As the northern hemisphere enters the hazy days of summer, thunderstorms will freckle many of our nights and days. What causes these sudden bursts of light that flash through the sky? Previous research showed that one cause is cosmic rays from space, generated by supernovas. But a new paper shows that something much closer and powerful is also responsible: solar wind from our own Sun.

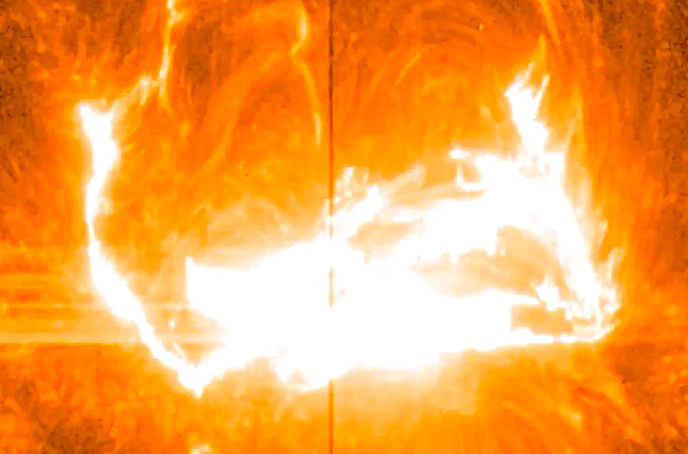

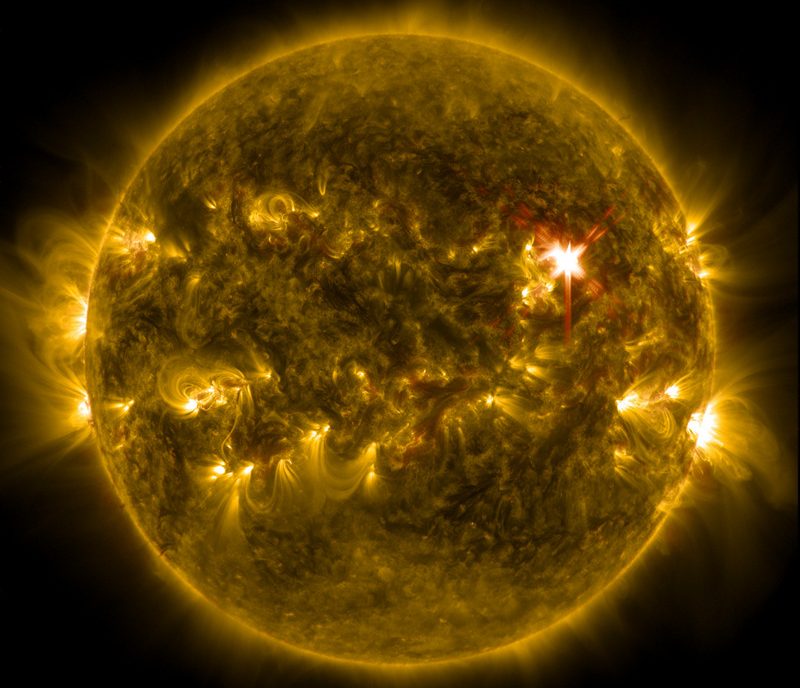

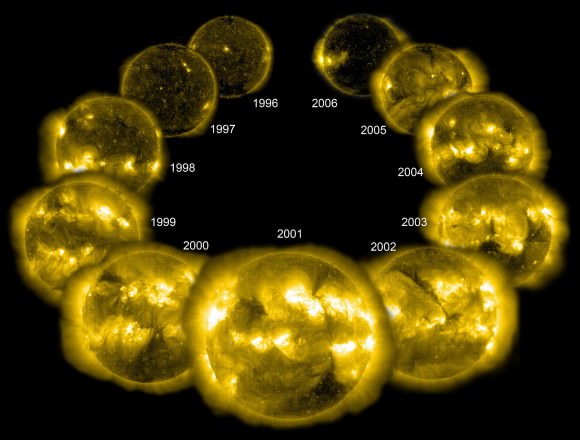

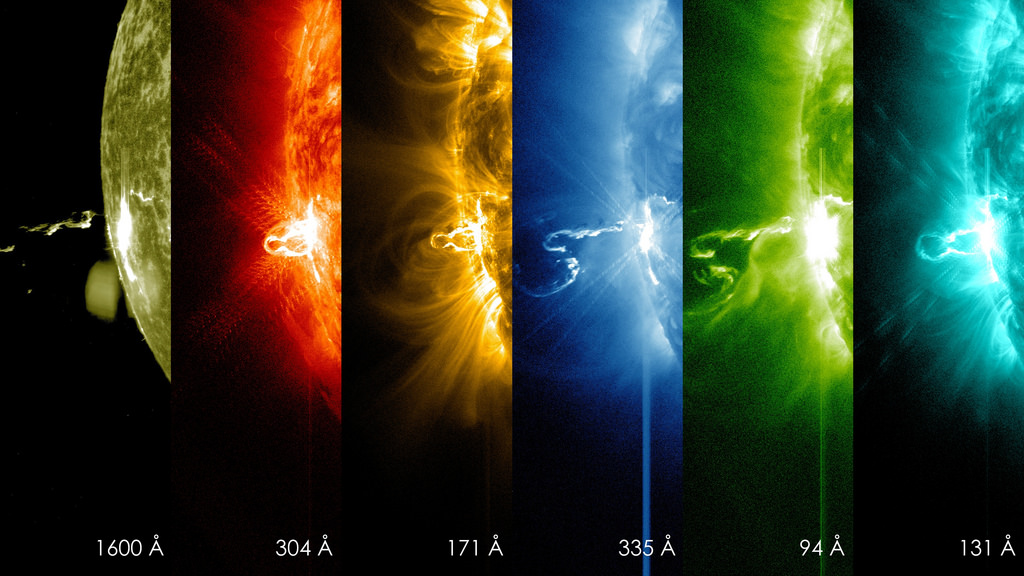

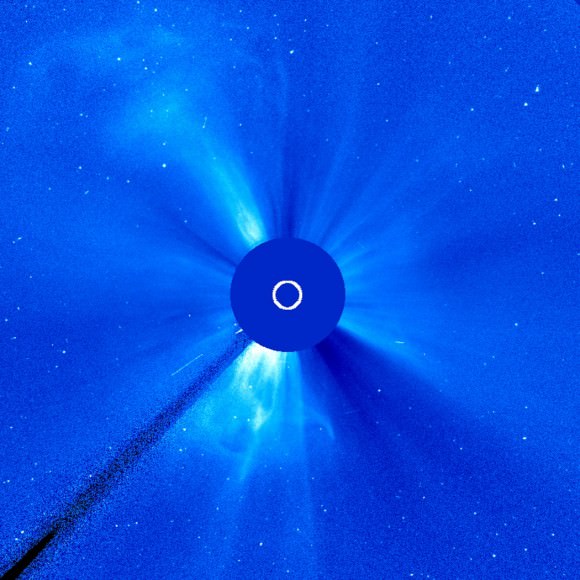

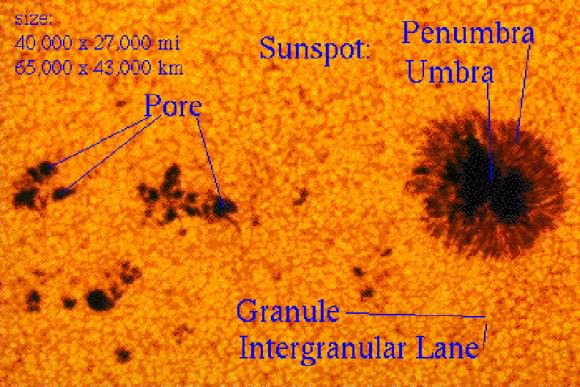

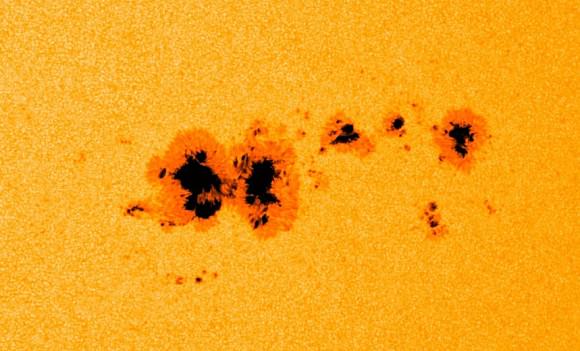

First, a quick primer on what the solar wind is. It’s a continuous stream of particles from the Sun, and it tends to pick up when the Sun emits solar flares. These flares are more frequent when sunspots are in greater numbers on the star’s surface, which happens when the Sun’s magnetic activity increases. The Sun’s activity falls and rises on an 11-year cycle, and 2014 happens to be close to the peak of one of those cycles.

“Our main result,” said lead author Chris Scott (of the University of Reading) in a statement, “is that we have found evidence that high-speed solar wind streams can increase lightning rates. This may be an actual increase in lightning or an increase in the magnitude of lightning, lifting it above the detection threshold of measurement instruments.”

The researchers discovered “a substantial and significant increase in lightning rates” for up to 40 days after solar winds hit Earth’s atmosphere. The reasons behind this are still poorly understood, but the researchers say this could be because the air’s electrical charge changes as the particles (which are themselves electrically charged) hit the atmosphere.

If this is proven, this could give a new nuance to weather forecasters who could incorporate information about solar wind streams that are being watched by spacecraft. This stream of particles would change with the sun’s 27-day rotation, and researchers hope this could improve long-range forecasts.

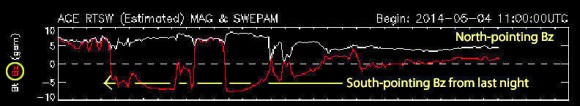

The study is based on UK Met Office lightning strike data in the United Kingdom between 2000 and 2005, more specifically anything that happened within 500 kilometers (310 miles) of central England. They also used data from NASA’s Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE), a spacecraft that examines the solar wind.

After each event, the researchers uncovered an average of 422 lightning strikes in the United Kingdom in the next 40 days, compared to an average of 321 lightning strikes in between these events. (The peak was about 12 to 18 days after an event.)

The researchers pointed out that the magnetic field of Earth does deflect many of these particles, but in the cases observed the particles would have been energetic enough to move into “cloud-forming regions” of the Earth’s atmosphere.

“We propose that these particles, while not having sufficient energies to reach the ground and be detected there, nevertheless electrify the atmosphere as they collide with it, altering the electrical properties of the air and thus influencing the rate or intensity at which lightning occurs,” Scott stated.

You can read more about the paper in Environmental Research Letters.

Source: IOP Publishing