This is a classic trick question. Ask a friend, “what is the closest star?” and then watch as they try to recall some nearby stars. Sirius maybe? Alpha something or other? Betelgeuse?

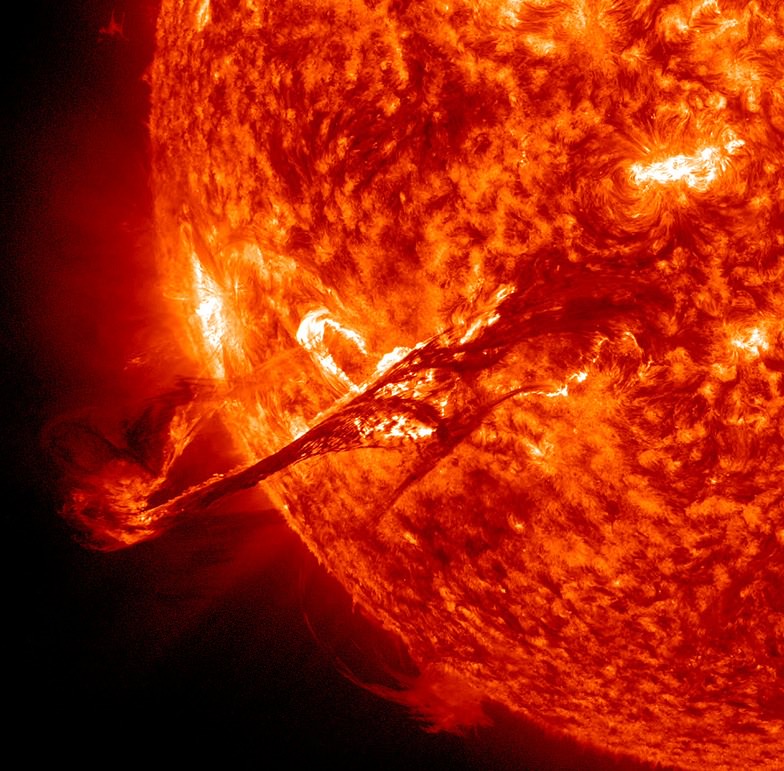

The answer, obviously, is the Sun; that massive ball of plasma located a mere 150 million km from Earth.

Let’s be more precise; what’s the closest star to the Sun?

Closest Star

You might have heard that it’s Alpha Centauri, the third brightest star in the sky, just 4.37 light-years from Earth.

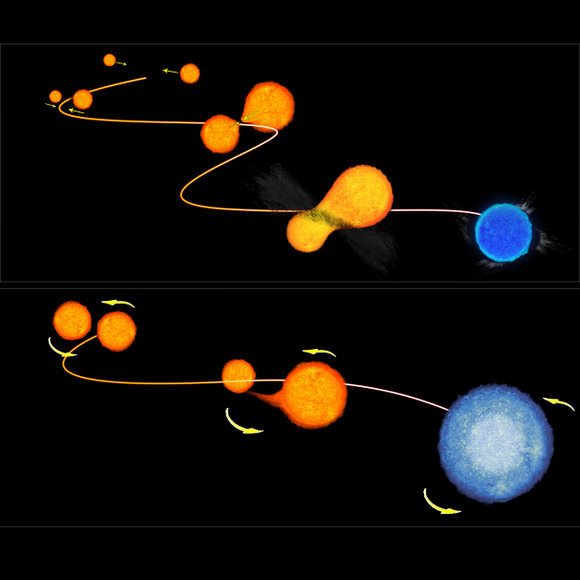

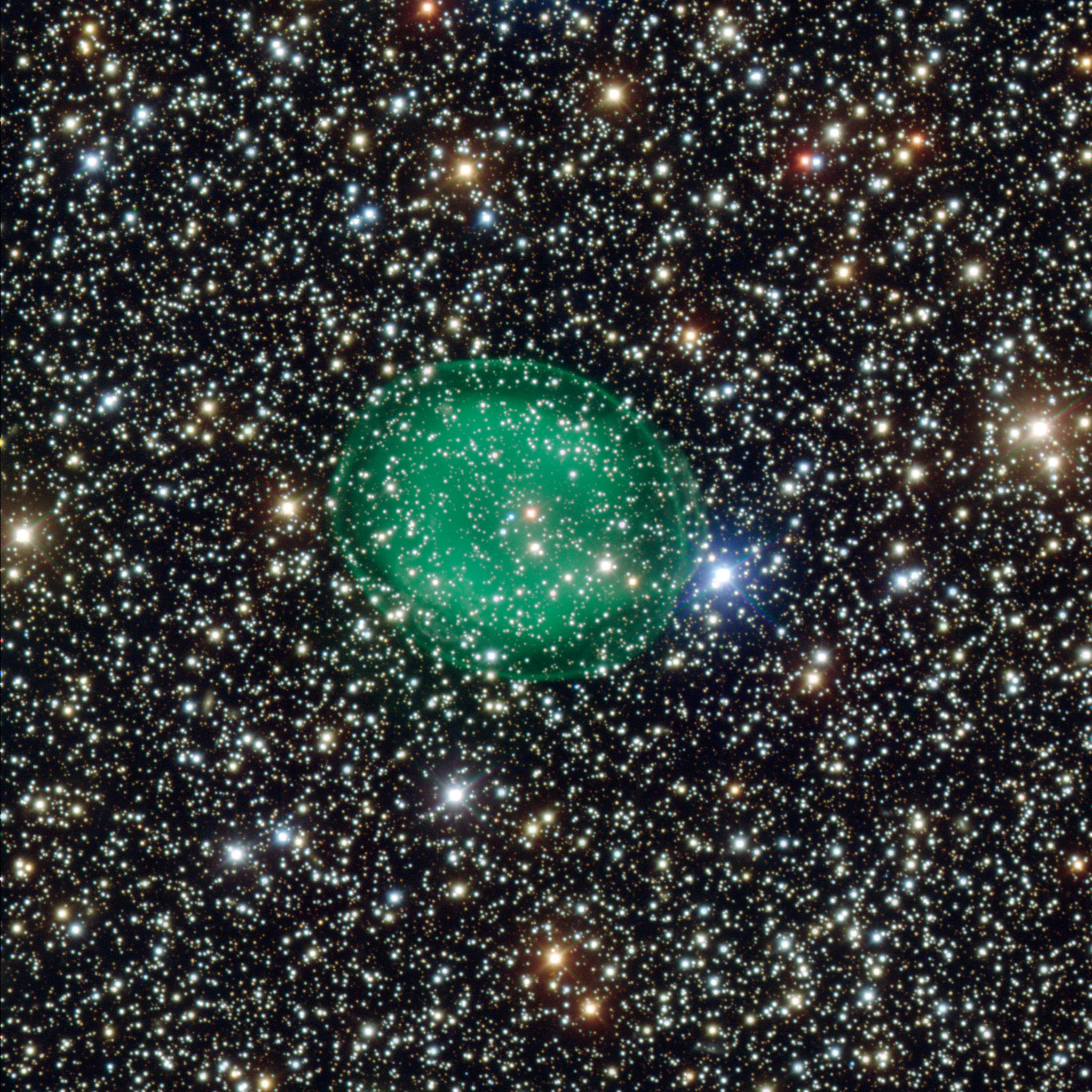

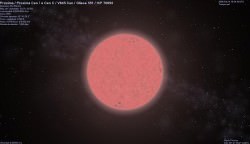

But Alpha Centauri isn’t one star, it’s a system of three stars. First, there’s a binary pair, orbiting a common center of gravity every 80 years. Alpha Centauri A is just a little more massive and brighter than the Sun, and Alpha Centauri B is slightly less massive than the Sun. Then there’s a third member of this system, the faint red dwarf star, Proxima Centauri.

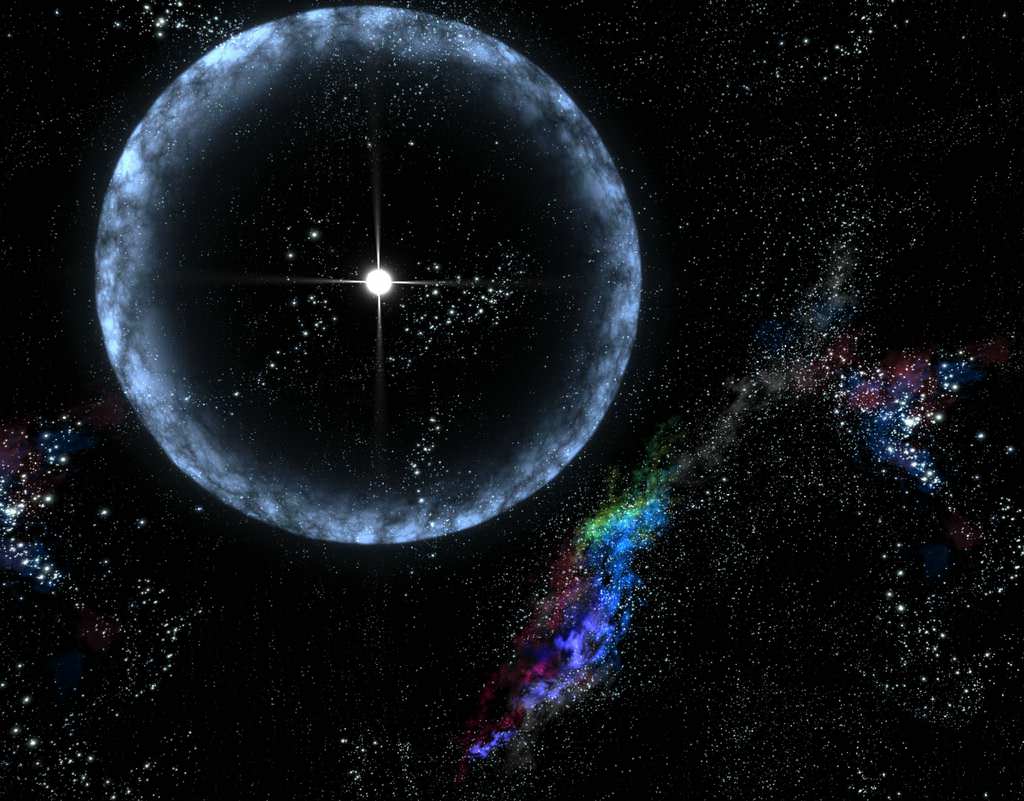

It’s the closest star to our Sun, located just a short 4.24 light-years away.

Alpha Centauri is located in the Centaurus constellation, which is only visible in the Southern Hemisphere. Unfortunately, even if you can see the system, you can’t see Proxima Centauri. It’s so dim, you need a need a reasonably powerful telescope to resolve it.

Let’s get sense of scale for just how far away Proxima Centauri really is. Think about the distance from the Earth to Pluto. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft travels at nearly 60,000 km/h, the fastest a spacecraft has ever traveled in the Solar System. It will have taken more than nine years to make this journey when it arrives in 2015. Travelling at this speed, to get to Proxima Centauri, it would take New Horizons 78,000 years.

Proxima Centauri has been the nearest star for about 32,000 years, and it will hold this record for another 33,000 years. It will make its closest approach to the Sun in about 26,700 years, getting to within 3.11 light-years of Earth. After 33,000 years from now, the nearest star will be Ross 248.

What About the Northern Hemisphere?

The closest star that you can see with the naked eye in the Northern Hemisphere is Sirius, the Dog Star. Sirius, has twice the mass and is almost twice the size of the Sun, and it’s the brightest star in the sky. Located 8.6 light-years away in the constellation Canis Major – it’s very familiar as the bright star chasing Orion across the night sky in Winter.

How do Astronomers Measure the Distance to Stars?

They use a technique called parallax. Do a little experiment here. Hold one of your arms out at length and put your thumb up so that it’s beside some distant reference object. Now take turns opening and closing each eye. Notice how your thumb seems to jump back and forth as you switch eyes? That’s the parallax method.

To measure the distance to stars, you measure the angle to a star when the Earth is one side of its orbit; say in the summer. Then you wait 6 month, until the Earth has moved to the opposite side of its orbit, and then measure the angle to the star compared to some distant reference object. If the star is close, the angle will be measurable, and the distance can be calculated.

You can only really measure the distance to the nearest stars this way, since it only works to about 100 light-years.

The 20 Closest Stars

Here is a list of the 20 closest star systems and their distance in light-years. Some of these have multiple stars, but they’re part of the same system.

- Alpha Centauri – 4.2

- Barnard’s Star – 5.9

- Wolf 359 – 7.8

- Lalande 21185 – 8.3

- Sirius – 8.6

- Luyten 726-8 – 8.7

- Ross 154 – 9.7

- Ross 248 – 10.3

- Epsilon Eridani – 10.5

- Lacaille 9352 – 10.7

- Ross 128 – 10.9

- EZ Aquarii – 11.3

- Procyon – 11.4

- 61 Cygni – 11.4

- Struve 2398 – 11.5

- Groombridge 34 – 11.6

- Epison Indi – 11.8

- Dx Carncri – 11.8

- Tau Ceti – 11.9

- GJ 106 – 11.9

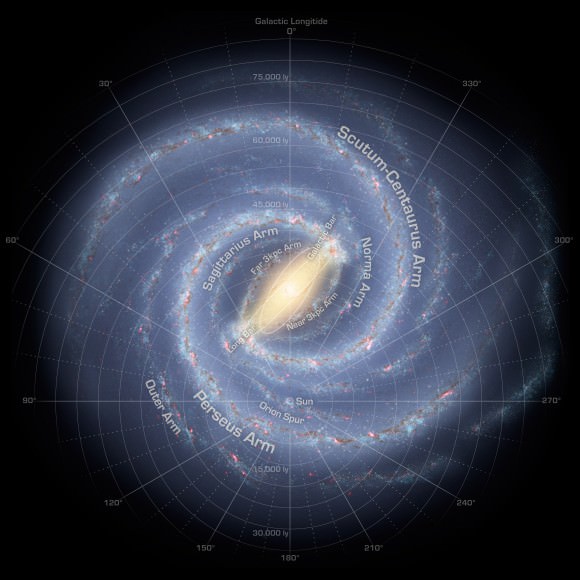

According to NASA data, there are 45 stars within 17 light years of the Sun. There are thought to be as many as 200 billion stars in our galaxy. Some are so faint that they are nearly impossible to detect. Maybe, with technological improvements, scientists will find even closer stars.