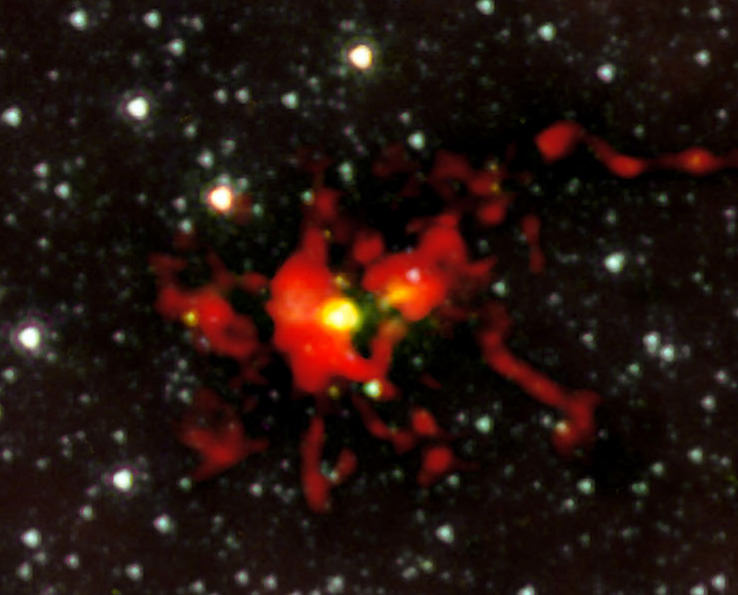

The incredible visual appearance of planetary nebulae are some of the most studied and observed of deep space objects. However, these enigmatic clouds of gas have defied explanation as to their shapes and astronomers are seeking answers. Thanks to a new discovery made by an international team of scientists from Sweden, Germany and Austria, we have now observed a jet of high-energy particles in the process of being ejected from an expiring star.

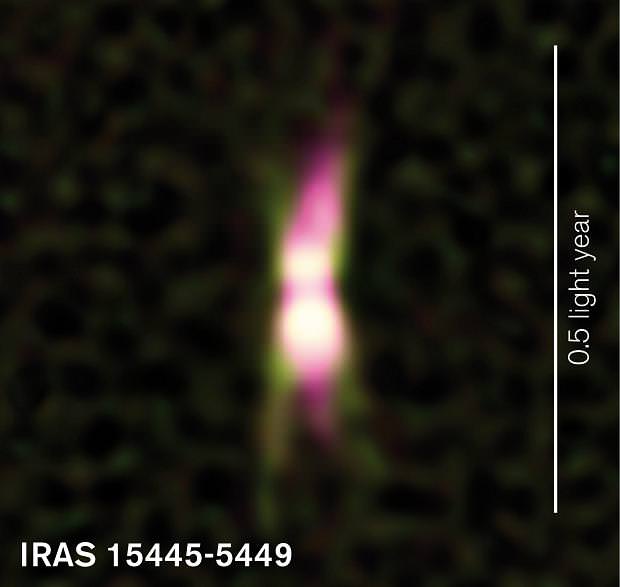

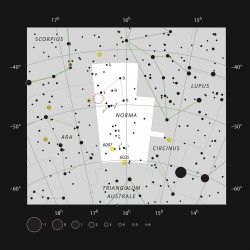

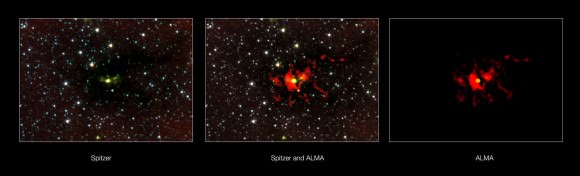

When a sun-like star reaches the end of its life, it begins to shed itself of its outer layers. These layers blossom into space at speeds of a few kilometers per second, forming a variety of shapes and sizes – yet we know little about what causes their ultimate appearance. Now astronomers are taking a close look at a rather normal star that has reached the end of its life and is beginning to form a planetary nebula. Cataloged as IRAS 15445-5449, this stellar study resides 230,000 light years away in the constellation of Triangulum Australe (the Southern Triangle). Through the use of the CSIRO Australia Telescope Compact Array, a compliment of six 22-meter radio telescopes in New South Wales, Australia, researchers have found what may be the answer to this mystery… high-speed magnetic jets.

“In our data we found the clear signature of a narrow and extremely energetic jet of a type which has never been seen before in an old, Sun-like star,” says Andrés Pérez Sánchez, graduate student in astronomy at Bonn University, who led the study.

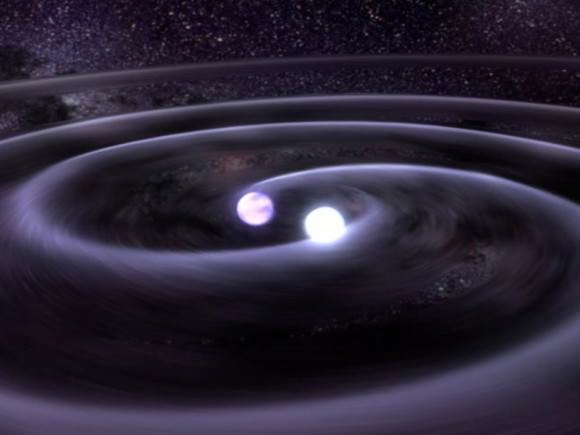

How does a radio telescope aid researchers in an optical study? In this case the radio waves emitted by the dying star are compatible with the trademark high-energy particles they are expected to produce. These “spouts” of particles travel at nearly the speed of light and coincident jets are also known to emanate from other astronomical objects that range from newborn stars to supermassive black holes.

“What we’re seeing is a powerful jet of particles spiraling through a strong magnetic field,” says Wouter Vlemmings, astronomer at Onsala Space Observatory, Chalmers. “Its brightness indicates that it’s in the process of creating a symmetric nebula around the star.”

Will these high-energy particles contained within the jet eventually craft the planetary nebula into an ethereal beauty? According to the astronomers, the current state of IRAS 15445-5449 is probably a short-lived phenomenon and nothing more than an intense and dramatic phase in its life… One we’re lucky to have observed.

“The radio signal from the jet varies in a way that means that it may only last a few decades. Over the course of just a few hundred years the jet can determine how the nebula will look when it finally gets lit up by the star,” says team member Jessica Chapman, astronomer at CSIRO in Sydney, Australia.

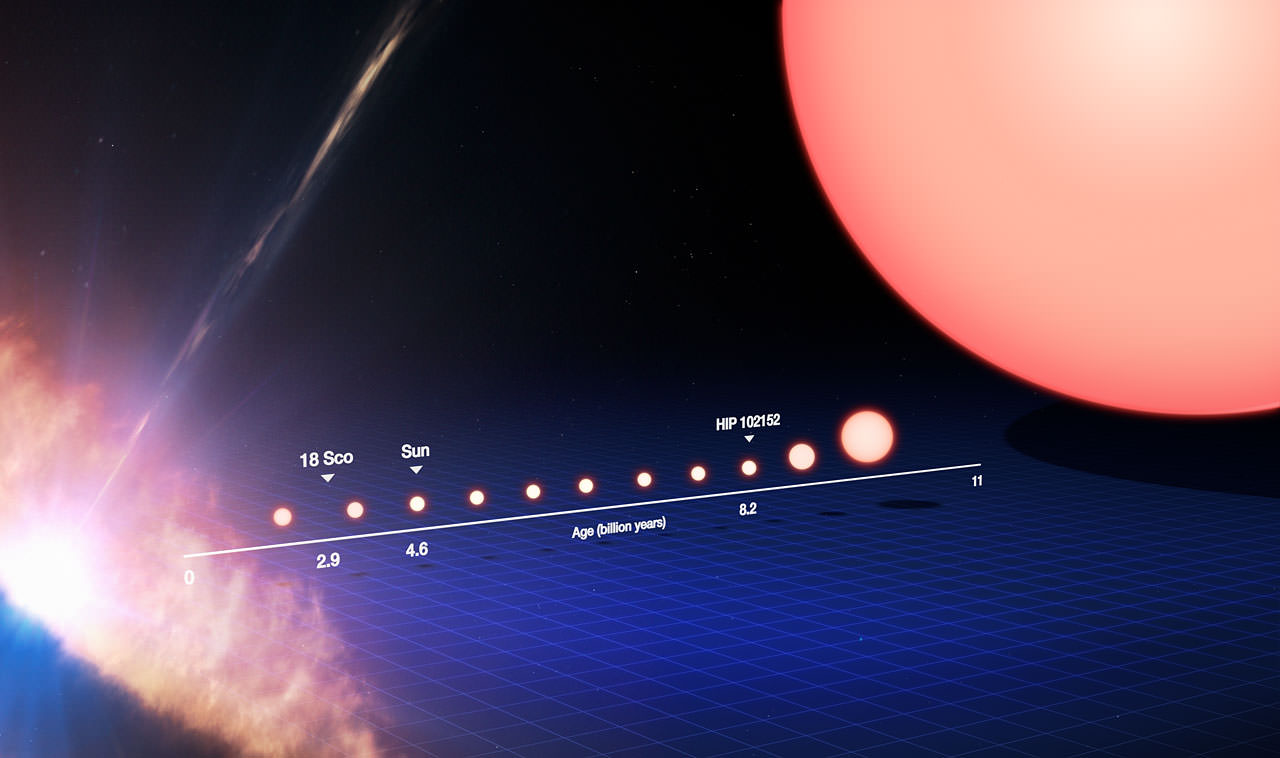

Will our Sun also follow suit? Right now the answer is unclear. There may be more to this radio picture than meets the ear. However, rest assured that this new information is being heard and might well become the target of additional radio studies. Considering the life of a planetary nebula is generally expected to last few tens of thousands of years, this is a unique opportunity for astronomers to observe what might be a transient occurrence.

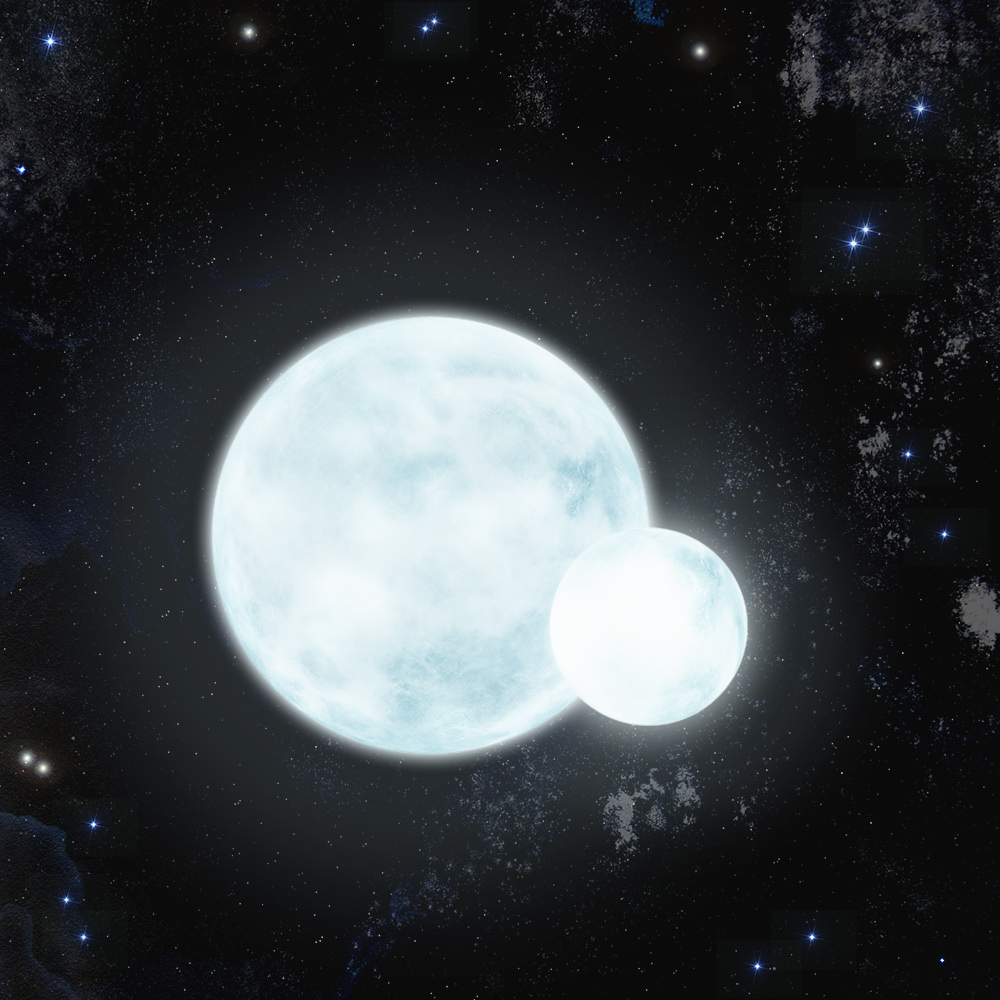

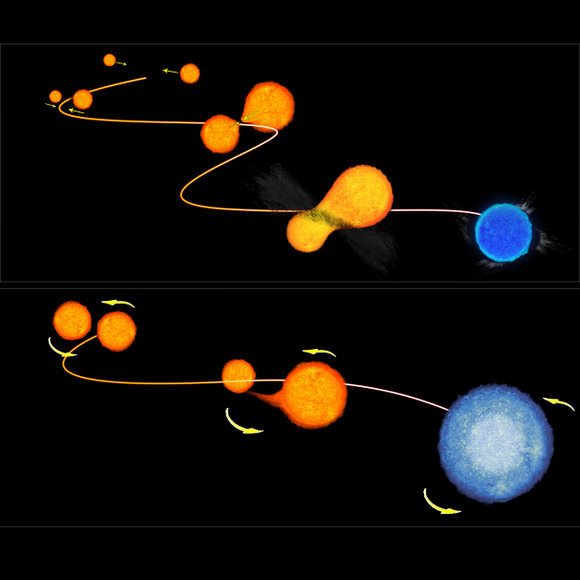

“The star may have an unseen companion – another star or large planet — that helps create the jet. With the help of other front-line radio telescopes, like ALMA, and future facilities like the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), we’ll be able to find out just which stars create jets like this one, and how they do it,” says Andrés Pérez Sánchez.

Original Story Source: Royal Astronomical Society News Release.