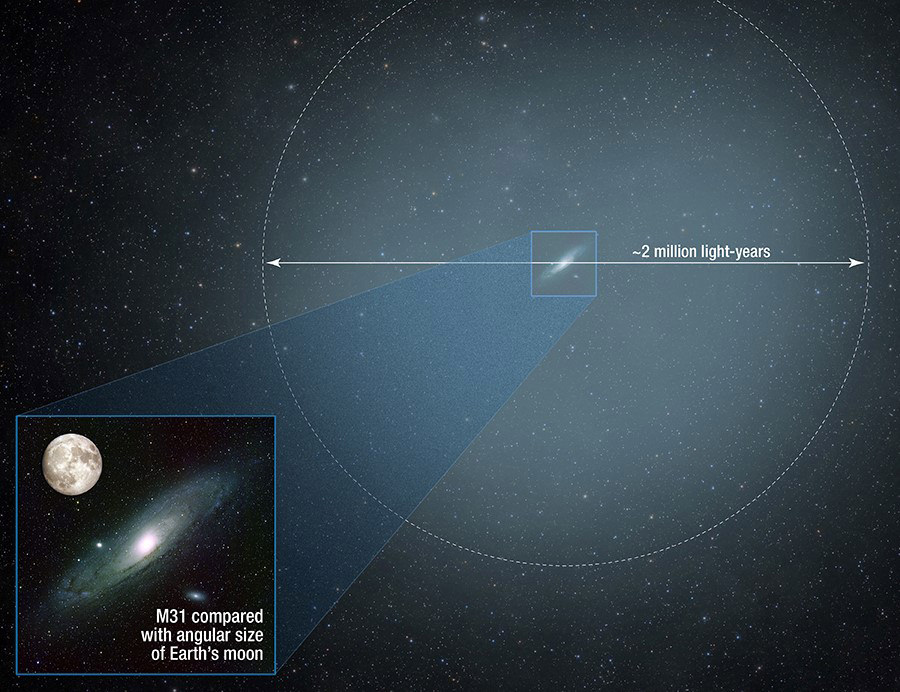

The merger of the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxy won’t happen for another 4 billion years, but the recent discovery of a massive halo of hot gas around Andromeda may mean our galaxies are already touching. University of Notre Dame astrophysicist Nicholas Lehner led a team of scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope to identify an enormous halo of hot, ionized gas at least 2 million light years in diameter surrounding the galaxy.

The Andromeda Galaxy is the largest member of a ragtag collection of some 54 galaxies, including the Milky Way, called the Local Group. With a trillion stars — twice as many as the Milky Way — it shines 25% brighter and can easily be seen with the naked eye from suburban and rural skies.

Think about this for a moment. If the halo extends at least a million light years in our direction, our two galaxies are MUCH closer to touching that previously thought. Granted, we’re only talking halo interactions at first, but the two may be mingling molecules even now if our galaxy is similarly cocooned.

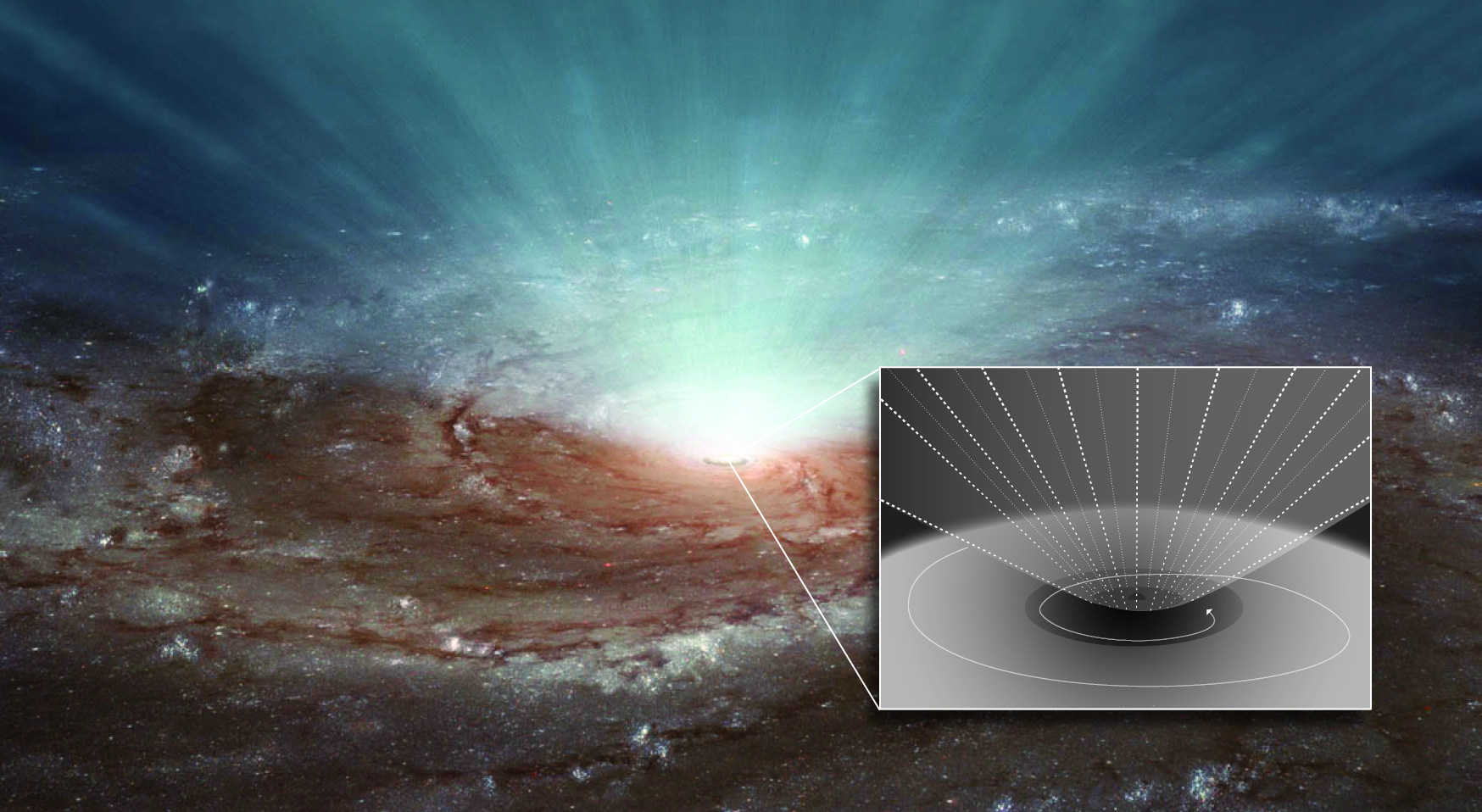

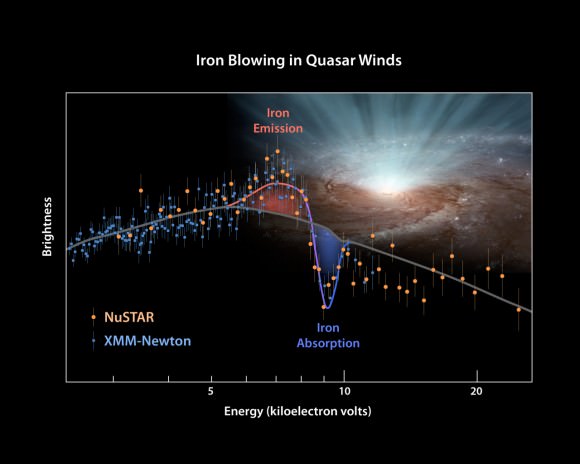

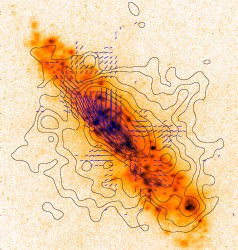

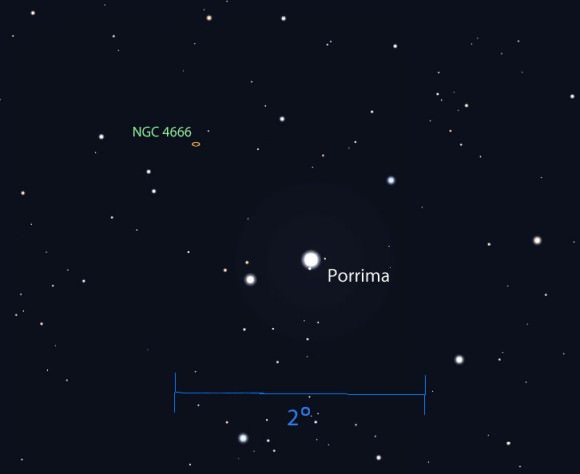

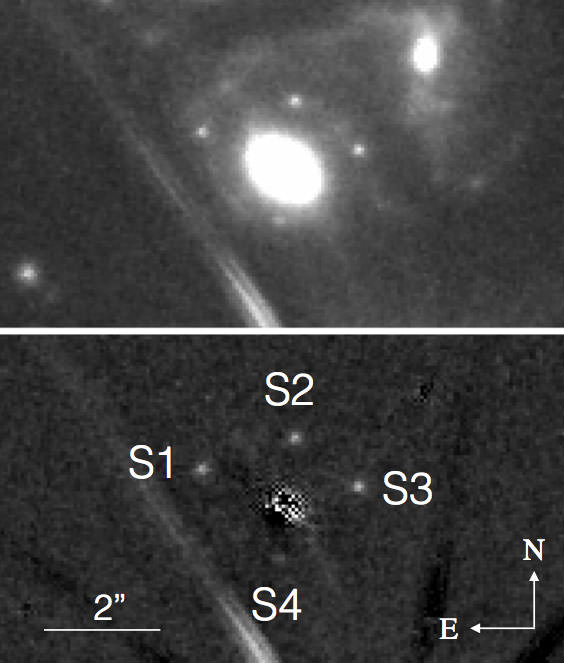

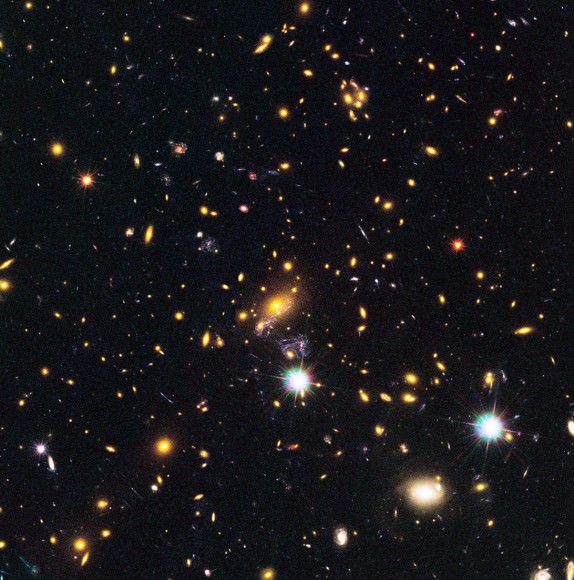

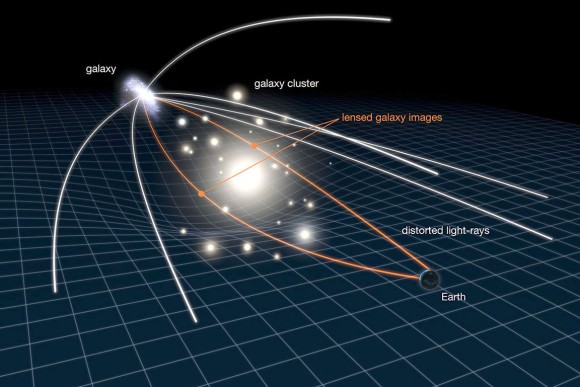

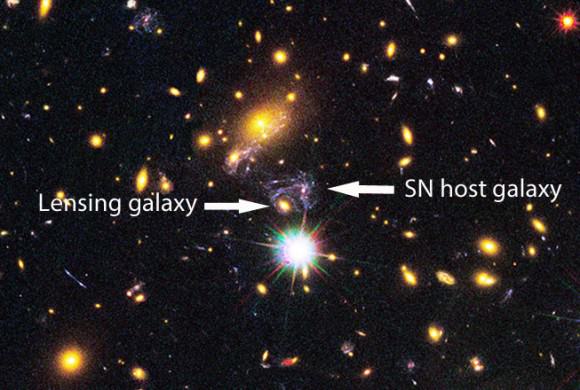

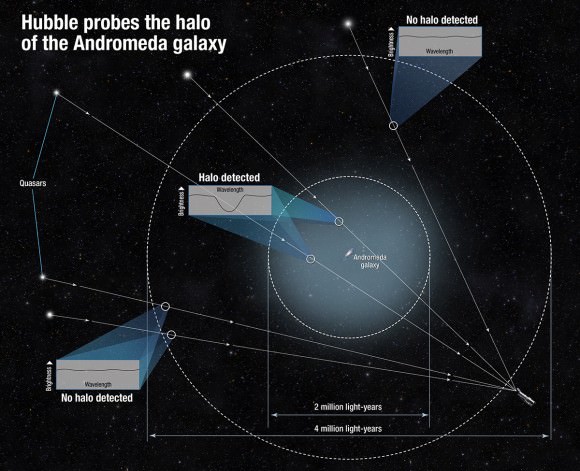

Lehner describes halos as the “gaseous atmospheres of galaxies”. Despite its enormous size, Andromeda’s nimbus is virtually invisible. To find and study the halo, the team sought out quasars, distant star-like objects that radiate tremendous amounts of energy as matter funnels into the supermassive black holes in their cores. The brightest quasar, 3C273 in Virgo, can be seen in a 6-inch telescope! Their brilliant, pinpoint nature make them perfect probes.

“As the light from the quasars travels toward Hubble, the halo’s gas will absorb some of that light and make the quasar appear a little darker in just a very small wavelength range,” said J. Christopher Howk , associate professor of physics at Notre Dame and co-investigator. “By measuring the dip in brightness, we can tell how much halo gas from M31 there is between us and that quasar.”

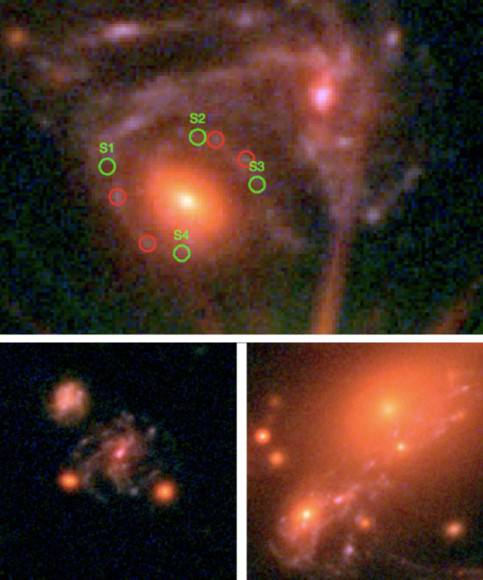

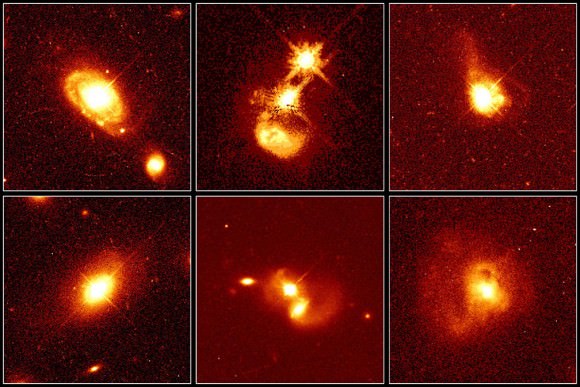

Astronomers have observed halos around 44 other galaxies but never one as massive as Andromeda where so many quasars are available to clearly define its extent. The previous 44 were all extremely distant galaxies, with only a single quasar or data point to determine halo size and structure.

Andromeda’s close and huge with lots of quasars peppering its periphery. The team drew from about five years’ worth of observations of archived Hubble data to find many of the 18 objects needed for a good sample.

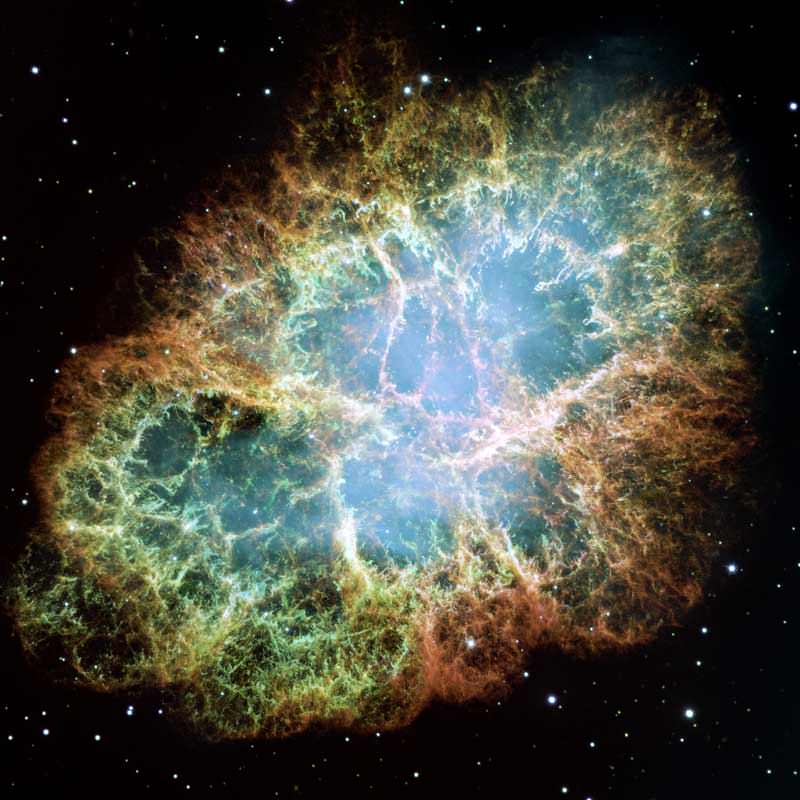

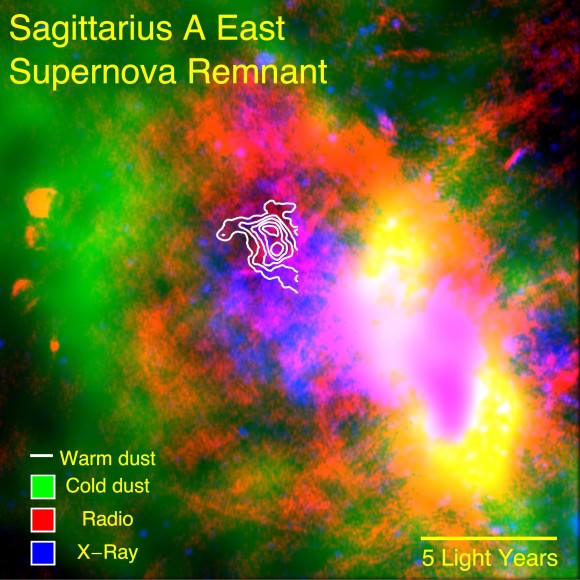

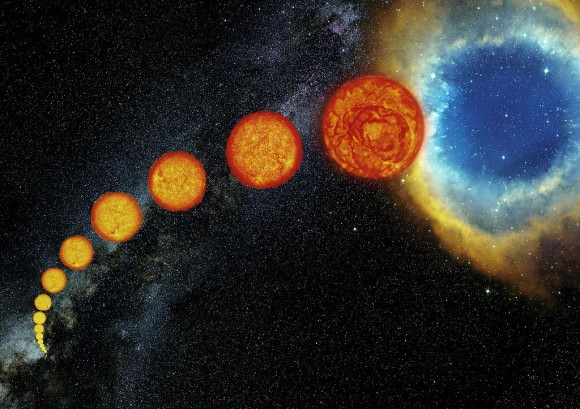

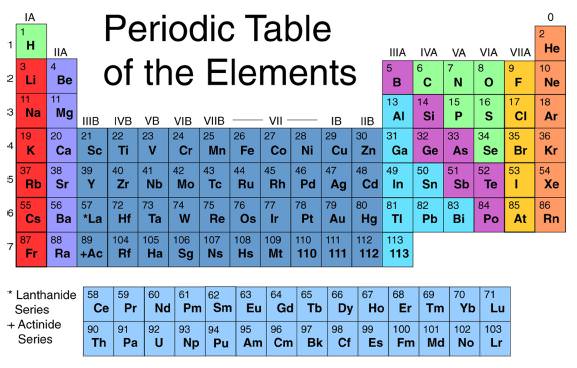

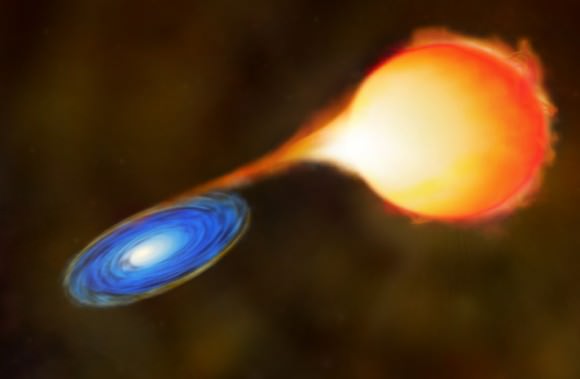

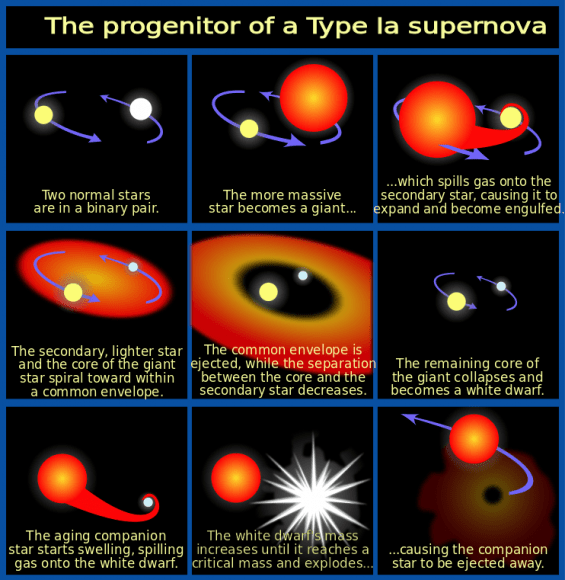

The halo is estimated to contain half the mass of the stars in the Andromeda galaxy itself, in the form of a hot, diffuse gas. Simulations suggest that it formed at the same time as the rest of the galaxy. Although mostly composed of ionized hydrogen — naked protons and electrons — Andromeda’s aura is also rich in heavier elements, probably supplied by supernovae. They erupt within the visible galaxy and violently blow good stuff like iron, silicon, oxygen and other familiar elements far into space. Over Andromeda’s lifetime, nearly half of all the heavy elements made by its stars have been expelled far beyond the galaxy’s 200,000-light-year-diameter stellar disk.

You might wonder if galactic halos might account for some or much of the still-mysterious dark matter. Probably not. While dark matter still makes up the bulk of the solid material in the universe, astronomers have been trying to account for the lack of visible matter in galaxies as well. Halos now seem a likely contributor.

The next clear night you look up to spy Andromeda, know this: It’s closer than you think!

For more on the topic, here are links to Lehner’s paper in the Astrophysical Journal and the Hubble release.