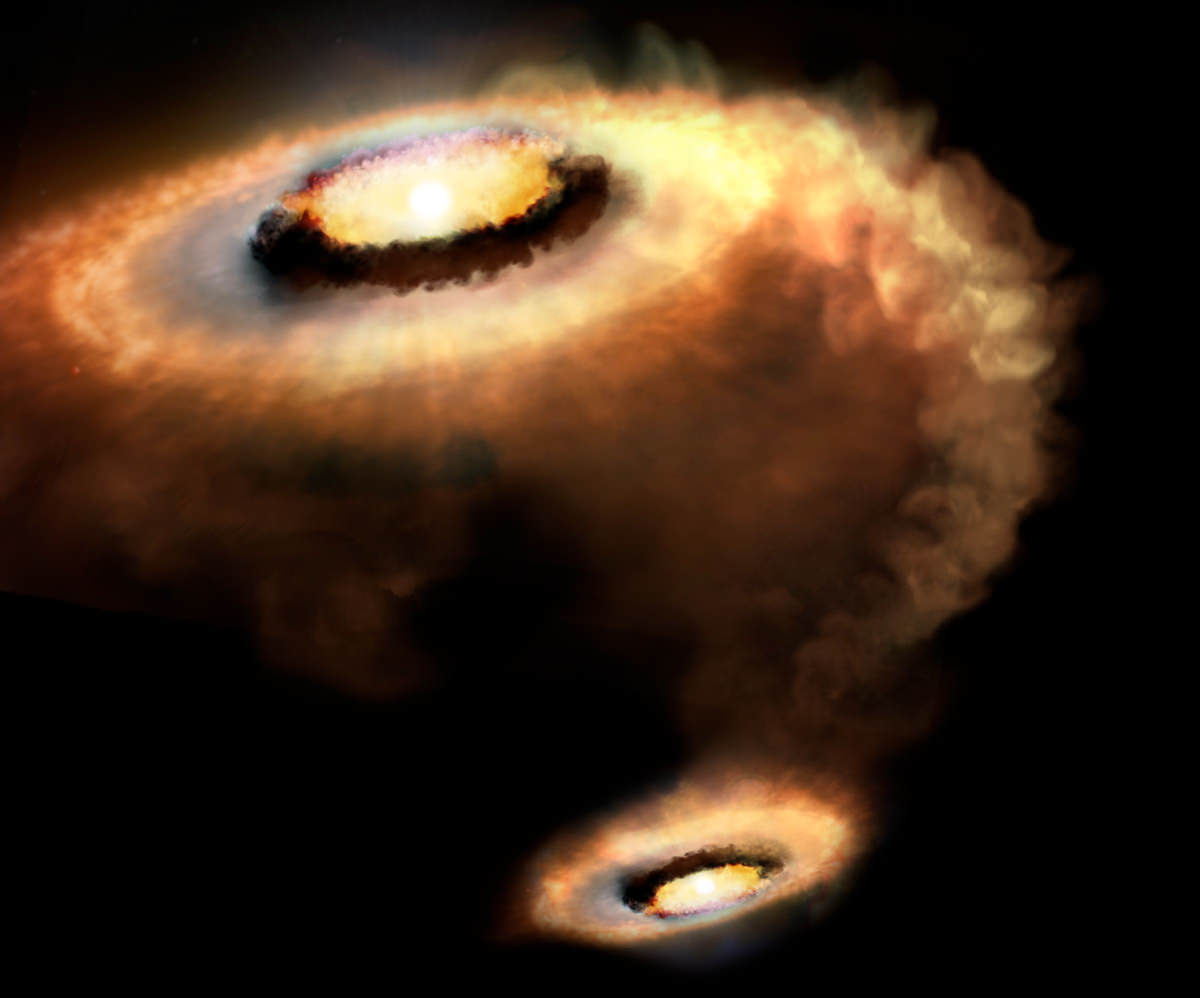

There’s nothing more out of this world than quasi-stellar objects or more simply – quasars. These are the most powerful and among the most distant objects in the Universe. At their center is a black hole with the mass of a million or more Suns. And these powerhouses are fairly compact – about the size of our Solar System. Understanding how they came to be and how — or if — they evolve into the galaxies that surround us today are some of the big questions driving astronomers.

Now, a new paper by Yue Shen and Luis C. Ho – “The diversity of quasars unified by accretion and orientation” in the journal Nature confirms the importance of a mathematical derivation by the famous astrophysicist Sir Arthur Eddington during the first half of the 20th Century, in understanding not just stars but the properties of quasars, too. Ironically, Eddington did not believe black holes existed, but now his derivation, the Eddington Luminosity, can be used more reliably to determine important properties of quasars across vast stretches of space and time.

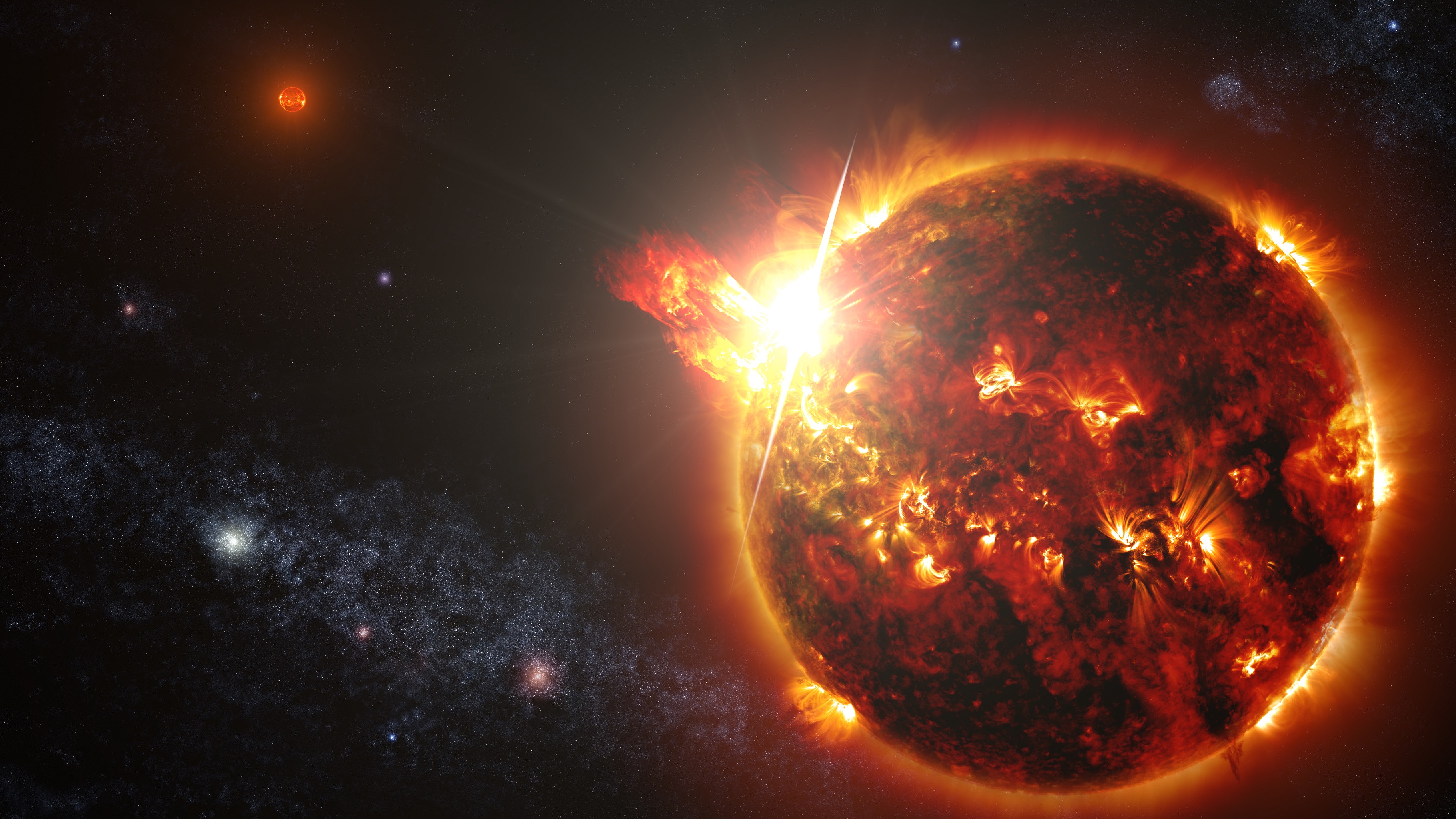

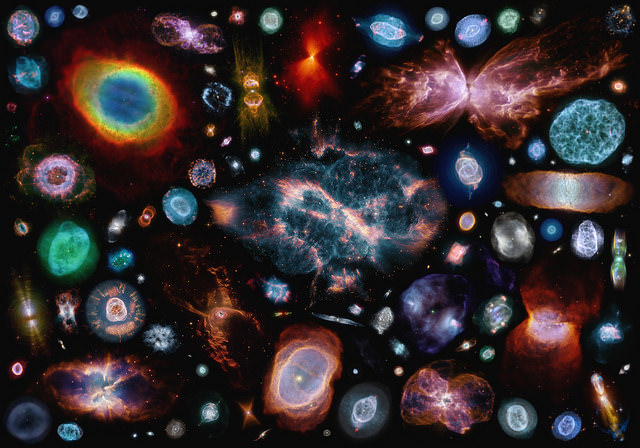

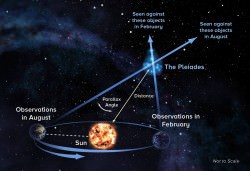

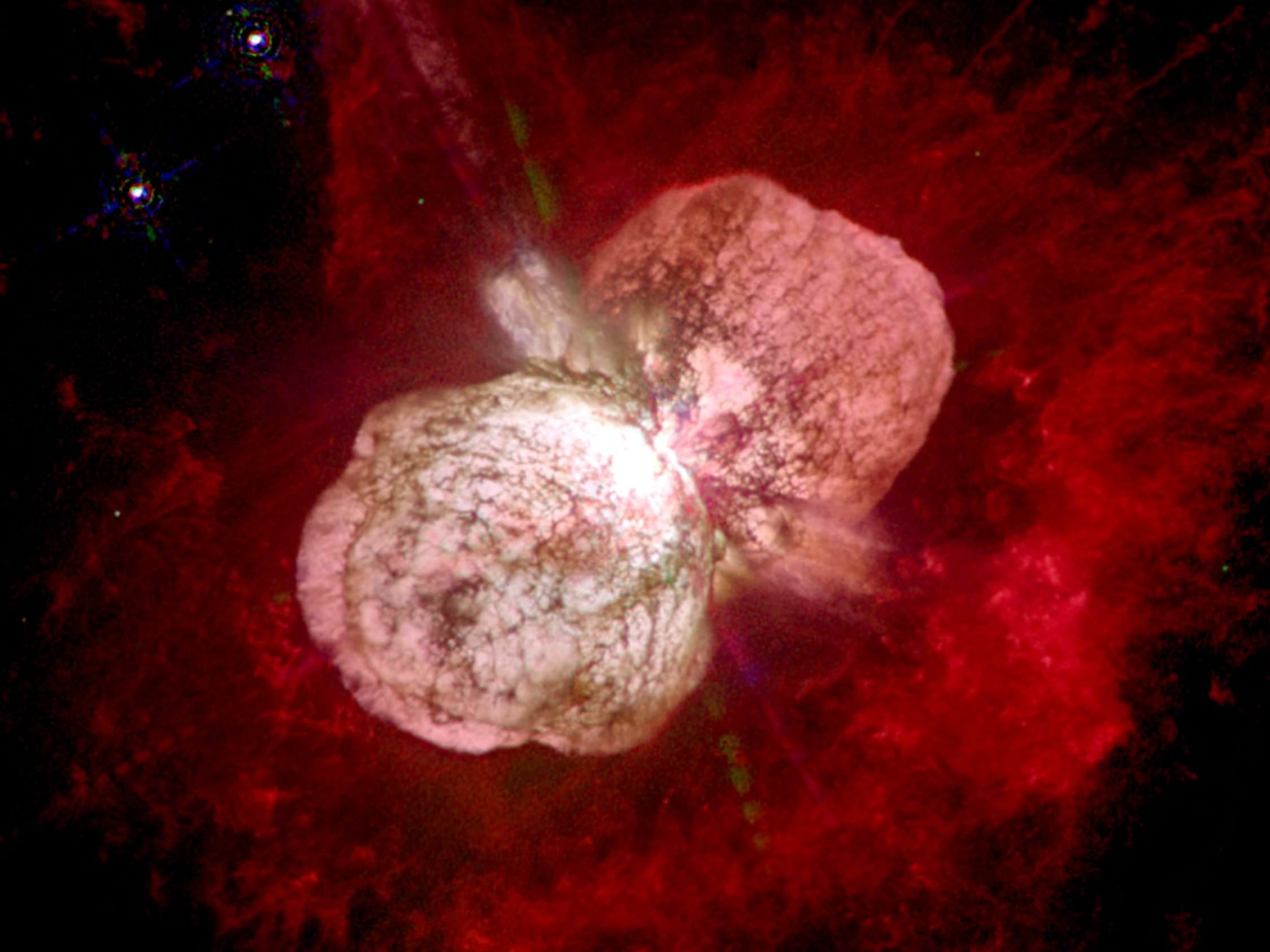

A quasar is recognized as an accreting (meaning- matter falling upon) super massive black hole at the center of an “active galaxy”. Most known quasars exist at distances that place them very early in the Universe; the most distant is at 13.9 billion light years, a mere 770 million years after the Big Bang. Somehow, quasars and the nascent galaxies surrounding them evolved into the galaxies present in the Universe today. At their extreme distances, they are point-like, indistinguishable from a star except that the spectra of their light differ greatly from a star’s. Some would be as bright as our Sun if they were placed 33 light years away meaning that they are over a trillion times more luminous than our star.

The Eddington luminosity defines the maximum luminosity that a star can exhibit that is in equilibrium; specifically, hydrostatic equilibrium. Extremely massive stars and black holes can exceed this limit but stars, to remain stable for long periods, are in hydrostatic equilibrium between their inward forces – gravity – and the outward electromagnetic forces. Such is the case of our star, the Sun, otherwise it would collapse or expand which in either case, would not have provided the stable source of light that has nourished life on Earth for billions of years.

Generally, scientific models often start simple, such as Bohr’s model of the hydrogen atom, and later observations can reveal intricacies that require more complex theory to explain, such as Quantum Mechanics for the atom. The Eddington luminosity and ratio could be compared to knowing the thermal efficiency and compression ratio of an internal combustion engine; by knowing such values, other properties follow.

Several other factors regarding the Eddington Luminosity are now known which are necessary to define the “modified Eddington luminosity” used today.

The new paper in Nature shows how the Eddington Luminosity helps understand the driving force behind the main sequence of quasars, and Shen and Ho call their work the missing definitive proof that quantifies the correlation of a quasar properties to a quasar’s Eddington ratio.

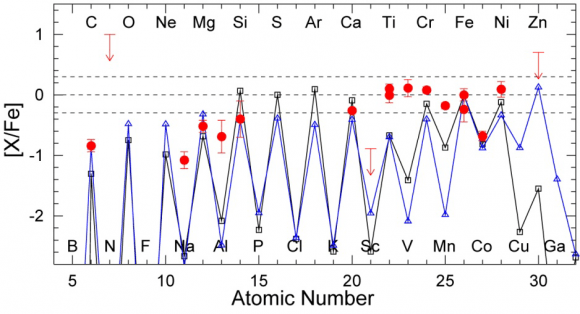

They used archival observational data to uncover the relationship between the strength of the optical Iron [Fe] and Oxygen[O III] emissions – strongly tied to the physical properties of the quasar’s central engine – a super-massive black hole, and the Eddington ratio. Their work provides the confidence and the correlations needed to move forward in our understanding of quasars and their relationship to the evolution of galaxies in the early Universe and up to our present epoch.

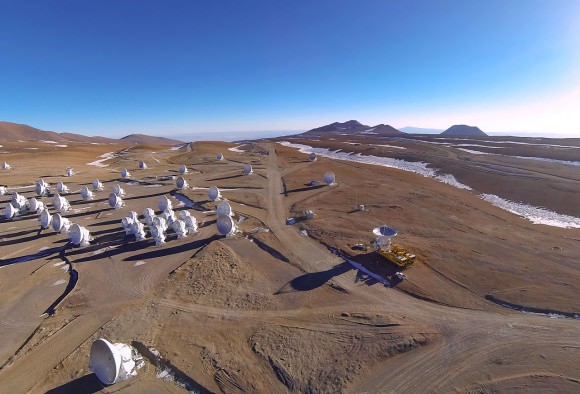

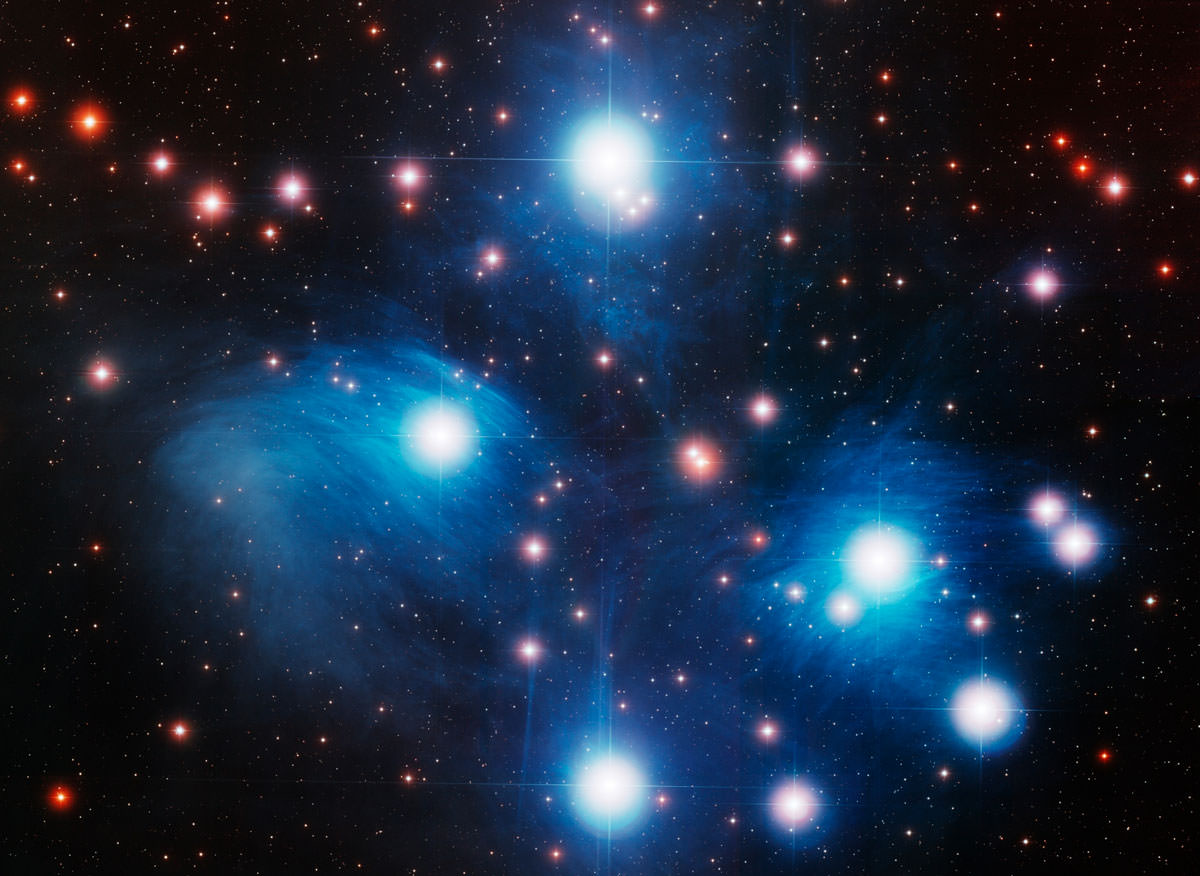

Astronomers have been studying quasars for a little over 50 years. Beginning in 1960, quasar discoveries began to accumulate but only through radio telescope observations. Then, a very accurate radio telescope measurement of Quasar 3C 273 was completed using a Lunar occultation. With this in hand, Dr. Maarten Schmidt of California Institute of Technology was able to identify the object in visible light using the 200 inch Palomar Telescope. Reviewing the strange spectral lines in its light, Schmidt reached the right conclusion that quasar spectra exhibit an extreme redshift and it was due to cosmological effects. The cosmological redshift of quasars meant that they are at a great distance from us in space and time. It also spelled the demise of the Steady-State theory of the Universe and gave further support to an expanding Universe that emanated from a singularity – the Big Bang.

The researchers, Yue Shen and Luis C. Ho are from the Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at Peking University working with the Carnegie Observatories, Pasadena, California.

References and further reading:

“The diversity of quasars unified by accretion and orientation”, Yue Shen, Luis C. Ho, Sept 11, 2014, Nature

“What is a Quasar?”, Universe Today, Fraser Cain, August 12, 2013

“Interview with Maarten Schmidt”, Caltech Oral Histories, 1999

“Fifty Years of Quasars, a Symposium in honor of Maarten Schmidt”, Caltech, Sept 9, 2013