[/caption]

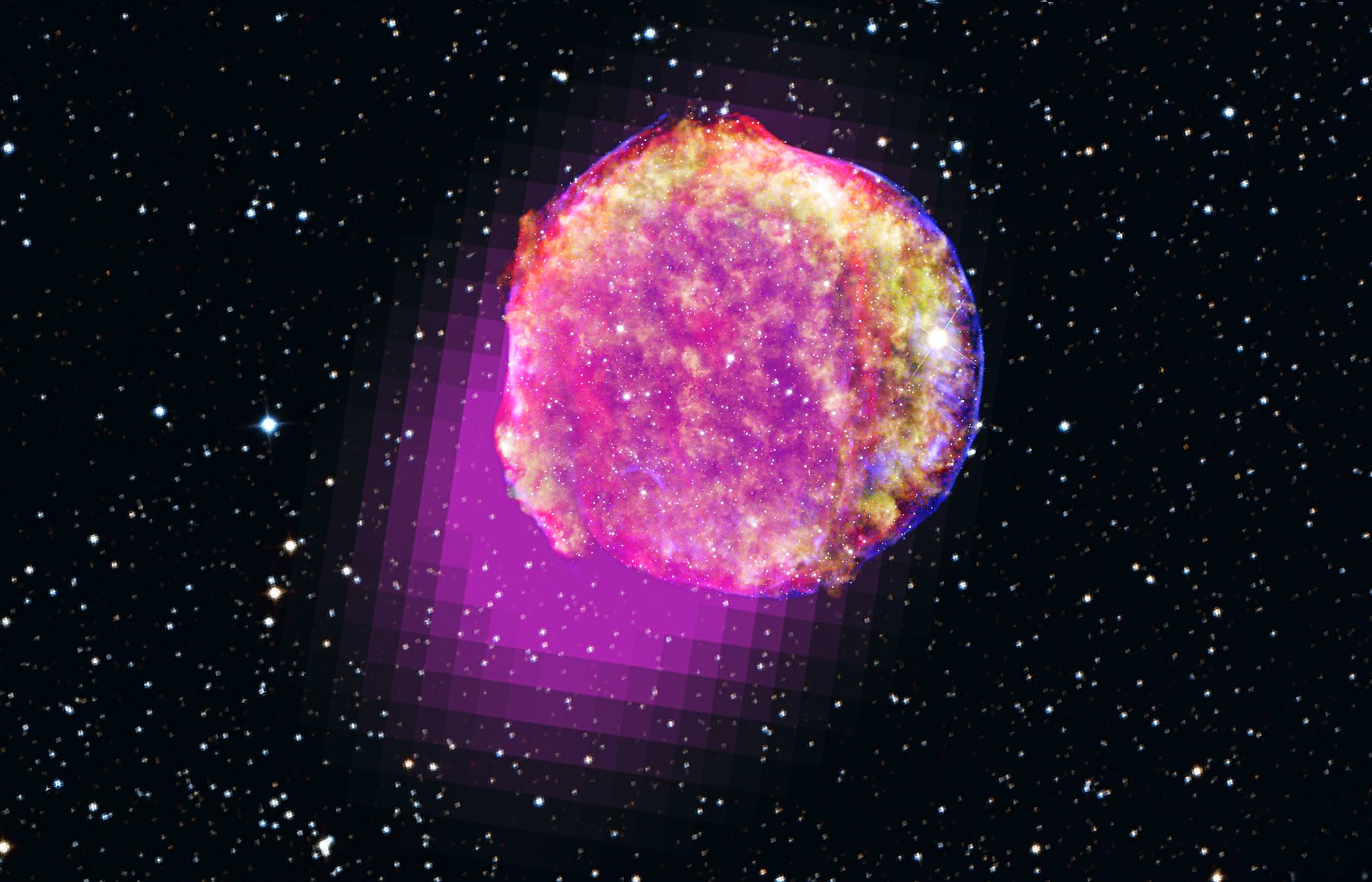

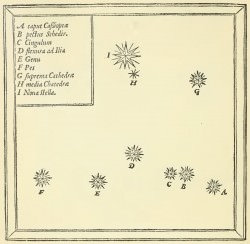

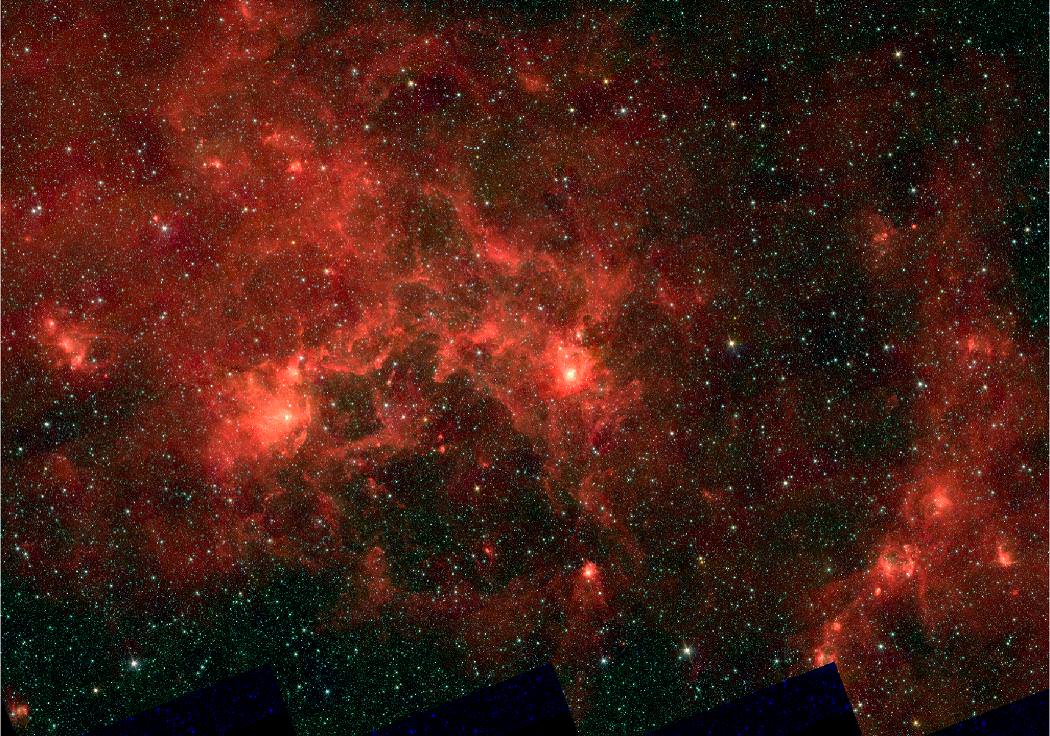

The sprawling northern constellation of Draco is home to a monumental galactic merger which left a singular spectacle – NGC 5907. Surrounded by an ethereal garment of wispy star trails and currents of stellar material, this spiral galaxy is the survivor of a “clash of the dragons” which may have occurred some 8 to 9 billion years ago. Recent theory suggests galaxies of this type may be the product of a larger galaxy encountering a smaller satellite – but this might not be the case. Not only is NGC 5907 a bit different in some respects, it’s a lot different in others… and peculiar motion is just the beginning.

“If the disc of many spirals is indeed rebuilt after a major merger, it is expected that tidal tails can be a fossil record and that there should be many loops and streams in their halos. Recently Martínez-Delgado et al. (2010) have conducted a pilot survey of isolated spiral galaxies in the Local Volume up to a low surface brightness sensitivity of ~28.5 mag/arcsec2 in V band. They find that many of these galaxies have loops or streams of various shapes and interpret these structures as evidence of minor merger or satellite infall.” says J. Wang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “However, if these loops are caused by minor mergers, the residual of the satellite core should be detected according to numerical simulations. Why is it hardly ever detected?”

The “why” is indeed the reason NGC 5907 is being intensively studied by a team of six scientists of the Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, Chinese Academy of Sciences, National Astronomical Observatories of China NAOC and Marseille Observatory. Even though NGC 5907 is a member of a galactic group, there are no galaxies near enough to it to be causing an interaction which could account for its streamers of stars. It is truly a warped galaxy with gaseous and stellar disks which extend beyond the nominal cut-off radius. But that’s not all… It also has a peculiar halo which includes a significant fraction of metal enriched stars. NGC 5907 just doesn’t fit the patterns.

“For some of our models, we assume a star formation history with a varying global efficiency in transforming gas to stars, in order to preserve enough gas from being consumed before fusion.” explains the research team. “Although this fine-tuned star formation history may have some physical motivations, its main role is also to ensure the formation of stars after the emergence of the gaseous disc just after fusion.”

Now enter the 32- and 196-core computers at the Paris Observatory center and the 680-core Graphic Processor Unit supercomputer of Beijing NAOC with the capability to run 50000 billion operations per second. By employing several state of the art, hydrodynamical, and numerical simulations with particle numbers ranging from 200 000 to 6 millions, the team’s goal was to show the structure of NGC 5907 may have been the result of the clash of two dragon-sized galaxies… or was it?

“The exceptional features of NGC 5907 can be reproduced, together with the central galaxy properties, especially if we compare the observed loops to the high-order loops expected in a major merger model.” says Wang. “Given the extremely large number of parameters, as well as the very numerous constraints provided by the observations, we cannot claim that we have already identified the exact and unique model of NGC 5907 and its halo properties. We nevertheless succeeded in reproducing the loop geometry, and a disc-dominated, almost bulge-less galaxy.”

In the meantime, major galaxy merger events will continue to be a top priority in formation research. “Future work will include modelling other nearby spiral galaxies with large and faint, extended features in their halos.” concludes the team. “These distant galaxies are likely similar to the progenitors, six billion years ago, of present-day spirals, and linking them together could provide another crucial test for the spiral rebuilding disc scenario.”

And sleeping dragons may one day arise…

Original Story Source: Paris Observatory News. For Further Reading: Loops formed by tidal tails as fossil records of a major merger and Fossils of the Hierarchical Formation of the Nearby Spiral Galaxy NGC 5907.