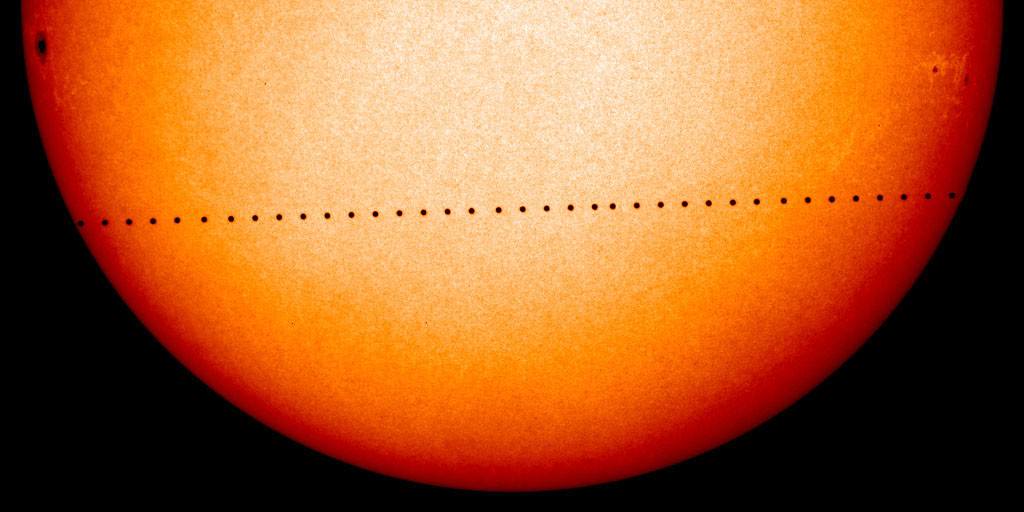

Be sure to mark your calendar for May 9. On that day, the Solar System’s most elusive planet will pass directly in front of the Sun. The special event, called a transit, happens infrequently. The last Mercury transit occurred more than 10 years ago, so many of us can’t wait for this next. Remember how cool it was to see Venus transit the Sun in 2008 and again in 2012? The views will be similar with one big difference: Mercury’s a lot smaller and farther away than Venus, so you’ll need a telescope. Not a big scope, but something that magnifies at least 30x. Mercury will span just 10 arc seconds, making it only a sixth as big as Venus.

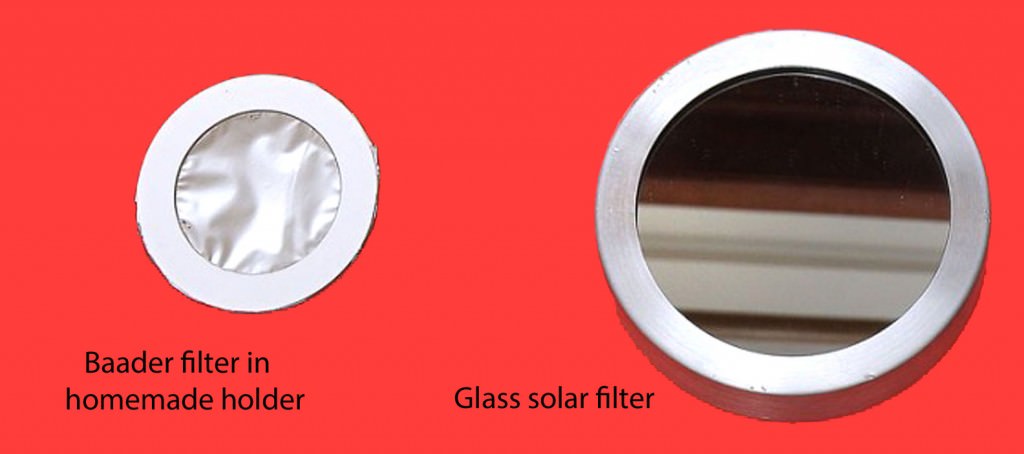

That also means you’ll need a solar filter for your telescope. If you’ve put off buying one, now’s the time to plunk down that credit card. Safe, quality filters are available from many sources including Orion Telescopes, Thousand Oaks Optical, Kendrick Astro Instruments and Amazon.com.

If I might make a suggestion, consider buying a sheet of Baader AstroSolar aluminized polyester film and cutting it to size to make your own filter. Although the film’s crinkly texture might make you think it’s flimsy or of poor optical quality, don’t be deceived by appearances.

The material yields both excellent contrast and a pleasing neutral-colored solar image. You can purchase any of several different-sized films to suit your needs either from Astro-Physics or on Amazon.com. Prices range from $40-90.

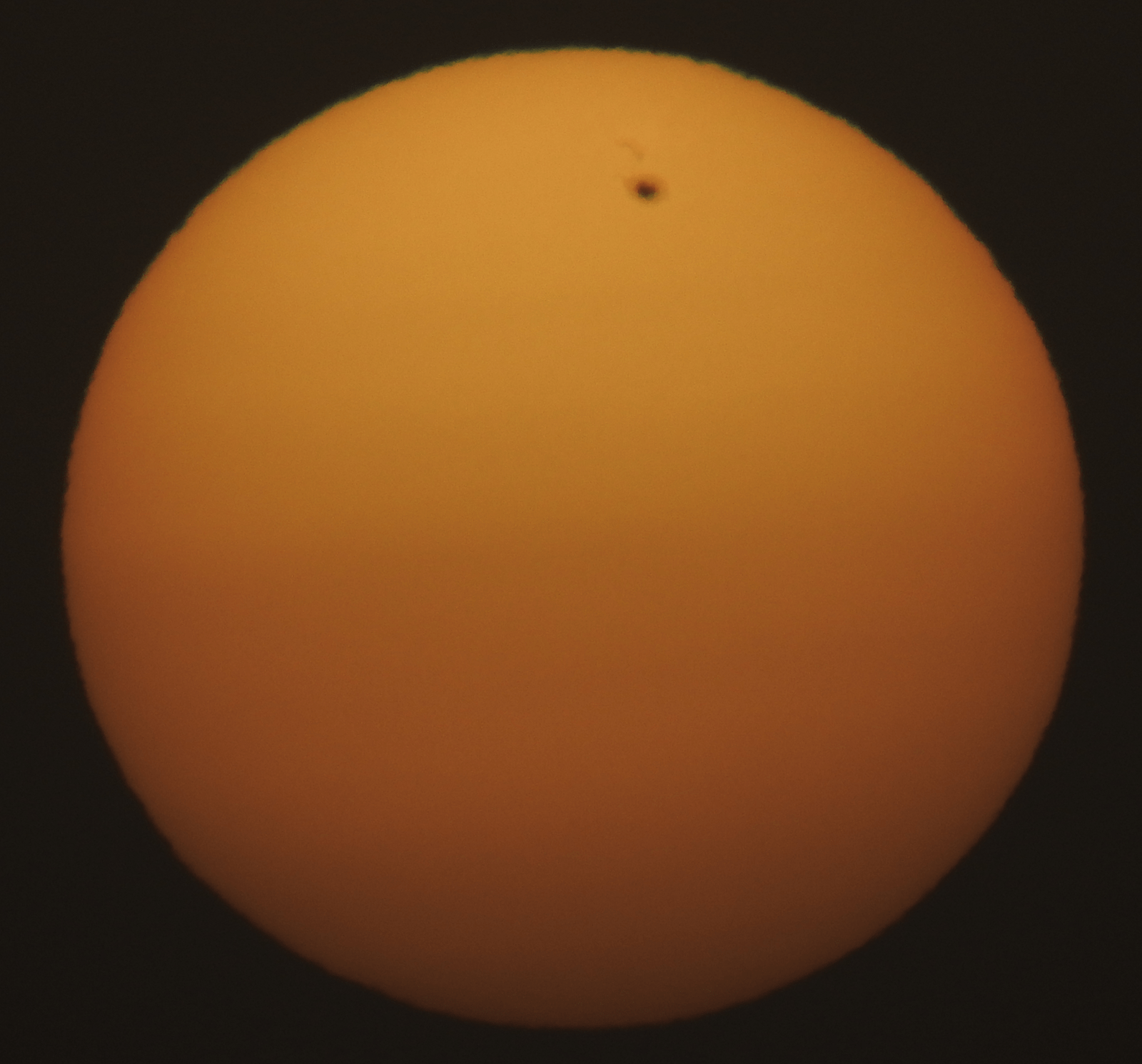

Nov. 8, 2006 Transit of Mercury by Dave Kodama

With filter material in hand, just follow these instructions to make your own, snug-fitting telescopic solar filter. Even I can do it, and I kid you not that I’m a total klutz when it comes to building things. If for whatever reason you can’t get a filter, go to Plan B. Put a low power eyepiece in your scope and project an image of the Sun onto a sheet of white paper a foot or two behind the eyepiece.

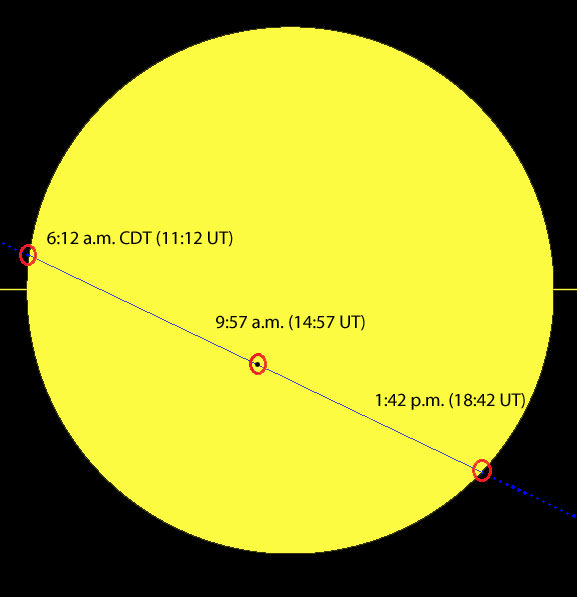

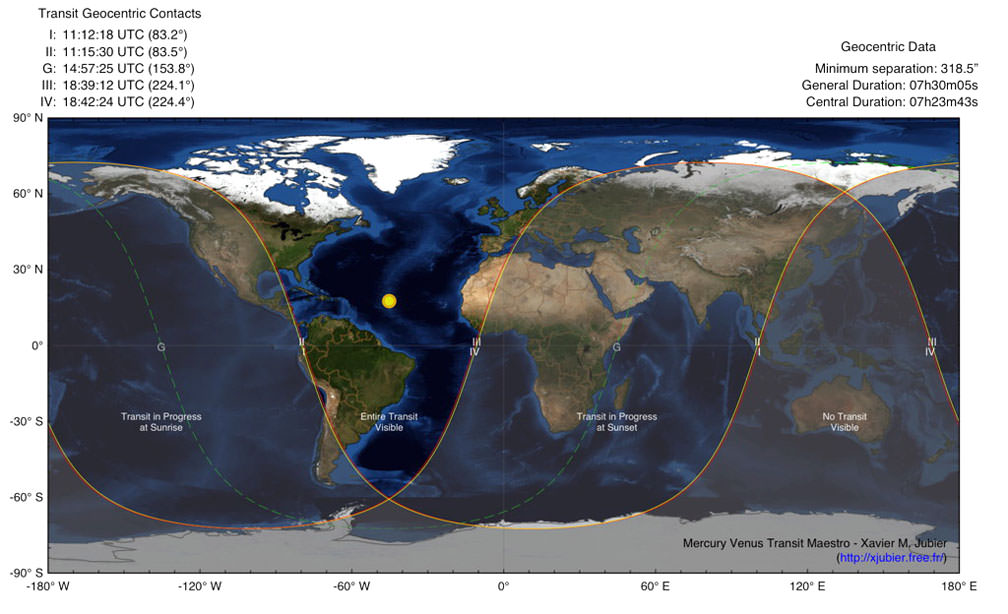

Since May 9th is a Monday, I’ve a hunch a few of you will be taking the day off. If you can’t, pack a telescope and set it up during lunch hour to share the view with your colleagues. Mercury will spend a leisurely 7 1/2 hours slowly crawling across the Sun’s face, traveling from east to west. The entire transit will be visible across the eastern half of the U.S., most of South America, eastern and central Canada, western Africa and much of western Europe. For the western U.S., Alaska and Hawaii the Sun will rise with the transit already in progress.

| Time Zone | Eastern (EDT) | Central (CDT) | Mountain (MDT) | Pacific (PDT) |

| Transit start | 7:12 a.m. | 6:12 a.m. | 5:12 a.m. | Not visible |

| Mid-transit | 10:57 a.m. | 9:57 a.m. | 8:57 a.m. | 7:57 a.m. |

| Transit end | 2:42 p.m. | 1:42 p.m. | 12:42 p.m. | 11:42 a.m. |

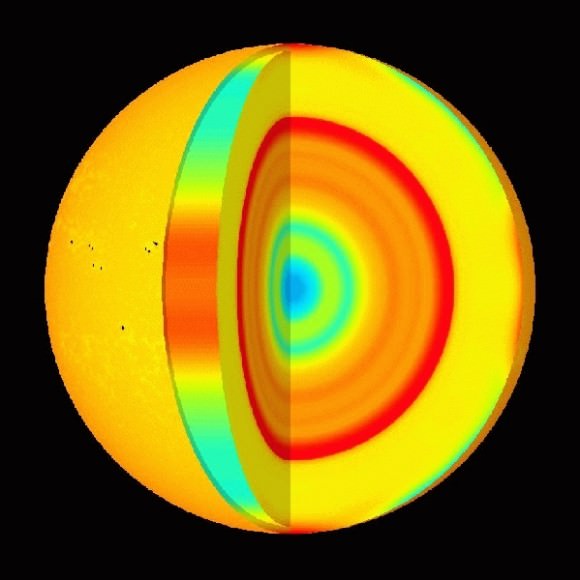

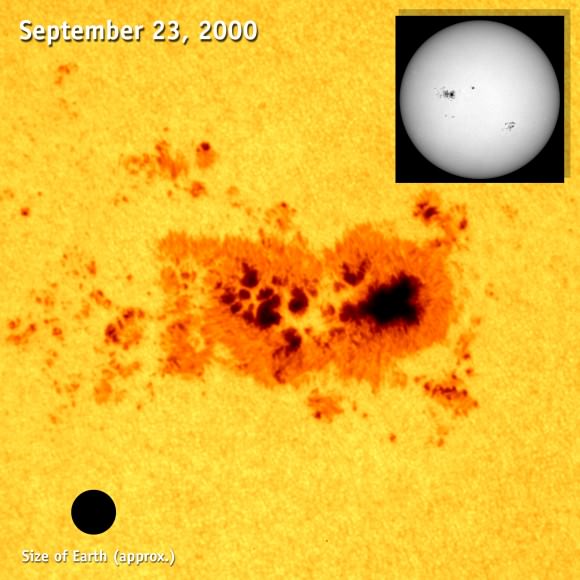

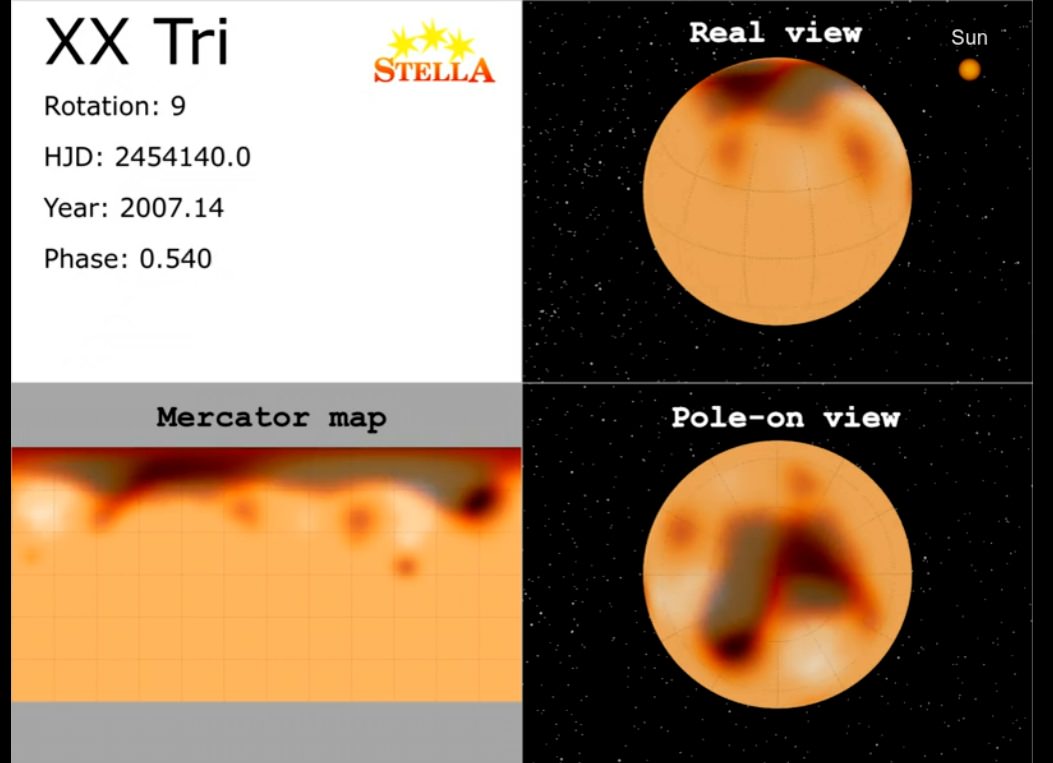

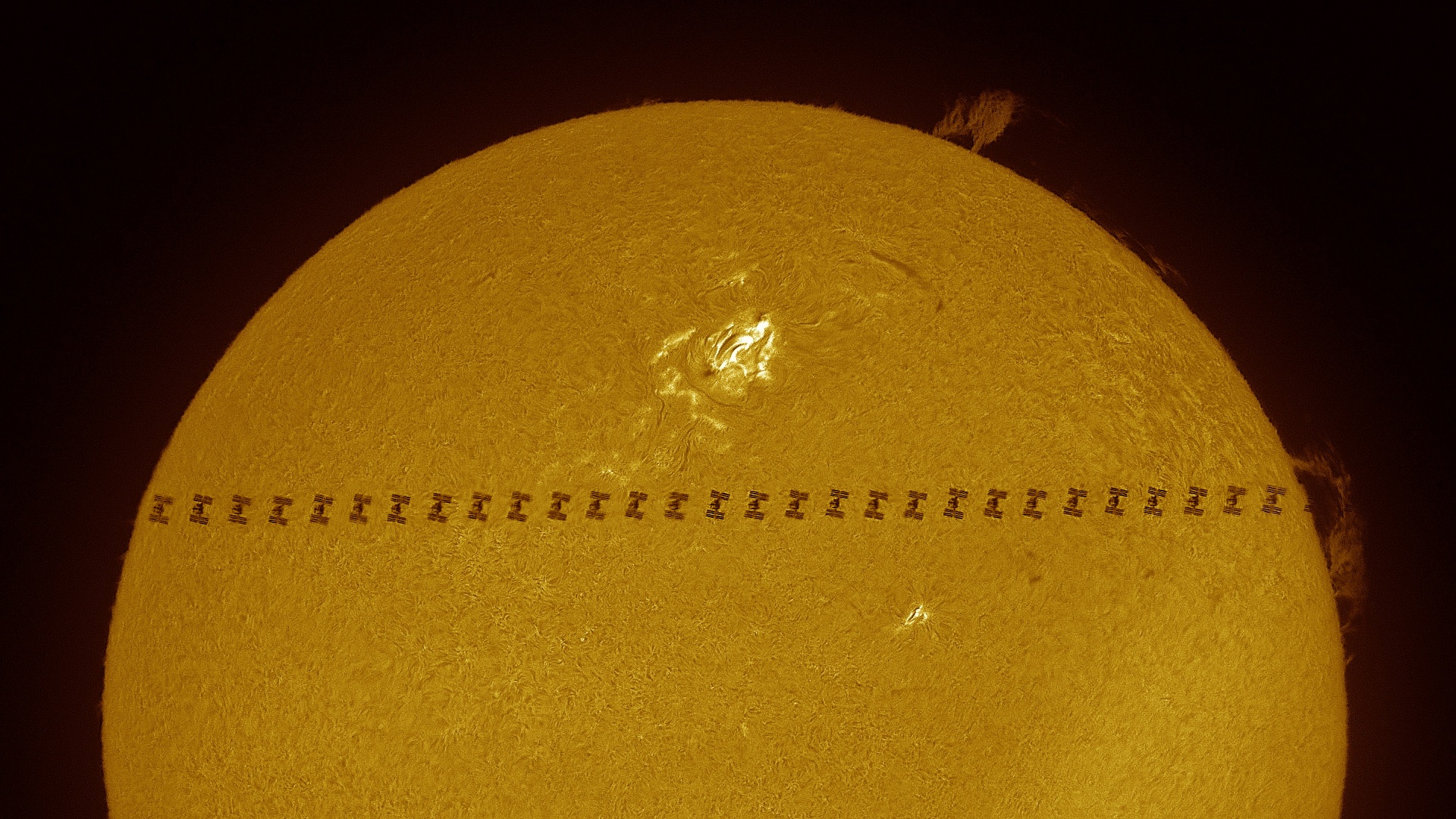

At first glance, the planet might look like a small sunspot, but if you look closely, you’ll see it’s a small, perfectly circular black dot compared to the out-of-round sunspots which also possess the classic two-part umbra-penumbra structure. Oh yes, it also moves. Slowly to be sure, but much faster than a typical sunspot which takes nearly two weeks to cross the Sun’s face. With a little luck, a few sunspots will be in view during transit time; compared to midnight Mercury their “black” umbral cores will look deep brown.

I want to alert you to four key times to have your eye glued to the telescope; all occur during the 3 minutes and 12 seconds when Mercury enters and exits the Sun. They’re listed below in Universal Time or UT. To convert UT to EDT, subtract 4 hours; CDT 5 hours; MDT 6 hours, PDT 7 hours, AKDT 8 hours and HST 10 hours.

First contact (11:12 UT): Watch for the first hint of Mercury’s globe biting into the Sun just south of the due east point on along the edge of disk’s edge. It’s always a thrill to see an astronomical event forecast years ago happen at precisely the predicted time.

Second contact (11:15 UT): Three minutes and 12 seconds later, the planet’s trailing edge touches the inner limb of the Sun at second contact. Does the planet separate cleanly from the solar limb or briefly remain “connected” by a narrow, black “line”, giving the silhouette a drop-shaped appearance?

This “black drop effect” is caused primarily by diffraction, the bending and interfering of light waves when they pass through the narrow gap between Mercury and the Sun’s edge. You can replicate the effect by bringing your thumb and index finger closer and closer together against a bright backdrop. Immediately before they touch, a black arc will fill the gap between them.

Third contact (18:39 UT): A minute or less before Mercury’s leading edge touches the opposite limb of the Sun at third contact, watch for the black drop effect to return.

Fourth contact (18:42 UT): The moment the last silhouetted speck of Mercury exits the Sun. Don’t forget to mark your calendar for November 11, 2019, date of the next transit, which also favors observers in the Americas and Europe. After that one, the next won’t happen till 2032.

Other interesting visuals to keep an eye out for is a bright ring or aureole that sometimes appears around the planet caused when our brain exaggerates the contrast of an object against a backdrop of a different brightness. Another spurious optical-brain effect keen-eyed observers can watch for is a central bright spot inside Mercury’s black disk. Use high power to get the best views of these obscure but fascinating phenomena seen by many observers during Mercury transits.

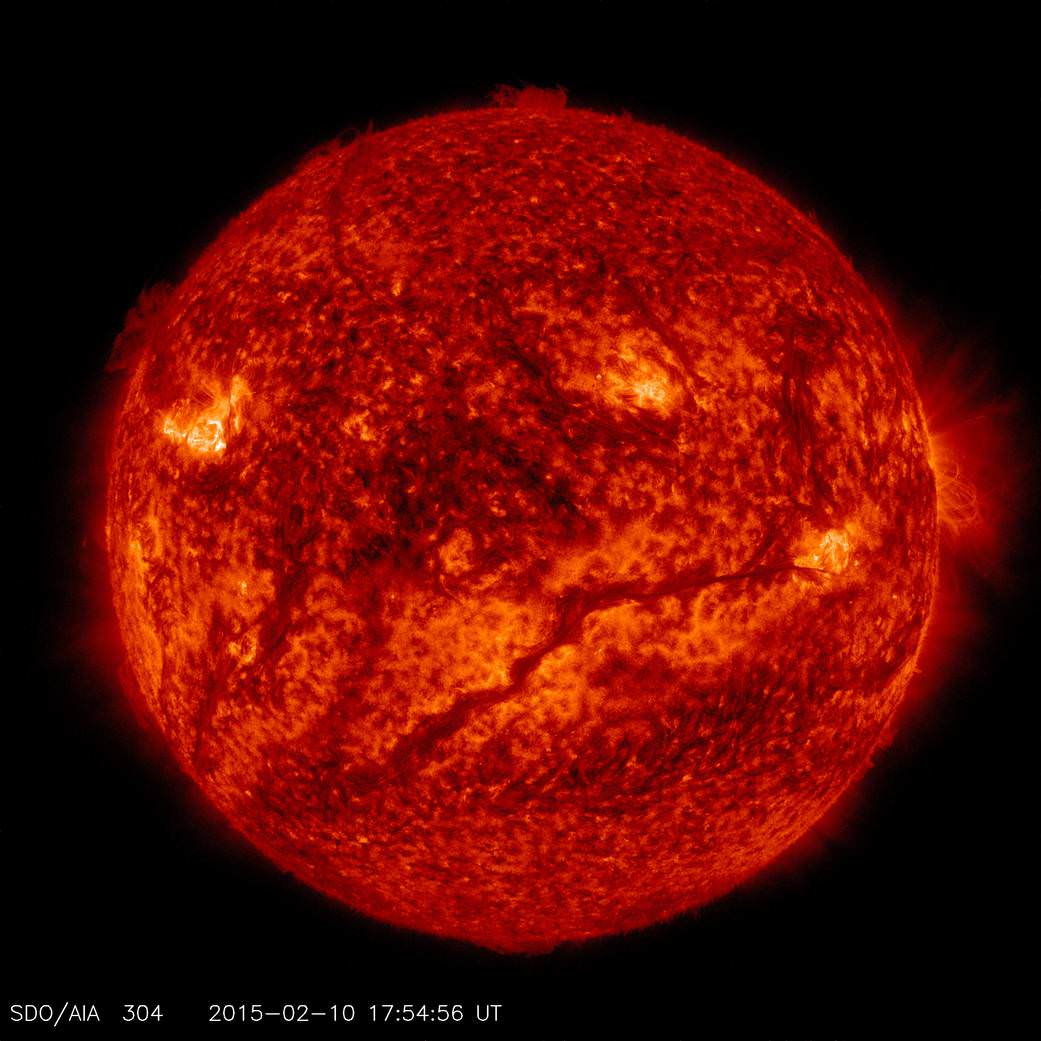

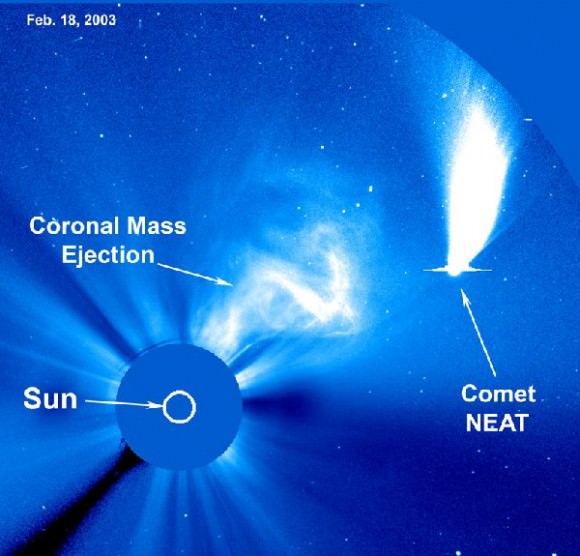

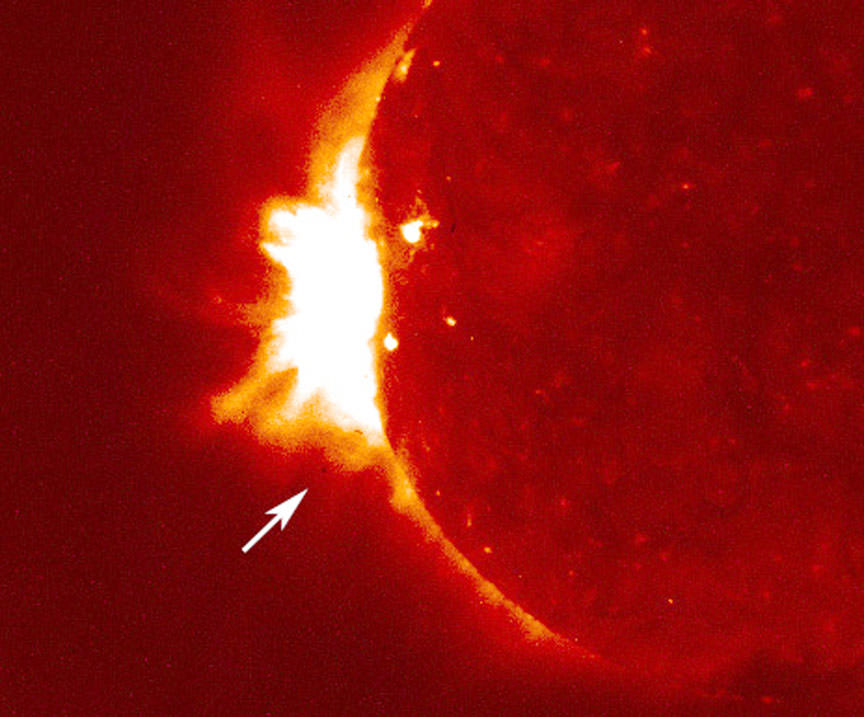

While I’ve been talking all “white light” observation, the proliferation of relatively inexpensive and portable hydrogen-alpha telescopes in recent years makes them another viewing option with intriguing possibilities. These instruments show solar phenomena beyond the Sun’s limb, including the flaming prominences normally seen only during a total eclipse. That makes it possible to glimpse Mercury minutes in advance of the transit (or minutes after transit end) silhouetted against a prominence or nudging into the rim furry ring of spicules surrounding the outer limb. Wow!

One final note. Be careful never to look directly at the Sun even for a moment during the transit. Keep your eyes safe! When aiming a telescope, the safest and easiest way to center the Sun in the field of view is to shift the scope up and down and back and forth until the shadow the tube casts on the ground is shortest. Try it.

I hope the weather gods smile on you on May 9, but it they don’t or if you live where the transit won’t be visible, Italian astrophysicist Gianluca Masi will stream it live on his Virtual Telescope website starting at 11:00 UT (6 a.m CDT).