A little history of sun-watching and science from our friends at the Solar Dynamics Observatory.

First Ever Whole Sun View .. Coming Soon from STEREO

“For the first time in the history of humankind we will be able to see the front and the far side of the Sun … Simultaneously,” Madhulika Guhathakurta told Universe Today. Guhathakurta is the STEREO Program Scientist at NASA HQ.

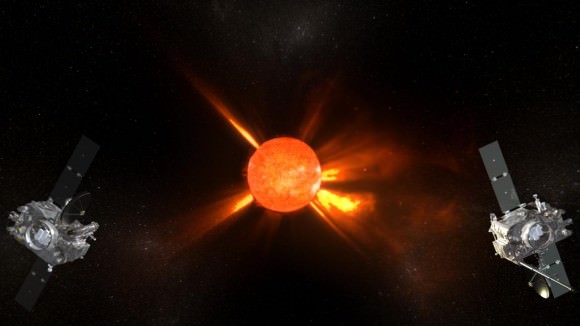

Courtesy of NASA’s solar duo of STEREO spacecraft.

And the noteworthy event is timed to coincide just perfectly with ‘Super Bowl SUNday’ – Exactly one week from today on Feb. 6 during Super Bowl XLV !

“This will be the first time we can see the entire Sun at one time,” said Dean Pesnell, NASA Solar Astrophysicist in an interview for Universe Today. Pesnell is the Project Scientist for NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory at the NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, MD.

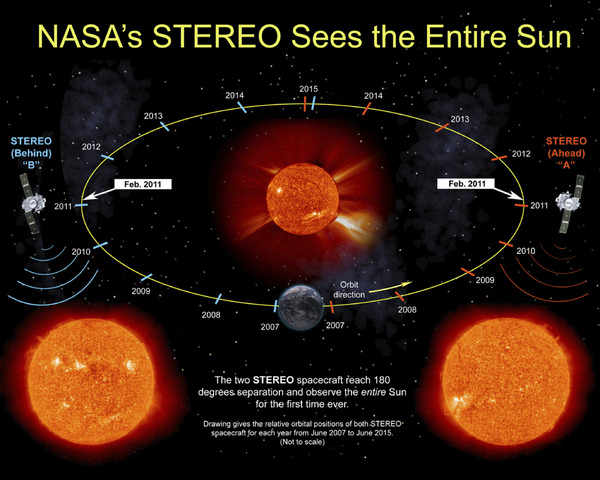

This remarkable milestone will be achieved when NASA’s two STEREO spacecraft reach position 180 degrees separate on opposite sides of the Sun on Sunday, Feb. 6, 2011 and can observe the entire 360 degrees of the Sun.

“We are going to celebrate by having a football game that night!” Pesnell added in jest.

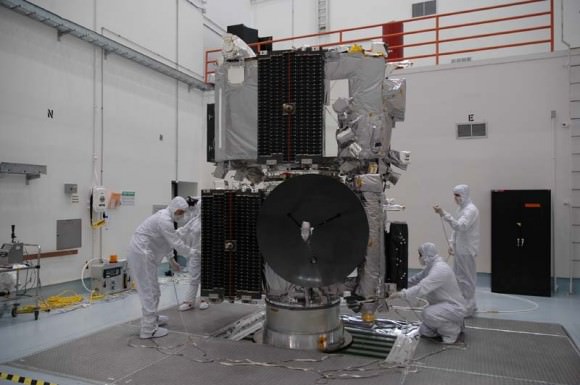

The nearly identical STEREO spacecraft – dubbed STEREO Ahead and STEREO Behind – are orbiting the sun and providing a more complete picture of the Suns environment with each passing day. One probe follows Earth around the sun; the other one leads the Earth.

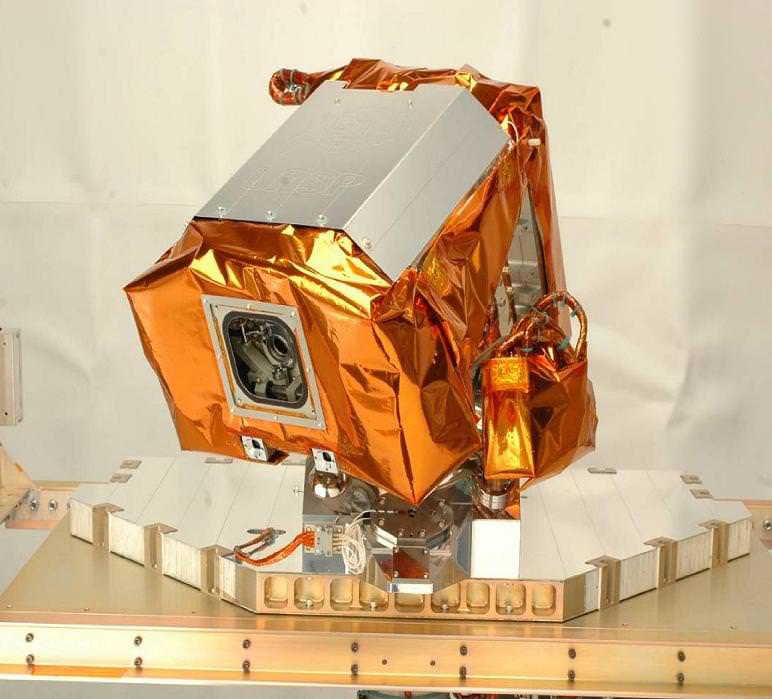

STEREO is the acronym for Solar TErrestrial RElations Observatory. Their mission is to provide the very first, 3-D “stereo” images of the sun to study the nature of coronal mass ejections.

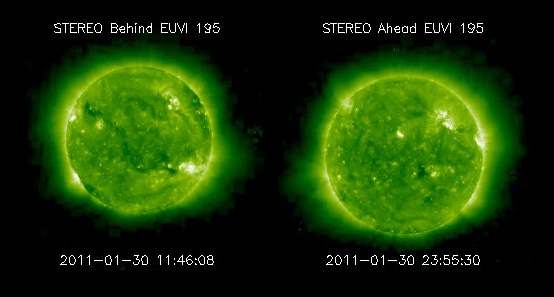

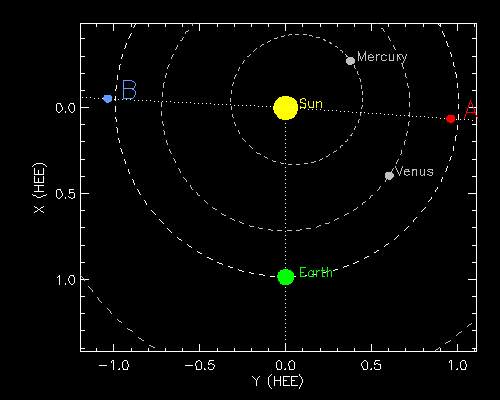

Today, (Jan 30) the twin STEREO spacecraft are 179.1 degrees apart and about 90 degrees from Earth, and thus virtually at the midpoint to the back of the sun. See the orbital location graphics above and below.

Both probes were flung into space some four years ago and have been hurtling towards this history making date and location ever since. The wedge of unseen solar territory has been declining.

As the STEREO probes continue flying around to the back side of the sun, the wedge of unseen solar territory on the near side will be increasing and the SDO solar probe will play a vital gap filling role.

“SDO provides the front side view of the sun with exquisite details and very fast time resolution,” Gutharka told me. For the next 8 years, when combined with SDO data, the full solar sphere will still be visible.

For the past 4 years, the two STEREO spacecraft have been moving away from the Earth and gaining a more complete picture of the sun. On February 9, 2011, NASA will hold a press conference to reveal the first ever images of the entire sun and discuss the importance of seeing all of our dynamic star.

Credit: NASA

The solar probes were launched together aboard a Delta II rocket from Launch Complex 17B at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS) in Florida on October 25, 2006. See Launch Video and Photos below.

Whole Solar Sphere A Goldmine for Science

I asked Pesnell and Guhathakurta to explain why this first ever whole Sun view is a significant scientific milestone.

“Until now there has always been an unseen part of the Sun,” Pesnell explained. “Although that unseen part has always rotated into view within a week or two, a global model must include all of the Sun to understand where the magnetic field goes through the surface.”

“Also, from the Earth we can see only one pole of the Sun at a time, while with STEREO we can see both poles at the same time.

“The next few years of overlapping coronal images will be a goldmine of information for predicting space weather at the Earth and understanding of how the Sun works. It is like getting the GOES images of the Earth for the first time. We haven’t missed a hurricane since, and now we won’t miss an active region on the Sun,” said Pesnell.

How will the science data collected be used to understand the sun and its magnetic field?

“Coronal loops trace out the magnetic field in the corona,” Pesnell elaborated. “Understanding how that magnetic field changes requires seeing where on the surface each loop starts and stops.”

Why is it important to image the entire Sun ?

“Once images of the entire Sun are available we can model the entire magnetic field of the Sun. This has become quite important as we are using STEREO and SDO to study how the entire magnetic field of the Sun reacts to the explosions of even small flares.”

“By seeing both poles we should be able to understand why the polar magnetic field is a good predictor of solar activity,” said Pesnell.

“Seeing both sides will help scientists make more accurate maps of global coronal magnetic field and topology as well as better forecasting of active regions – areas that produce solar storms – as they rotate on to the front side. Simultaneous observations with STEREO and SDO will help us study the sun as a complete whole and greatly help in studying the magnetic connectivity on the sun and sympathetic flares, ” Guhathakurta amplified.

Watch a solar rotation animation here combining EUVI and SDO/AIA:

What is the role and contribution of NASA’s SDO mission and how will SDO observations be coordinated with STEREO?

“As the STEREO spacecraft drift around the Sun, SDO will fill in the gap on the near of the Sun,” explained Pesnell. “For the next 4 or more years we will watch the increase in sunspots we call Solar Cycle 24 from all sides of the Sun. SDO has made sure we are not doing calibration maneuvers for a few days around February 6.”

“On Feb 6th we will view 100% of the sun,” said Guhathakurta.

At a press conference on Feb. 9, 2011, NASA scientists will reveal something that no one has even seen – The first ever images of ‘The Entire Sun’. All 360 degrees

Watch the briefing on NASA TV at 2 PM EST

More about the SDO mission and SDO science

and Coronal holes from STEREO and SDO here

“3D Sun”

A STEREO Movie in Digital and IMAX was released in 2007

Watch the way cool 3D IMAX trailer below

STEREO spacecraft location map

Caption: Positions of STEREO A and B for 31-Jan-2011 05:00 UT. The STEREO spacecraft are 179.2 degrees apart and about 90 degrees from Earth on Jan. 31, 2011. This figure plots the current positions of the STEREO Ahead (red) and Behind (blue) spacecraft relative to the Sun (yellow) and Earth (green). The dotted lines show the angular displacement from the Sun. Units are in A.U. (Astronomical Units). Credit: NASA

STEREO Launch Video

Launch Video Caption: The Delta II rocket lights the evening sky as STEREO heads into space on October 25, 2006 at 8:52 p.m. The Delta II rocket lights the evening sky as STEREO heads into space. STEREO (Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory) is a multi-year mission using two nearly identical observatories, one ahead of Earth in its orbit and the other trailing behind. The duo will provide 3-D measurements of the sun and its flow of energy, enabling scientists to study the nature of coronal mass ejections and why they happen.

More STEREO Cleanroom and Launch photos from nasatech.net here

More about the SDO mission and SDO science

and Coronal holes from STEREO and SDO here

“3D Sun”

A STEREO Movie in Digital and IMAX was released in 2007

Watch the way cool 3D trailer here – Trailer narrated by NASA’s Madhulika Guhathakurta

— be sure to grab hold of your Red-Cyan Glasses

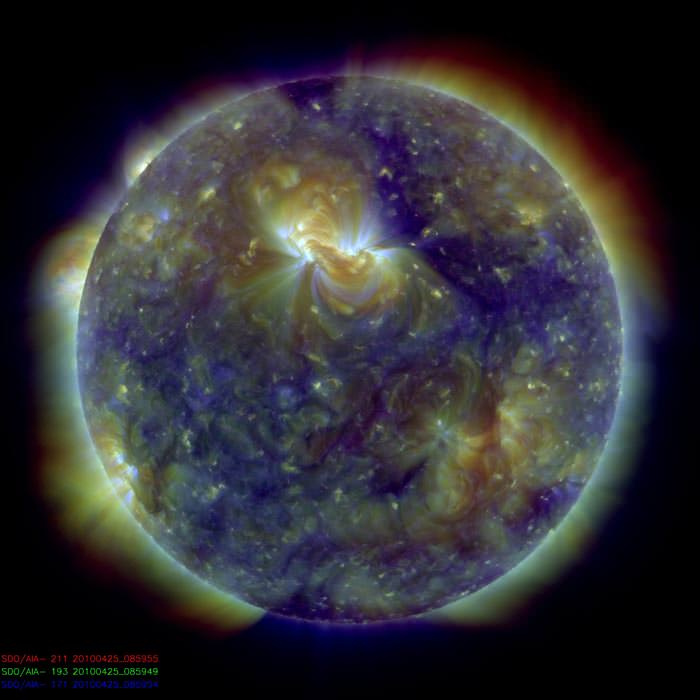

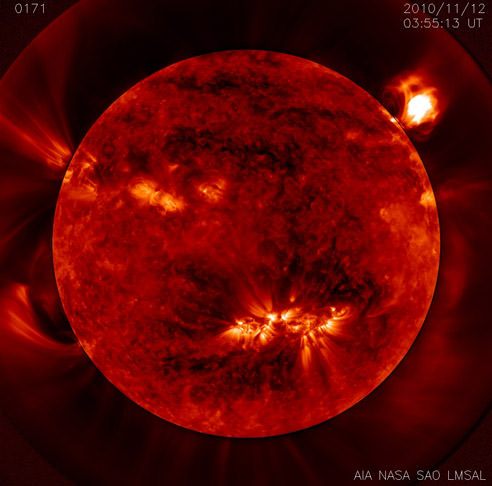

Double Explosions on the Sun Today

The Sun had a fit and popped off two large events at once early today, Jan. 28, 2011. A filament on the left side became unstable and erupted, while an M-1 flare (mid-sized) and a coronal mass ejection on the right blasted into space. Neither event was headed towards Earth. This SDO movie, which is from Jan. 26-28, 2011, shows several other flashes and bursting from the active region on the right as well.

If you remember, in December, solar physicists released their findings that near-synchronous explosions in the solar atmosphere – sometimes millions of kilometers apart – can be related.

You can see another view of the events as seen by the SOHO spacecraft below, and another version of the SDO data.

Continue reading “Double Explosions on the Sun Today”

Sun Plays A Major Role In Climate Change

[/caption]

It’s not often I voice my opinion on climate change without sounding like a tree-hugger or a total kook. However, in this circumstance I had an opportunity to read about some findings that hit home with my own personal thoughts and I figured you might like to know, too.

According to the latest American Astronomical Society Press Release, “Scientists have taken a major step toward accurately determining the amount of energy that the Sun provides to Earth, and how variations in that energy may contribute to climate change. In a new study of laboratory and satellite data, researchers report a lower value of that energy, known as total solar irradiance, than previously measured and demonstrate that the satellite instrument that made the measurement — which has a new optical design and was calibrated in a new way — has significantly improved the accuracy and consistency of such measurements. The new findings give confidence, the researchers say, that other, newer satellites expected to launch starting early this year will measure total solar irradiance with adequate repeatability — and with little enough uncertainty — to help resolve the long-standing question of how significant a contributor solar fluctuations are to the rising average global temperature of the planet.

“Improved accuracies and stabilities in the long-term total solar irradiance record mean improved estimates of the Sun’s influence on Earth’s climate,” said Greg Kopp of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) of the University of Colorado Boulder. Kopp, who led the study, and Judith Lean of the Naval Research Laboratory, in Washington, D.C., published their findings today in Geophysical Research Letters, a journal of the American Geophysical Union. The new work will help advance scientists’ ability to understand the contribution of natural versus anthropogenic causes of climate change, the scientists said. That’s because the research improves the accuracy of the continuous, 32-year record of total solar irradiance, or TSI. Energy from the Sun is the primary energy input driving Earth’s climate, which scientific consensus indicates has been warming since the Industrial Revolution.

Lean specializes in the effects of the Sun on climate and space weather. She said, “Scientists estimating Earth’s climate sensitivities need accurate and stable solar irradiance records to know exactly how much warming to attribute to changes in the Sun’s output, versus anthropogenic or other natural forcings.” The new, lower TSI value was measured by the LASP-built Total Irradiance Monitor (TIM) instrument on the NASA Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) spacecraft. Tests at a new calibration facility at LASP verify the lower TSI value. The ground- based calibration facility enables scientists to validate their instruments under on-orbit conditions against a reference standard calibrated by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Before the development of the calibration facility, solar irradiance instruments would frequently return different measurements from each other, depending on their calibration. To maintain a long-term record of the Sun’s output through time, scientists had to rely on overlapping measurements that allowed them to intercalibrate among instruments.

Kopp said, “The calibration facility indicates that the TIM is producing the most accurate total solar irradiance results to date, providing a baseline value that allows us to make the entire 32-year record more accurate. This baseline value will also help ensure that we can maintain this important climate data record for years into the future, reducing the risks from a potential gap in spacecraft measurements.” Lean said, “We are eager to see how this lower irradiance value affects global climate models, which use various parameters to reproduce current climate: incoming solar radiation is a decisive factor. An improved and extended solar data record will make it easier for us to understand how fluctuations in the Sun’s energy output over time affect temperatures, and how Earth’s climate responds to radiative forcing.” Lean’s model, which is now adjusted to the new lower absolute TSI values, reproduces with high fidelity the TSI variations that TIM observes and indicates that solar irradiance levels during the recent prolonged solar minimum period were likely comparable to levels in past solar minima. Using this model, Lean estimates that solar variability produces about 0.1 degree Celsius (0.18 degree Fahrenheit) global warming during the 11-year solar cycle, but is likely not the main cause of global warming in the past three decades.”

I think the new findngs are awesome. For one, we really haven’t been studying our weather with any great accuracy or scientific instruments for that long – only about 5 decades. For those of us who enjoy viewing sunspots, you also might have noticed that when sunspot activity is high, it really does seem to affect our weather – especially cloud cover. Global warming is real, and there is no doubt that mankind has contributed to it. However, take solar findings very much to heart because my opinion is the Sun plays a more important role in our climate than we could have ever dreamed possible.

Original Source: American Geophysical Union – Image Courtesy of NASA

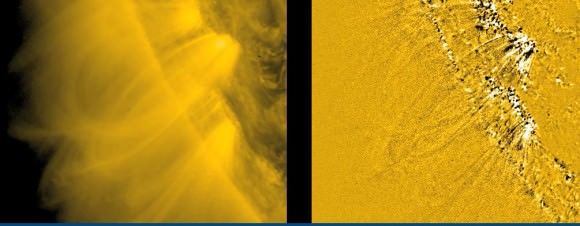

Previously Unseen Super-Hot Plasma Jets Heat the Sun’s Corona

[/caption]

The mystery of the Sun’s corona may finally be solved. For years researchers have known – and wondered why – the Sun’s outer atmosphere, or corona, is considerably hotter than its surface. But now, using the combined visual powers of NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory and Japan’s Hinode satellite, scientists have made direct observations of jets of plasma shooting off the Sun’s surface, heating the corona to millions of degrees. The existence of these small, narrow jets of plasma, called spicules has long been known, but they had never been directly studied before and were thought to be too cool to have any appreciable heating effect. But a good look with new “eyes” reveals a new kind of spicule that moves energy from the Sun’s interior to create its hot outer atmosphere.

“Heating of spicules to millions of degrees has never been directly observed, so their role in coronal heating had been dismissed as unlikely,” says Bart De Pontieu, the lead author and a solar physicist at LMSAL.

Solar physicst and former Universe Today writer Ian O’Neill (and current Discovery Space producer, and of Astroengine fame) compared the anomaly of the Sun’s atmosphere being hotter than the surface to if the air surrounding a light bulb was a couple of magnitudes hotter than the bulb’s surface. And, he said, you’d want to know why it appears the solar atmosphere is breaking all kinds of thermodynamic laws.

Over the years, experts have proposed a variety of theories, and as De Pontieu said, the spicule theory had been dismissed when it was found spicule plasma did not reach coronal temperatures.

But In 2007, De Pontieu and a group of researchers identified a new class of spicules that moved much faster and were shorter lived than the traditional spicules. These “Type II” spicules shoot upward at high speeds, often in excess of 60 miles per second (100 kilometers per second), before disappearing. The rapid disappearance of these jets suggested that the plasma they carried might get very hot, but direct observational evidence of this process was missing.

Enter SDO and its Atmospheric Imaging Assembly instrument which launched in February 2010, along with NASA’s Focal Plane Package for the Solar Optical Telescope (SOT) on the Japanese Hinode satellite.

“The high spatial and temporal resolution of the newer instruments was crucial in revealing this previously hidden coronal mass supply,” said Scott McIntosh, a solar physicist at NCAR’s High Altitude Observatory. “Our observations reveal, for the first time, the one-to-one connection between plasma that is heated to millions of degrees kelvin and the spicules that insert this plasma into the corona.”

The spicules are accelerated upward into the solar corona in fountain-like jets at speeds of approximately 31 to 62 miles per second (50 to 100 kilometers per second). The research team says that the majority of the plasma is heated to temperatures between 0.02 and 0.1 million Kelvin, while a small fraction is heated to temperatures above one million Kelvin.

A key step in learning more about the Sun, according to De Pontieu, will be to better understand the interface region between the Sun’s visible surface, or photosphere, and its corona. Another NASA mission, the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS), is scheduled for launch in 2012. IRIS will provide high-fidelity data on the complex processes and enormous contrasts of density, temperature, and magnetic field between the photosphere and corona. Researchers hope this will reveal more about the spicule heating and launch mechanisms.

This research appears in the 07 January issue of Science.

Sources: Science, Astroengine

Spectacular Photos from the Jan. 4 Partial Solar Eclipse

[/caption]

Millions across Earth enjoyed one of nature’s most awesomely spectacular events during today’s (Jan. 4) partial solar eclipse – the first of four set to occur in 2011. And there was nothing partial about it, for those lucky eyewitnesses where it was visible in parts of Europe, Africa and Central Asia. The eclipse reached its maximum, about 85%, in Sweden. See the maximum stunner above – taken despite pessimistic weather forecasts -by Peter Rosen in Stockholm, Sweden, with more photos from the sequence here at spaceweather.com

Probably the most technically amazing feat is the double solar eclipse captured in one image by renowned astrophotographer Theirry Legault – see below – boasting both the ISS and the Moon on the eclipsed sun’s face. Legault had traveled to the deserts of the Sultanate of Oman, near to the capital of Muscat, for this rare spectacle of nature. The ISS was calculated to be visible in a thin strip barely 11 kilometers wide, according to Astronomie Info news. The ISS transit lasted just about 1 second, speeding by at 28,000 km/sec.

See a global compilation of gorgeous eclipse photos here and comment or send us more.

Update 1/6/11: this is a work in progress so please check back again.

New readers photos and eyewitness accounts added below today; as received

Click to enlarge all photos

First up: Double Solar Eclipse by renowned astrophotographer Theirry Legault in Oman

Check out this exciting gallery of images contributed by eclipse watchers from multiple locations around the world, on Flickr

Here is a collection of images and an eyewitness report sent to me by Marco Di Lorenzo, in Pescara, Italy

Marco writes; Pescara is located at 42.467°N and 14.225°E, about in the center of Italy on the Adriatic sea. I chose my location at the new pedestrian bridge because it is a modern structure which offers a nice foreground and also an open, elevated viewpoint. I used a couple of cameras plus a digital video camera. All the cameras were mounted on a tripod.

The weather was cold and the situation didn’t improve in the mid morning. Illumination was comparable to a slightly foggy day. The frigid temperature didn’t encourage people to go out and check. However some people did venture out. Someone asked me some info on eclipses and how to take pictures of it – very hard indeed, especially if you use a cellular phone !

Urijian Poernick sent these photos and description:

“Colorful Solar Eclipse” at Halley Astronomical Observatory, Heesch, The Netherlands

The weather forecast predicted overcast skies with only a few small bright intervals in all parts of The Netherlands. Nevertheless, dozens of members of Halley Astronomical Society and visitors, including many children, challenged the cold winter weather and came together on the flat roof of Halley Astronomical Observatory in The Netherlands.

Due to the clouds and veils it was a very colorful eclipse, with all tints of red and yellow. After twenty minutes the sun and the moon disappeared behind the overcast skies again and they didn’t come back before the end of the eclipse (9:39 UT).

During this short period everyone could watch the eclipse through the telescope and we were all enthusiastic. It was a beautiful spectacle! www.sterrenwachthalley.nl

Gianluca Masi is the National Coordinator of Astronomers Without Borders in Italy and captured this pair of photos from partially overcast Rome, Italy. The clouds contributed to make for a delightfully smoky eclipsed sun

Edwin van Schijndel sent me this report from the Netherlands:

I made some pictures in the southwest of the Netherlands. The weather conditions were not so good in the early morning, most places were covered by clouds so we decided to move about 70 miles to the southwest from our hometown. Finally we stopped not far from the city of Bergen op Zoom and were able to see sunrise while most of the sun was covered. It was splendid!

Unfortunately there came more clouds so the rising sun disappeared and we drove 20 miles to the north just before Rotterdam and the sky was more clear at this place. Again we took some pictures but the maximum covering of the sun had been a few minutes before. After all this wasn’t really a pity, we were very lucky to have seen the rising of the sun and be able to make some nice pictures of the partial eclipse. Many people in the Netherlands saw less or even nothing.

Send us or comment more solar eclipse photos to post here. ken : [kremerken at yahoo.com]

Look here for some photos from the recent total lunar eclipse on Dec. 21, 2010

Read a great preview about the eclipse by Tammy Plotner

…………………..

More Readers Photos and Eyewitness Accounts. Beautiful, Thanks ! ken

Story and Photos sent me by Stefano De Rosa. Turin, Italy

Early in the morning, I moved to a site close to Turin (Italy) where the forecast was not so bad as in my city to try to observe and photograph the partial solar eclipse. Unfortunately, when I arrived it was cloudy and foggy and so decided to go back home. Technical details: Canon Eos 1000d, F/22; 150-500mm lens @ 500mm; ISO. 1/1600 sec

Suddenly, as I was sadly driving on the motorway, close to the city of Alessandria, noticed a little break on the clouds from my rearview mirror: I stopped the car and, after a quick set up, managed to capture the crescent Sun!

http://ofpink.wordpress.com

Well, I hope you carefully looked back before hitting the brakes ! – ken

……..

Story and Photos sent me by Roy Keeris, Zeist, The Netherlands

Me and a friend (Casper ter Kuile) wanted to see the eclipse from The Netherlands. If clouds should intervene, we planned to drive a little (max. a couple of hours) to a place with a better chance for a clear sky. During the night we checked weather forecasts and satellite images. We were pretty unsure if we would succeed in seeing the eclipse, because it was pretty cloudy, and especially the low clouds tend to be quite unpredictable. In the end we chose to drive to Middelkerke (near Oostende) in Belgium because of a clear spot approaching from the North Sea.

We arrived at the Belgian coast just in time before sunrise. There we witnessed the eclipse from the top of a dune. About 25 minutes after sunrise the sun appeared from behind the lower clouds, just when the eclipse was at its maximum. It was magical!

First we saw the right ‘horn’ and then the left one appeared. From then on we watched the rest of the eclipse and took many pictures. [no pics from Casper ??]

Later we heard that despite the clouds, many people in The Netherlands were able to see the eclipse. There was a long stretch with a clear zone in the clouds- near the border of Germany.

If they had a clear horizon, people could look underneath the clouds and were just able to see the sunrise. I could even have seen it at home from my apartment on the 13th floor! But the trip was fun. It’s always nice to hunt for the right place to be at these events.

Here are some pictures I took from Middelkerke. They were shot with a Canon 400D in combination with a Meade ETS-70 telescope and a Tamron 20-200mm lens.

Thanks – Yes the hunt is half the fun. ken

………………

Story and Photos sent me by Igal Pat-El, Director, Givatayim Observatory, Tel Aviv, Israel

We took some images of the Jan. 4 Solar Eclipse from the Givatayim Observatory, just near Tel-Aviv, Israel. We were pleased to have Prof. Jay Passachoff as a guest during the eclipse. We had a live broadcast in plan but we had to cancel it due to heavy rain from the first contact, therefore we closed the dome’s shutter and went to the balcony trying to take some quick photos of the eclipse.

Collage assembled by Ken Kremer

We had the portable PST Coronado CaK telescope with a Ca filter On a Alt-Az mount (we could not do any alignment due to the rain). We took about 5 images against all odds in this very dim filter, using the Orion SS II Planetary imager, all of them through the haze and clouds.

Thanks, Igal. Another good lesson learned. Take a chance. You never know what you’ll get till you try !

I’ve combined Igal’s photos into a collage for an enhanced view. ken

See more photos and a video in comments section below

SDO Provides Constant, Unprecedented Views of Sun’s Inner Corona

[/caption]

Usually the only time we can see the innermost part of the Sun’s corona is when there is a total eclipse. But now, with the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) instrument on NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory and a new image processing program, scientists are getting unprecedented views of the innermost corona 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

“The AIA solar images, with better-than-HD quality views, show magnetic structures and dynamics that we’ve never seen before on the Sun,” said astronomer Steven Cranmer from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). “This is a whole new area of study that’s just beginning.”

The Sun’s outer layer, or corona is composed of light, gaseous matter, and has two parts. The outer corona is white, with streamers extending out millions of miles from the edge of the sun. The inner corona, lying next to the red chromosphere, is a band of pale yellow.

This outer layer of the Sun’s atmosphere is, paradoxically, hotter than the Sun’s surface, but so tenuous that its light is overwhelmed by the much brighter solar disk. The corona becomes visible only when the Sun is blocked, which happens for just a few minutes during an eclipse.

Now, with AIA, “we can follow the corona all the way down to the Sun’s surface,” said Leon Golub of the CfA.

Previously, solar astronomers could observe the corona by physically blocking the solar disk with a coronagraph, much like holding your hand in front of your face while driving into the setting Sun. However, a coronagraph also blocks the area immediately surrounding the Sun, leaving only the outer corona visible.

The AIA instrument on SDO allows astronomers to study the corona all the way down to the Sun’s surface.

Cranmer and CfA colleague Alec Engell developed a computer program for processing the AIA images above the Sun’s edge. These processed images imitate the blocking-out of the Sun that occurs during a total solar eclipse, revealing the highly dynamic nature of the inner corona. They will be used to study the initial eruption phase of coronal mass ejections (CMEs) as they leave the Sun and to test theories of solar wind acceleration based on magnetic reconnection.

The resulting images highlight the ever-changing connections between gas captured by the Sun’s magnetic field and gas escaping into interplanetary space.

This time-lapse movie shows two days of solar activity observed by the AIA instrument. Both the solar surface and dynamic inner corona are clearly visible in X-rays. Hot solar plasma streams outward in vast loops larger than Earth before plunging back onto the Sun’s surface. Some of the loops expand and stretch bigger and bigger until they break, belching plasma outward.

SDO launched in February 2010.

This video provides more information about the AIA instrument:

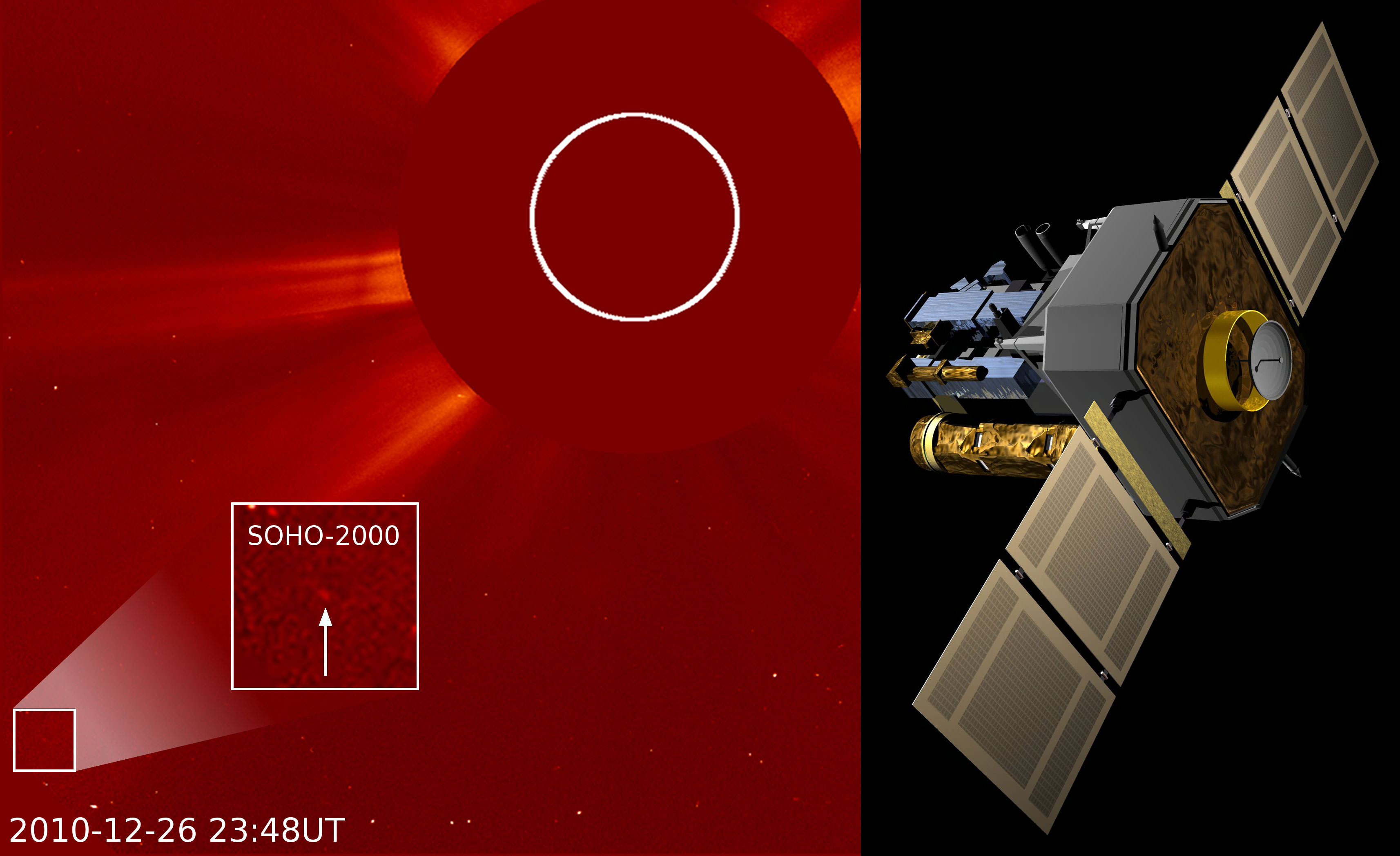

SOHO Finds Its 2000th Comet

[/caption]

As people on Earth celebrate the holidays and prepare to ring in the New Year, an ESA/NASA spacecraft has quietly reached its own milestone: on December 26, the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) discovered its 2000th comet.

Drawing on help from citizen scientists around the world, SOHO has become the single greatest comet finder of all time. This is all the more impressive since SOHO was not specifically designed to find comets, but to monitor the sun.

“Since it launched on December 2, 1995 to observe the sun, SOHO has more than doubled the number of comets for which orbits have been determined over the last three hundred years,” says Joe Gurman, the U.S. project scientist for SOHO at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

Of course, it is not SOHO itself that discovers the comets — that is the province of the dozens of amateur astronomer volunteers who daily pore over the fuzzy lights dancing across the pictures produced by SOHO’s LASCO (or Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph) cameras. Over 70 people representing 18 different countries have helped spot comets over the last 15 years by searching through the publicly available SOHO images online.

The 1999th and 2000th comet were both discovered on December 26 by Michal Kusiak, an astronomy student at Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. Kusiak found his first SOHO comet in November 2007 and has since found more than 100.

“There are a lot of people who do it,” says Karl Battams who has been in charge of running the SOHO comet-sighting website since 2003 for the Naval Research Lab in Washington, where he also does computer processing for LASCO. “They do it for free, they’re extremely thorough, and if it wasn’t for these people, most of this stuff would never see the light of day.”

Battams receives reports from people who think that one of the spots in SOHO’s LASCO images looks to be the correct size and brightness and headed for the sun – characteristics typical of the comets SOHO finds. He confirms the finding, gives each comet an unofficial number, and then sends the information off to the Minor Planet Center in Cambridge, Mass, which categorizes small astronomical bodies and their orbits.

It took SOHO ten years to spot its first thousand comets, but only five more to find the next thousand. That’s due partly to increased participation from comet hunters and work done to optimize the images for comet-sighting, but also due to an unexplained systematic increase in the number of comets around the sun. Indeed, December alone has seen an unprecedented 37 new comets spotted so far, a number high enough to qualify as a “comet storm.”

LASCO was not designed primarily to spot comets. The LASCO camera blocks out the brightest part of the sun in order to better watch emissions in the sun’s much fainter outer atmosphere, or corona. LASCO’s comet finding skills are a natural side effect — with the sun blocked, it’s also much easier to see dimmer objects such as comets.

“But there is definitely a lot of science that comes with these comets,” says Battams. “First, now we know there are far more comets in the inner solar system than we were previously aware of, and that can tell us a lot about where such things come from and how they’re formed originally and break up. We can tell that a lot of these comets all have a common origin.” Indeed, says Battams, a full 85% of the comets discovered with LASCO are thought to come from a single group known as the Kreutz family, believed to be the remnants of a single large comet that broke up several hundred years ago.

The Kreutz family comets are “sungrazers” – bodies whose orbits approach so near the Sun that most are vaporized within hours of discovery – but many of the other LASCO comets boomerang around the sun and return periodically. One frequent visitor is comet 96P Machholz. Orbiting the sun approximately every six years, this comet has now been seen by SOHO three times.

SOHO is a cooperative project between the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA. The spacecraft was built in Europe for ESA and equipped with instruments by teams of scientists in Europe and the USA.

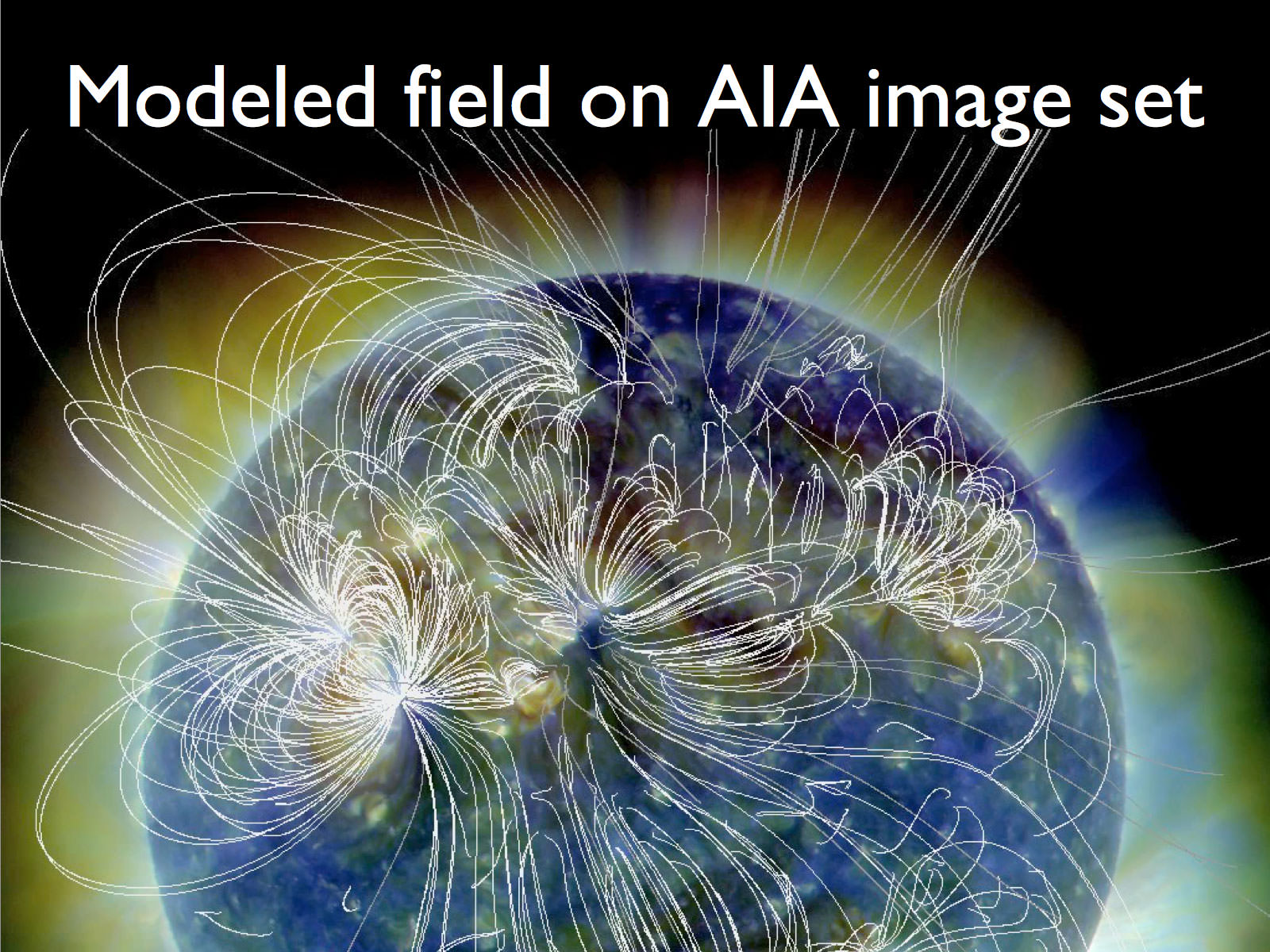

Near-Synchronous Explosions Connect Across the Vast Distances on the Sun

For several decades, scientists studying the sun have observed solar flares that appear to occur almost simultaneously but originated in completely different areas on the Sun. Solar physicists called them “sympathetic” flares, but it was thought these near-synchronous explosions in the solar atmosphere were too far apart – sometimes millions of kilometers distant – to be related. But now, with the continuous high-resolution and multi-wavelength observations with the Solar Dynamics Observatory, combined with views from the twin STEREO spacecraft, the scientists are seeing how these sympathetic eruptions — sometimes on opposite sides of the sun — can connect through looping lines of the Sun’s magnetic field.

“The high-quality simultaneous data we received from SDO and the STEREO spacecraft, and our subsequent analysis, enable us to present unambiguous evidence that solar regions up to 160 degrees away are involved in defining the large-scale coronal field topology for flares and CMEs,” said Dr. Carolus Schrijver, who co-presented his team’s findings at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

“From the very first observations with SDO we saw small events seemed to impact large regions of the sun,” said Alan Title of the Solar and Astrophysics Lab at Lockheed Martin, and co-author of the paper, speaking at a press briefing, “but because we are scientists and are sometimes not very clever, we have to sometimes be beaten over the head, and went searching for some kind of causality. It has been in last couple of months where we worked out this picture together.”

The hammer on the head was a series of solar events that took place on August 1, 2010, where nearly the entire Earth-facing side of the Sun erupted in a tumult of activity, with a large solar flare, a solar tsunami, multiple filaments of magnetism lifting off the solar surface, radio bursts, and half a dozen coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

SDO, which launched in February of this year, along with the two Solar Terrestrial Relations

Observatory (STEREO) spacecraft — were ideally positioned to capture both the action on the Earth-facing side of the Sun, and most activity around the backside, leaving a wedge of only 30 degrees of the solar surface unobserved.

SDO’s Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) continuously observes the full solar corona and can trace perturbations over long distances, even if short-lived. The STEREO spacecraft were able to provide perspectives on activity on most of the “back side” of the Sun, and perhaps most importantly, SDO’s Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI) provided global magnetic field connections.

[/caption]

As seen in the image above, the looping magnetic field lines connected the various events on August 1. Subsequent observations have revealed similar events.

“The magnetic field lines connect to other flares and other major events, with the eruptions and flares frequently coupled across large distances,” said Schrijver. “Previously, we had been looking for the cause of explosions just in the regions from where the explosions were coming from. That might be a good way to do it, but these observations show another aspect. If we wish to know why the flare goes off, we need to know not just properties of region but also a large fraction of the solar surface, in fact sometimes not even part we can see. So maybe reason we had difficulty figuring this out was that we were not seeing everything. We have to expand our view and look at everything.”

Title compared finally figuring out that these near synchronous events are related to how scientists finally figured out continental drift. “Everyone could see how Africa and South America could have once fit together, but no one could imagine the physical processes that could make that happen,” he said, “but all of a sudden someone measured it and figured out sea floor spreading and it made perfect sense.”

In response to a question of whether the magnetic field on the Sun has areas similar to fault lines on the Earth where magnetic lines emerge repeatedly, Schrijver told Universe Today that the magnetic field lines come from the deep within the solar interior, but why it chooses to emerge in certain areas repeatedly is a mystery. “There are successive nests, where they come up one after another, or preferred regions,” he said, but our details on this are fairly weak. Most of time we don’t know where magnetic field lines will emerge from the sun.”

Title said heliophysics research is still in its infancy, but the new resources SDO provides might bring a new era in this area of study.

“We’ve reached a turning point in our ability to forecast space weather,” said Title. “We now have evidence that multiple events can be triggered by other events that occur in regions that cannot be observed from Earth orbit. This gives us a new appreciation of why solar flare and CME predictions have been less than perfect. As we seek to understand the causes of eruptive and explosive events that will improve our ability to forecast space weather, it is clear that we must be able to analyze most of the evolving global solar field, if not all of it.”

Voyager 1 Has Outdistanced the Solar Wind

[/caption]

The venerable Voyager spacecraft are truly going where no one has gone before. Voyager 1 has now reached a distant point at the edge of our solar system where it is no longer detecting the solar wind. At a distance of about 17.3 billion km (10.8 billion miles) from the Sun, Voyager 1 has crossed into an area where the velocity of the hot ionized gas, or plasma, emanating directly outward from the sun has slowed to zero. Scientists suspect the solar wind has been turned sideways by the pressure from the interstellar wind in the region between stars.

“The solar wind has turned the corner,” said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist based at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif. “Voyager 1 is getting close to interstellar space.”

The event is a major milestone in Voyager 1’s passage through the heliosheath, the turbulent outer shell of the sun’s sphere of influence, and the spacecraft’s upcoming departure from our solar system.

Since its launch on Sept. 5, 1977, Voyager 1’s Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument has been used to measure the solar wind’s velocity.

When the speed of the charged particles hitting the outward face of Voyager 1 matched the spacecraft’s speed, researchers knew that the net outward speed of the solar wind was zero. This occurred in June, when Voyager 1 was about 10.6 billion miles from the sun.

However, velocities can fluctuate, so the scientists watched four more monthly readings before they were convinced the solar wind’s outward speed actually had slowed to zero. Analysis of the data shows the velocity of the solar wind has steadily slowed at a rate of about 45,000 mph each year since August 2007, when the solar wind was speeding outward at about 130,000 mph. The outward speed has remained at zero since June.

“When I realized that we were getting solid zeroes, I was amazed,” said Rob Decker, a Voyager Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument co-investigator and senior staff scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. “Here was Voyager, a spacecraft that has been a workhorse for 33 years, showing us something completely new again.”

Scientists believe Voyager 1 has not crossed the heliosheath into interstellar space. Crossing into interstellar space would mean a sudden drop in the density of hot particles and an increase in the density of cold particles. Scientists are putting the data into their models of the heliosphere’s structure and should be able to better estimate when Voyager 1 will reach interstellar space. Researchers currently estimate Voyager 1 will cross that frontier in about four years.

Our sun gives off a stream of charged particles that form a bubble known as the heliosphere around our solar system. The solar wind travels at supersonic speed until it crosses a shockwave called the termination shock. At this point, the solar wind dramatically slows down and heats up in the heliosheath.

A sister spacecraft, Voyager 2, was launched in Aug. 20, 1977 and has reached a position 8.8 billion miles from the sun. Both spacecraft have been traveling along different trajectories and at different speeds. Voyager 1 is traveling faster, at a speed of about 38,000 mph, compared to Voyager 2’s velocity of 35,000 mph. In the next few years, scientists expect Voyager 2 to encounter the same kind of phenomenon as Voyager 1.

The results were presented at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco.

Source: NASA