[/caption]

Star clusters are wonderful test beds for theories of stellar formation and evolution. One of the key roles they play is to help astronomers understand the distribution of stellar masses as stars form (in other words, how many high mass stars versus intermediate and low mass stars), known as the Initial Mass Function (IMF). One of the problems is that this is constantly evolving away from the initial distribution as stars die or are ejected from the cluster. As such, understanding these mechanisms is essential for astronomers looking to backtrack from the current population to the IMF.

To assist in this goal, astronomers led by Vasilii Gvaramadze at the University of Bonn in Germany are engaged in a study to search young clusters for stars in the process of being ejected.

In the first of two studies released by the team so far, they studied the cluster associated with the famous Eagle Nebula. This nebula is well known due to the famous “Pillars of Creation” image taken by the aging Hubble Space Telescope which shows towers of dense gas currently undergoing star formation.

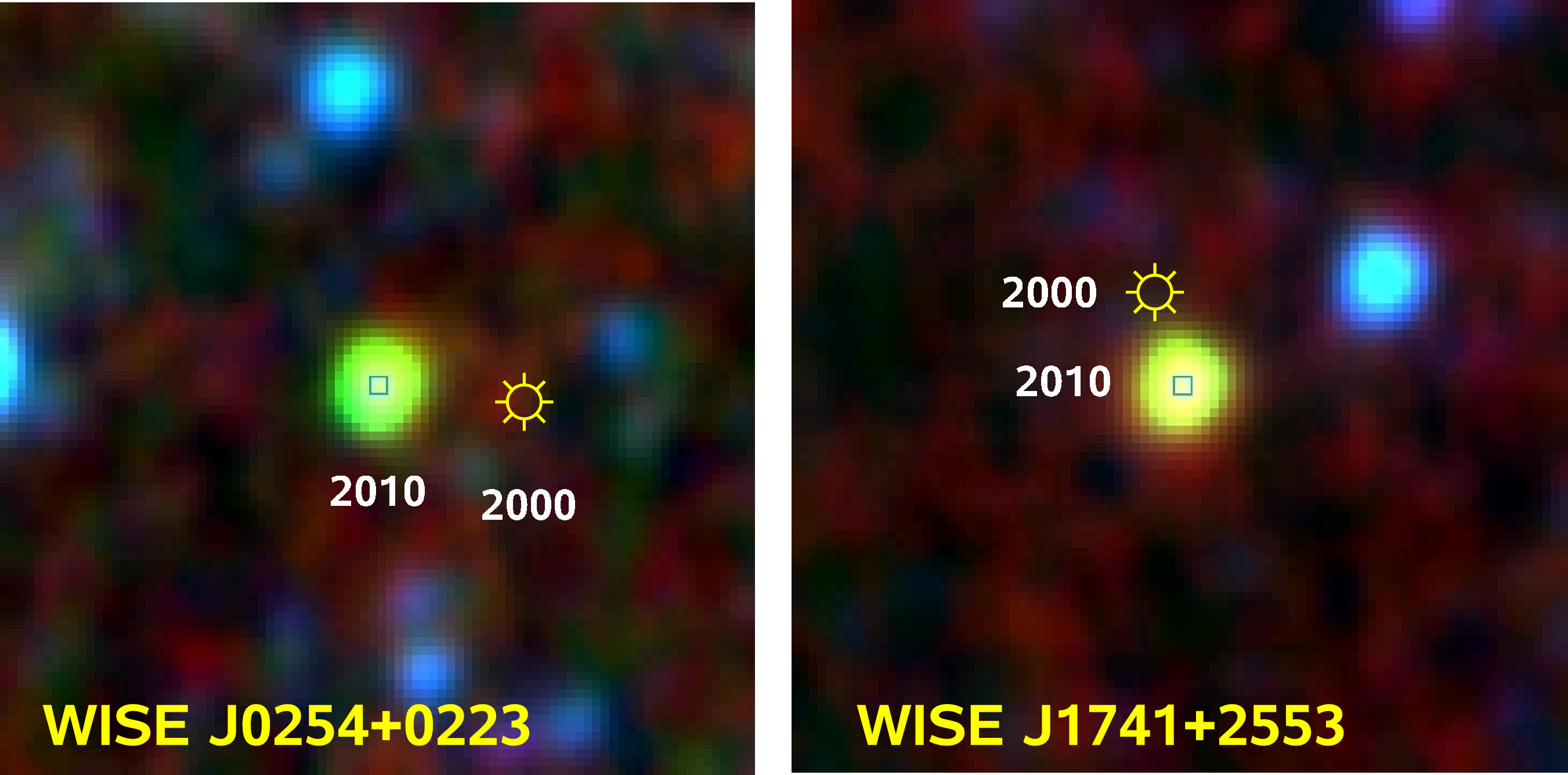

Two main methods exist for discovering stars on the lam from their birthplace. The first is to examine stars individually and analyze their motion in the plane of the sky (proper motion) along with their motion towards or away from us (radial velocity) to determine if a given star has sufficient velocity to escape the cluster. While this method can be reliable, it suffers because the clusters are so far away, even though the stars could be moving at hundreds of kilometers per second, it takes long periods of time to detect it.

Instead, the astronomers in these studies search for runaway stars by the effects they have on the local environment. Since young clusters contain large amounts of gas and dust, stars plowing through it will create bow shocks, similar to those a boat makes in the ocean. Taking advantage of this, the team searched the Eagle Nebula cluster for signs of bow shocks from these stars. Searching images from several studies, the team found three such bow shocks. The same method was used in a second study, this time analyzing a lesser known cluster and nebula in Scorpius, NGC 6357. This survey turned up seven bow shocks of stars escaping the region.

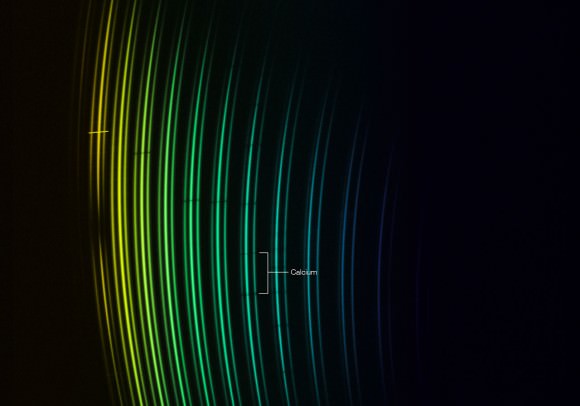

In both studies, the team analyzed the spectral types of the stars which would indicate their mass. Simulations of nebulae suggested that the majority of ejected stars are given their initial kick as they have a close pass to the center of a cluster where the density is the highest. Studies of clusters have shown that their centers are often dominated by massive O and B spectral type stars which would mean that such stars would be preferentially ejected. These two studies have helped to confirm that prediction as all of the stars discovered to have bow shocks were massive stars in this range.

While this method is able to find runaway stars, the authors note that it is an incomplete survey. Some stars may have sufficient velocity to escape, but still fall under the local sound speed in the nebula which would prevent them from creating a bow shock. As such, calculations have predicted that roughly 20% of escaping stars should create detectable bow shocks.

Understanding this mechanism is important because it is expected to play the dominant role in the evolution of the mass distribution of clusters early in their life. An alternative method of ejection involves stars in a binary orbit. If one star becomes a supernova, the sudden mass loss suddenly decreases the gravitational force holding the second star in orbit, allowing it to fly away. However, this method requires that a cluster at least be old enough for stars to have evolved to the point they explode as supernova, delaying this mechanism’s importance until at least that point and allowing the gravitational sling-shot effects to dominate early on.