[/caption]

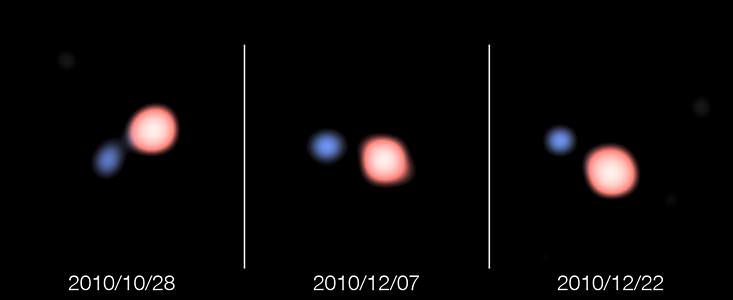

It might be hard to believe, but massive stars are larger in their infant stage than they are when fully formed. Thanks to a team of astronomers at the University of Amsterdam, observations have shown that during the initial stages of creation, super-massive stars are super-sized. This research now confirms the theory that massive stars contract until they reach the age of equilibrium.

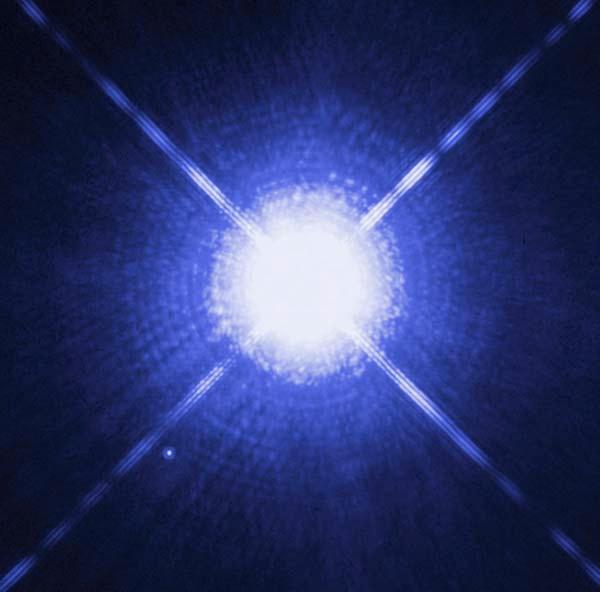

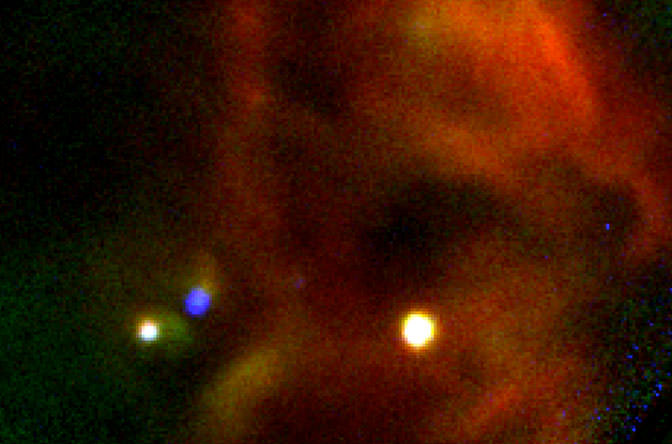

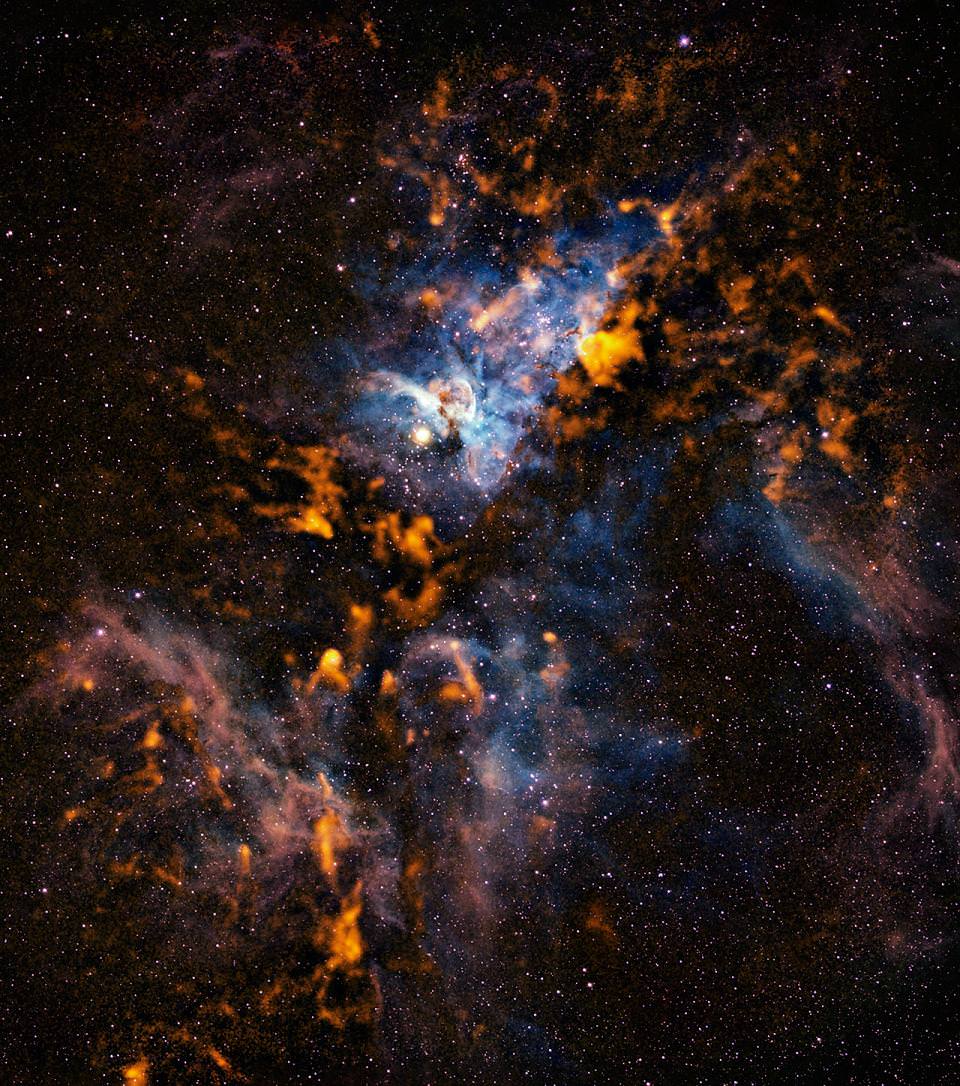

In the past, one of the difficulties in proving this theory has been the near impossibility of getting a clear spectrum of a massive star during formation due to obscuring dust and gases. Now, using the powerful spectrograph X-shooter on ESO’s Very Large Telescope in Chile, researchers have been able to obtain data on a young star cataloged as B275 in the “Omega Nebula” (M17). Built by an international team, the X-shooter has a special wavelength coverage: from 300 nm (UV) to 2500 nm (infrared) and is the most powerful tool of its kind. Its “one shot” image has now provided us with the first solid spectral evidence of a star on its way to main sequence. Seven times more massive than the Sun, B275 has shown itself to be three times the size of a normal main-sequence star. These results help to confirm present modeling.

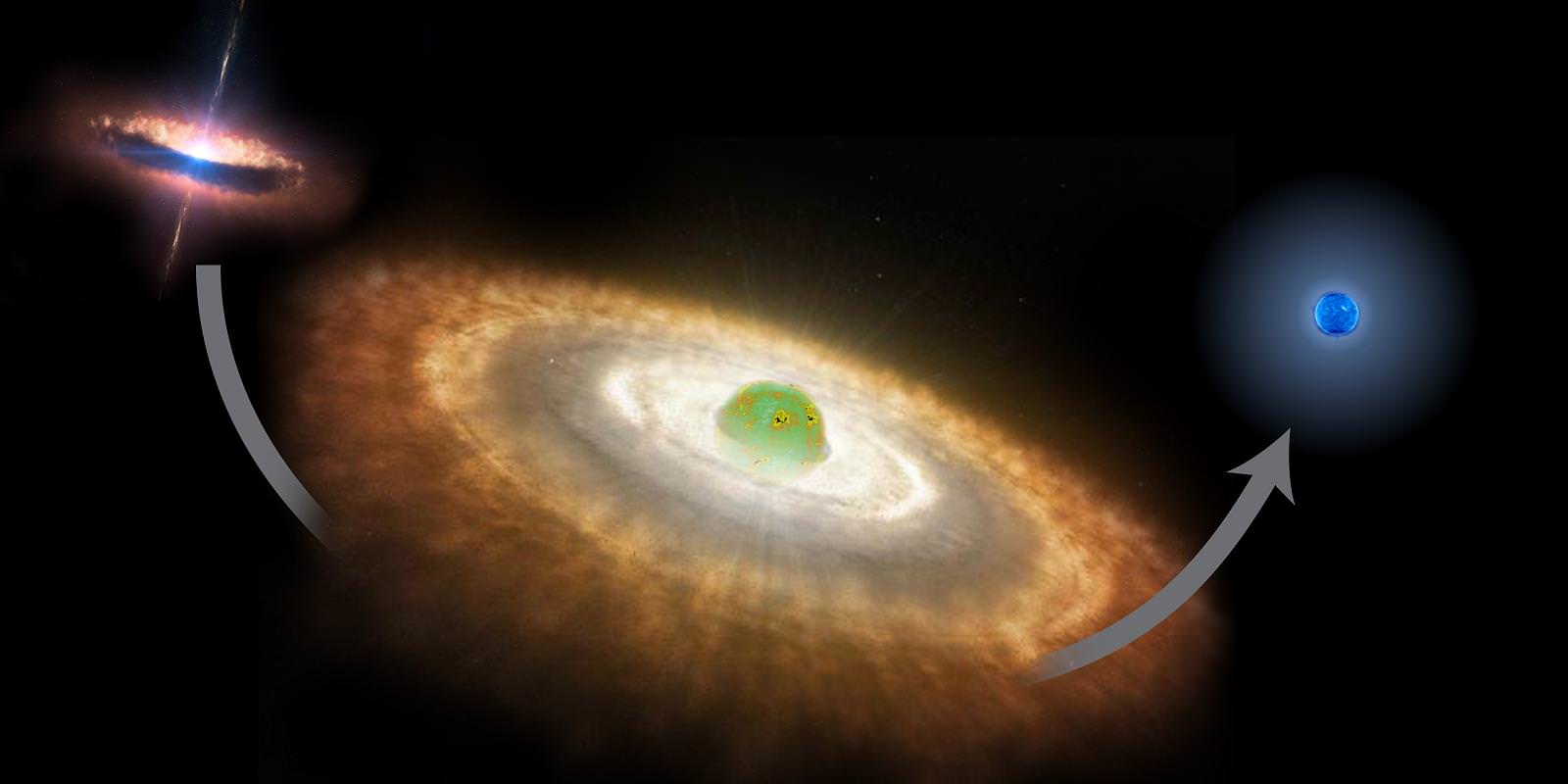

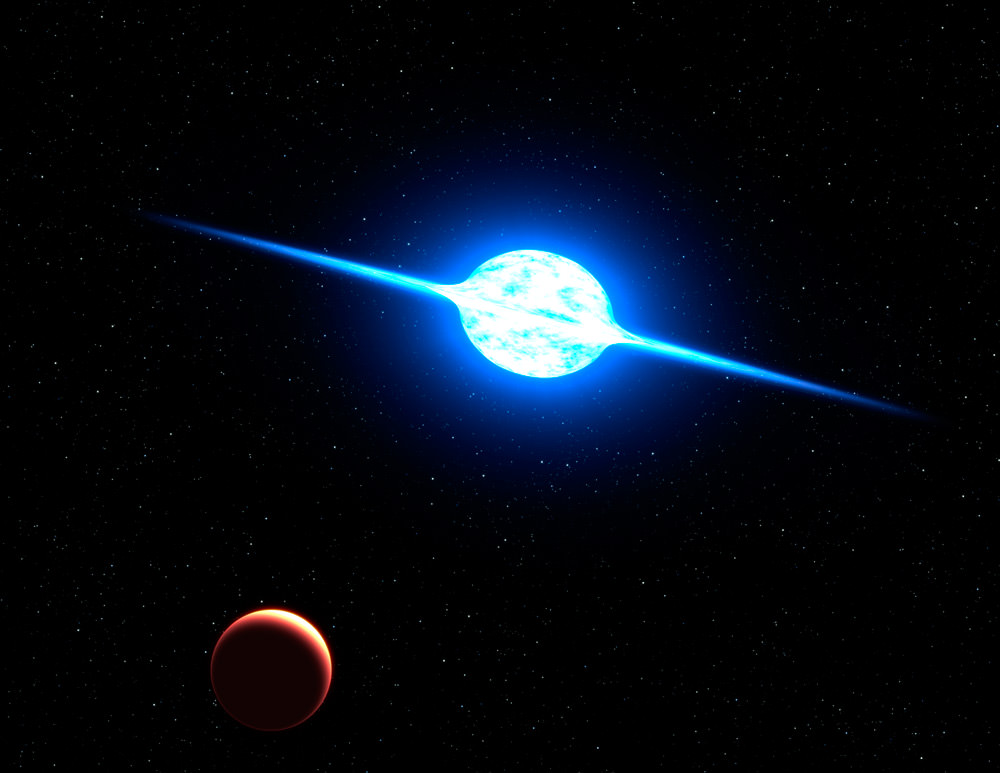

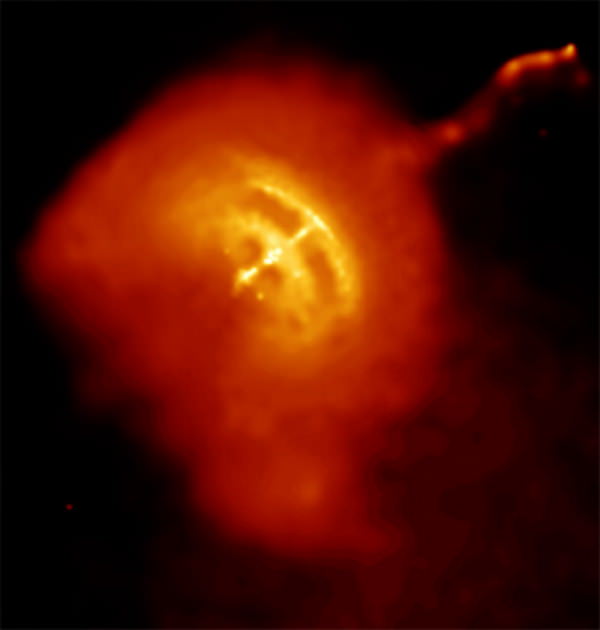

When young, massive stars begin to coalesce, they are shrouded in a rotating gas disk where the mass-accretion process starts. In this state, strong jets are also produced in a very complicated mechanism which isn’t well understood. These actions were reported earlier by the same research group. When accretion is complete, the disk evaporates and the stellar surface then becomes visible. As of now, B275 is displaying these traits and its core temperature has reached the point where hydrogen fusion has commenced. Now the star will continue to contract until the energy production at its center matches the radiation at the surface and equilibrium is achieved. To make the situation even more curious, the X-shooter spectrum has shown B275 to have a measurably lower surface temperature for a star of its type – a very luminous one. This wide margin of difference can be equated to its large radius – and that’s what the results show. The intense spectral lines associated with B275 are consistent with a giant star.

Lead author Bram Ochsendorf, was the man to analyze the spectrum of this curious star as part of his Master’s research program at the University of Amsterdam. He has also began his PhD project in Leiden. Says Ochsendorf, “The large wavelength coverage of X shooter provides the opportunity to determine many stellar properties at once, like the surface temperature, size, and the presence of a disk.”

The spectrum of B275 was obtained during the X-shooter science verification process by co-authors Rolf Chini and Vera Hoffmeister from the Ruhr-Universitaet in Bochum, Germany. “This is a beautiful confirmation of new theoretical models describing the formation process of massive stars, obtained thanks to the extreme sensitivity of X-shooter”, remarks Ochsendorf’s supervisor Prof. Lex Kaper.

Original Story Source: First firm spectral classification of an early-B pre-main-sequence star: B275 in M17.