measurements of the three exoplanets indicated that they are all approximately Earth-sized and have temperatures ranging from Earthlike to Venuslike (which is, admittedly, a fairly large range.) They orbit their host star very closely with periods measured in Earth days, not years.

“With such short orbital periods, the planets are between 20 and 100 times closer to their star than the Earth to the Sun,” said Michael Gillon, lead author of the research paper. “The structure of this planetary system is much more similar in scale to the system of Jupiter’s moons than to that of the Solar System.”

Although these three new exoplanets are Earth-sized they do not yet classify as “potentially habitable,” at least by the standards of the Planetary Habitability Laboratory (PHL) operated by the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. The planets fall outside PHL’s required habitable zone; two are too close to the host star and one is too far away.

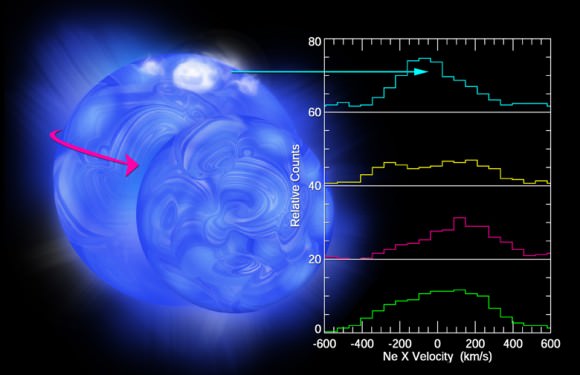

In addition there are certain factors that planets orbiting ultracool dwarfs would have to contend with in order to be friendly to life, not the least of which is the exposure to energetic outbursts from solar flares.

This does not guarantee that the exoplanets are completely uninhabitable, though; it’s entirely possible that there are regions on or within them where life could exist, not unlike Mars or some of the moons in our own Solar System.

The exoplanets are all likely tidally locked in their orbits, so even though the closest two are too hot on their star-facing side and too cold on the other, there may be regions along the east or west terminators that maintain a climate conducive to life.

“Now we have to investigate if they’re habitable,” said co-author Julien de Wit at MIT in Cambridge, Mass. “We will investigate what kind of atmosphere they have, and then will search for biomarkers and signs of life.”

Discovering three planets orbiting such a small yet extremely common type of star hints that there are likely many, many more such worlds in our galaxy and the Universe as a whole.

“So far, the existence of such ‘red worlds’ orbiting ultra-cool dwarf stars was purely theoretical, but now we have not just one lonely planet around such a faint red star but a complete system of three planets,” said study co-author Emmanuel Jehin.

The team’s research was presented in a paper entitled “Temperate Earth-sized planets transiting a nearby ultracool dwarf star” and will be published in Nature.

________________

Note: the original version of this article described 2MASS J23062928-0502285 (TRAPPIST-1) as a brown dwarf based on its classification on the Simbad archive. But at M8V it is “definitely a star,” according to co-author Julien de Wit in an email, although at the very low end of the red dwarf line. Corrections have been made above.