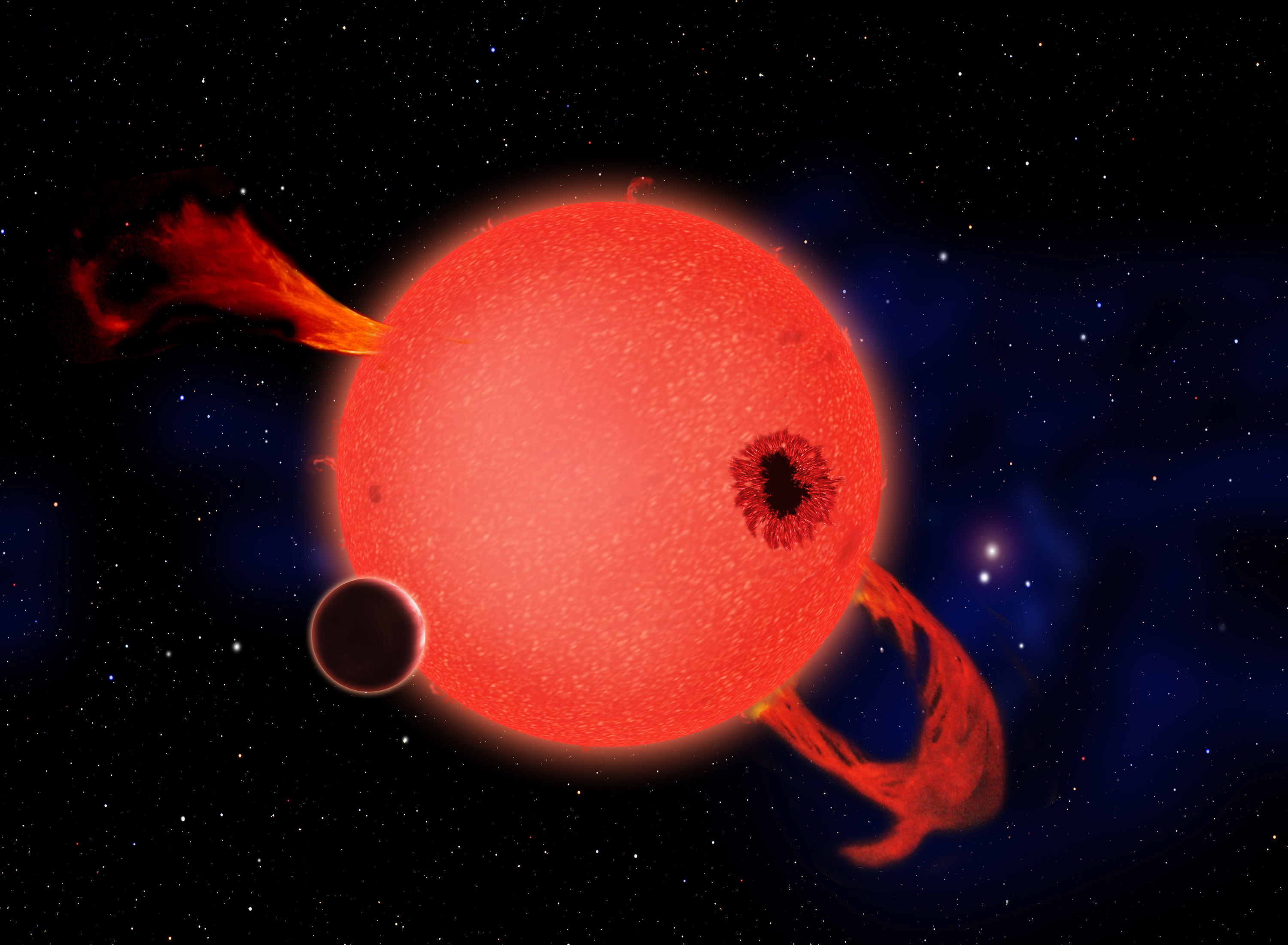

Artist’s concept of brown dwarf 2MASSJ22282889-431026 (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The complex weather patterns within the atmosphere of a rapidly-rotating brown dwarf have been mapped in the highest detail ever by researchers using the infrared abilities of NASA’s Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes… talk about solar wind!

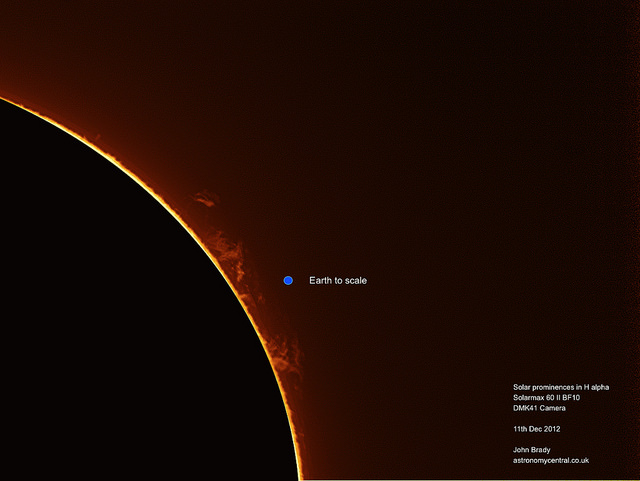

Sometimes referred to as failed stars, brown dwarfs form from condensing gas and dust like regular stars but never manage to gather enough mass to ignite full-on hydrogen fusion in their cores. As a result they more resemble enormous Jupiter-like planets, radiating low levels of heat while possessing bands of wind-driven eddies in their upper atmospheric layers.

Although brown dwarfs are by their nature very dim, and thus difficult to observe in visible wavelengths of light, their heat can be detected by Hubble and the Spitzer Space Telescope — both of which can “see” just fine in near- and far-infrared, respectively.

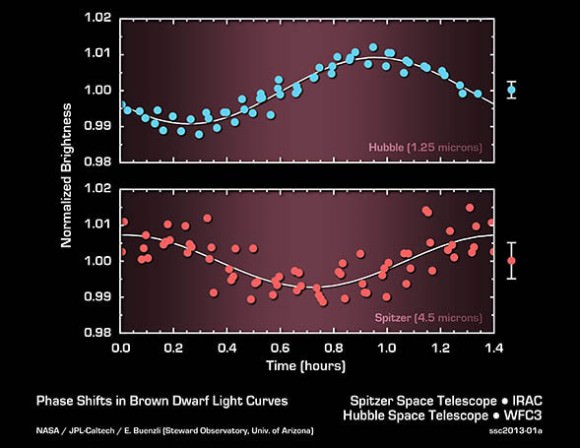

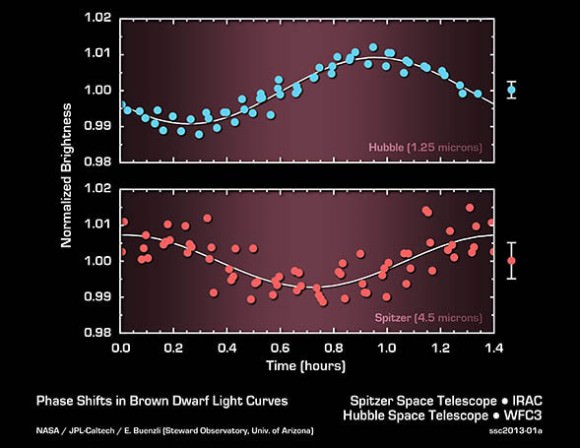

Led by researchers from the University of Arizona, a team of astronomers used these orbiting observatories on July 7, 2011 to measure the light curves from a brown dwarf named 2MASSJ22282889-431026 (2M2228 for short.) What they found was that while 2M2228 exhibited periodic brightening in both near- and far-infrared over the course of its speedy 1.43-hour rotation, the amount and rate of brightening varied between the different wavelengths detected by the two telescopes.

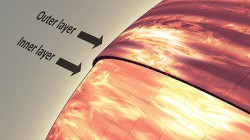

“With Hubble and Spitzer, we were able to look at different atmospheric layers of a brown dwarf, similar to the way doctors use medical imaging techniques to study the different tissues in your body.”

– Daniel Apai, principal investigator, University of Arizona

This unexpected variance — or phase shift — most likely indicates different layers of cloud material and wind velocities surrounding 2M2228, swirling around the dwarf star in very much the same way as the stormy cloud bands seen on Jupiter or Saturn.

But while the clouds on Jupiter are made of gases like ammonia and methane, the clouds of 2M2228 are made of much more unusual stuff.

“Unlike the water clouds of Earth or the ammonia clouds of Jupiter, clouds on brown dwarfs are composed of hot grains of sand, liquid drops of iron, and other exotic compounds,” said Mark Marley, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and co-author of the paper. “So this large atmospheric disturbance found by Spitzer and Hubble gives a new meaning to the concept of extreme weather.”

“Unlike the water clouds of Earth or the ammonia clouds of Jupiter, clouds on brown dwarfs are composed of hot grains of sand, liquid drops of iron, and other exotic compounds,” said Mark Marley, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and co-author of the paper. “So this large atmospheric disturbance found by Spitzer and Hubble gives a new meaning to the concept of extreme weather.”

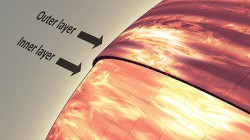

While it might seem strange to think about weather on a star, remember that brown dwarfs are much more gas planet-like than “real” stars. Although the temperatures of 1,100–1,600 ºF (600–700 ºC) found on 2M2228 might sound searingly hot, it’s downright chilly compared to even regular stars like our Sun, which has an average temperature of nearly 10,000 ºF (5,600 ºC). Different materials gather at varying layers of its atmosphere, depending on temperature and pressure, and can be penetrated by different wavelengths of infrared light — just like gas giant planets.

“What we see here is evidence for massive, organized cloud systems, perhaps akin to giant versions of the Great Red Spot on Jupiter,” said Adam Showman, a theorist at the University of Arizona involved in the research. “These out-of-sync light variations provide a fingerprint of how the brown dwarf’s weather systems stack up vertically. The data suggest regions on the brown dwarf where the weather is cloudy and rich in silicate vapor deep in the atmosphere coincide with balmier, drier conditions at higher altitudes — and vice versa.”

The team’s results were presented today, January 8, during the 221st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Long Beach, CA.

Read more on the Spitzer site, and find the team’s paper in PDF form here.

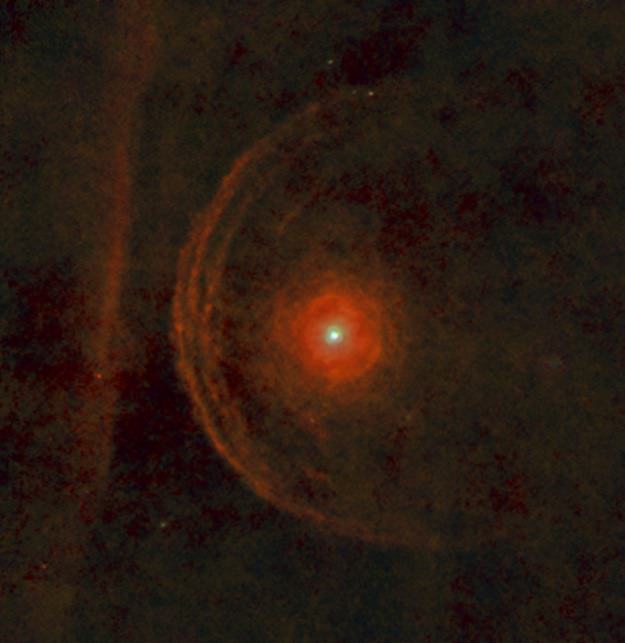

Inset image: the anatomy of a brown dwarf’s atmosphere (NASA/JPL).

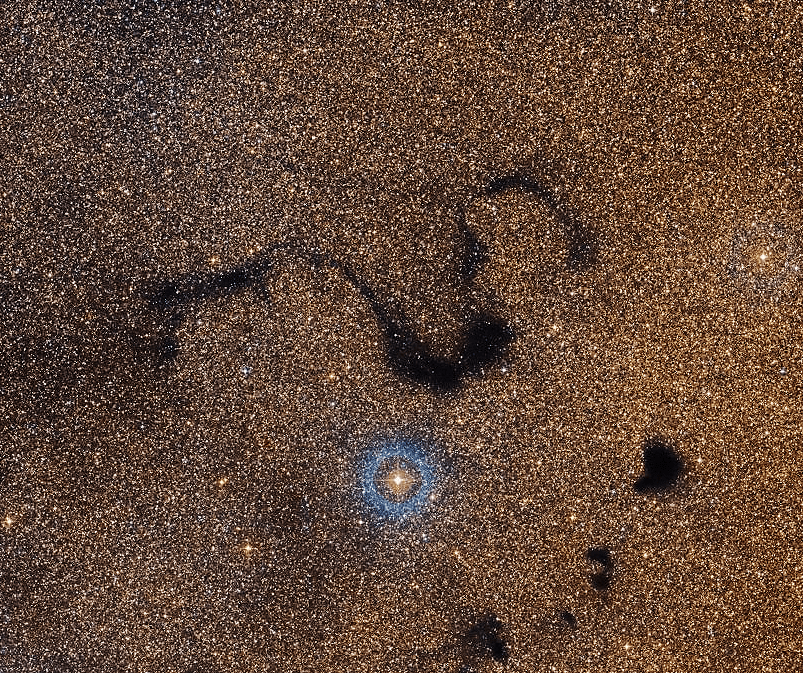

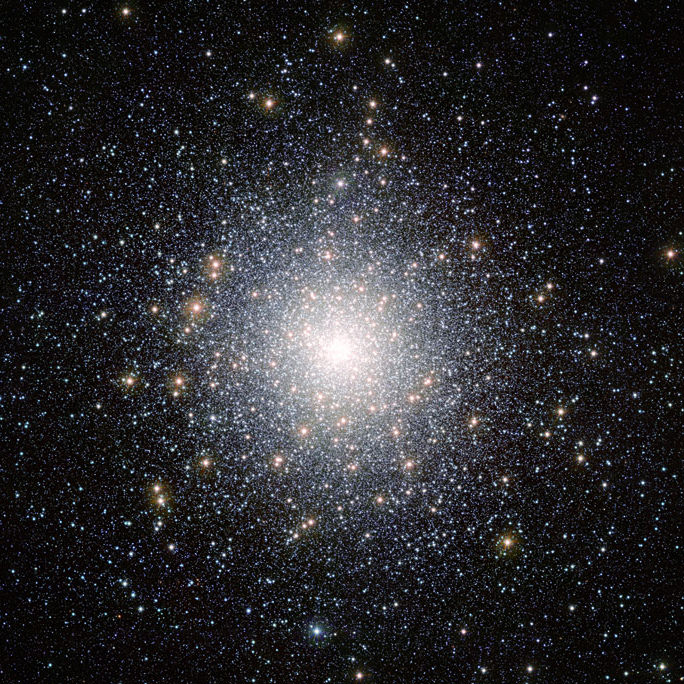

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.

The background stars in the image are part of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which was in the distance behind 47 Tucanae when this image was taken.