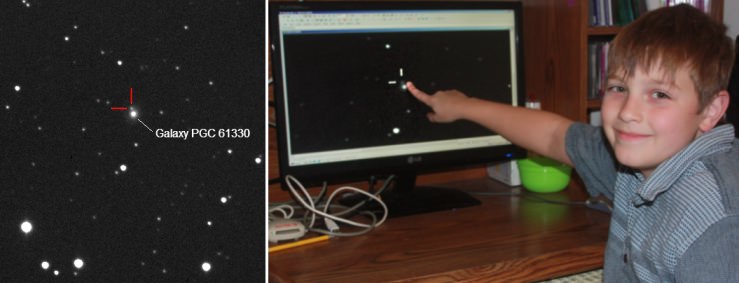

In a rare example of cloudy weather helping astronomy rather than hurting it, the team that found M82’s new supernova swung a telescope in that direction only because their planned targets for the night were obscured, a release stated.

The exploding star in the “Cigar Galaxy” was found at 7:20 p.m. UTC (2:20 p.m. EST) during a class taught by Steve Fossey at the University of London Observatory. Students Ben Cooke, Tom Wright, Matthew Wilde and Guy Pollack all participated in the discovery.

“The weather was closing in, with increasing cloud,” recalled Fossey in a press release, “so instead of the planned practical astronomy class, I gave the students an introductory demonstration of how to use the CCD camera on one of the observatory’s automated 0.35–metre [1.14-foot] telescopes.”

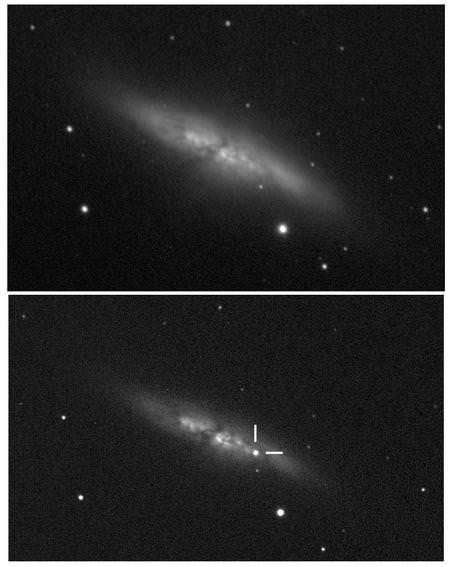

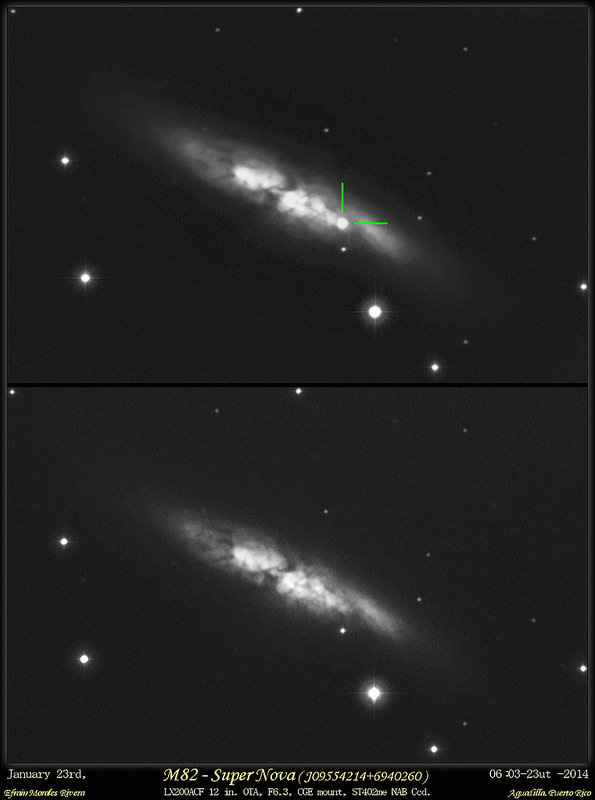

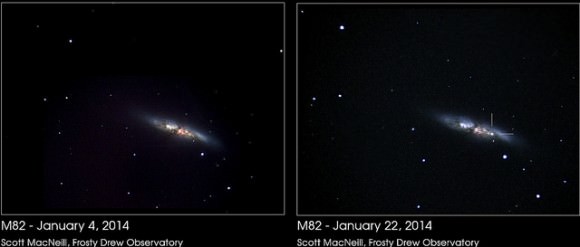

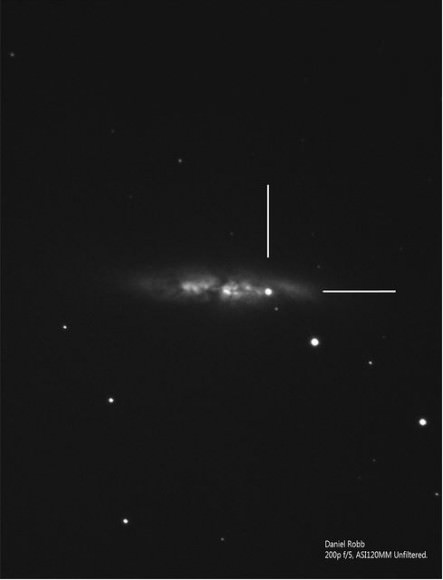

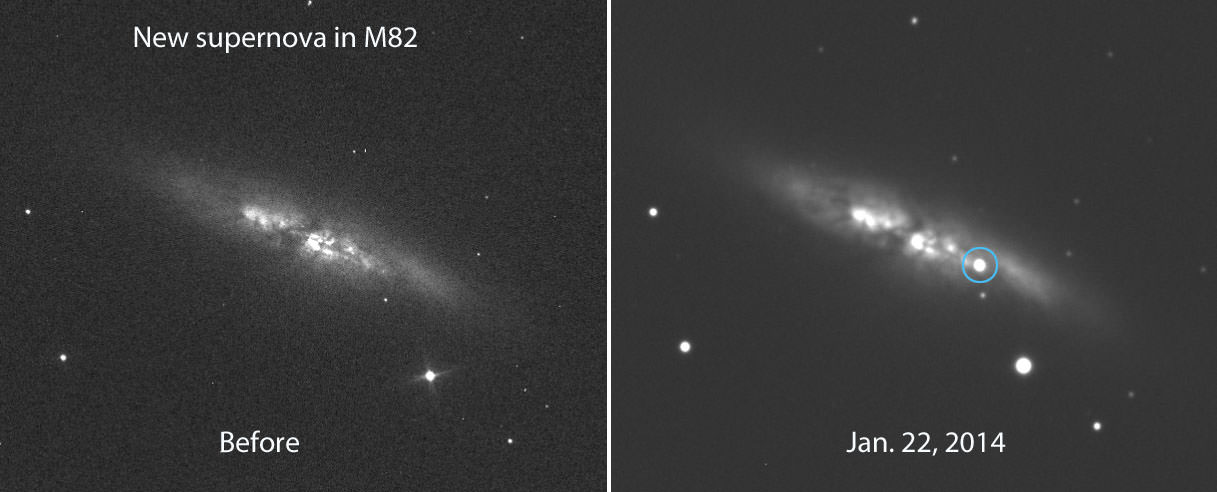

The students asked for M82, at which point Fossey saw a star that he couldn’t recall from examining the galaxy previously. A search of other images online revealed that something strange was happening, but clouds were obscuring everything quickly. The team focused on taking one- and two-minute exposures with different filters, and also using a second telescope to make sure there wasn’t something wrong with the first.

The team checked for any reports of a supernova, and finding none, Fossey sent a message to the International Astronomical Union’s Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (which catalogs supernovae) and a United States team that does regular searches for exploding stars. Among his concerns was that it could be an asteroid lying in the way of the galaxy, but further spectroscopic measurements confirmed the “fluke” find, the release added.

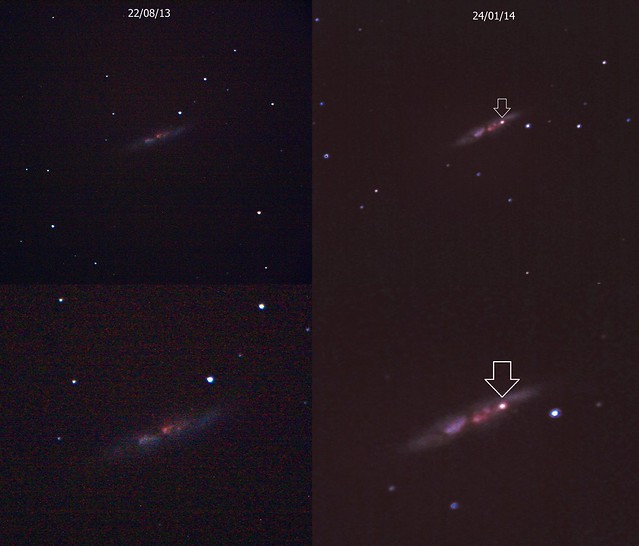

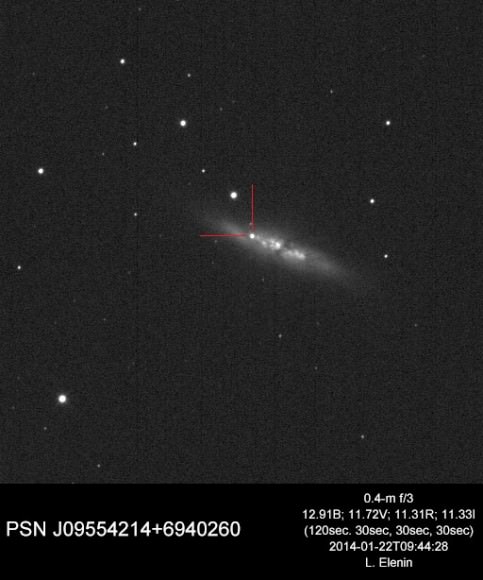

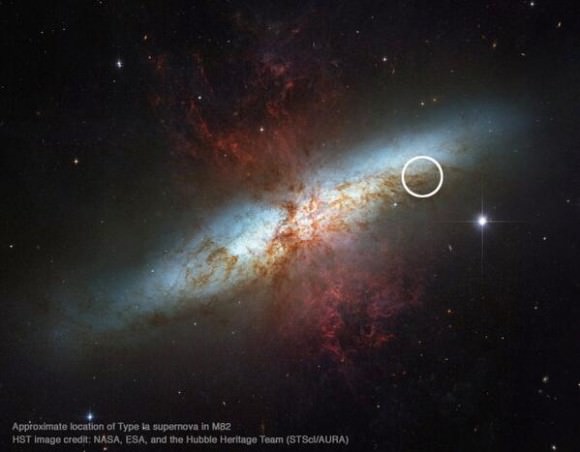

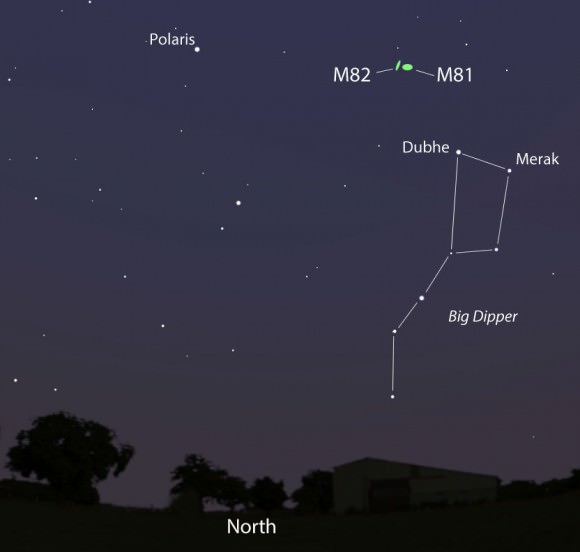

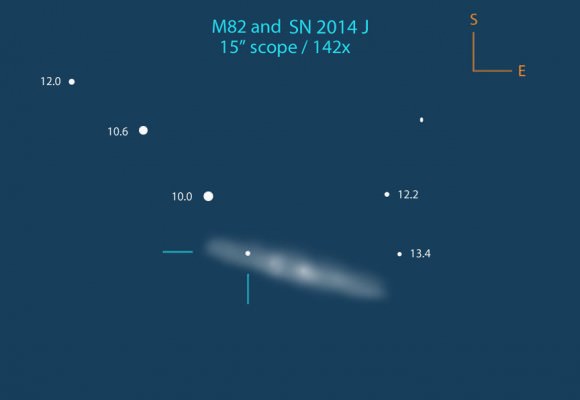

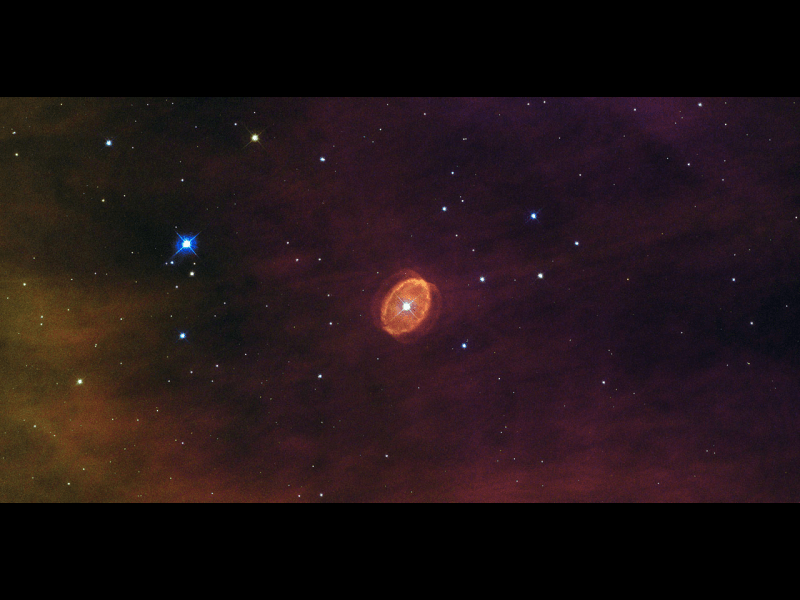

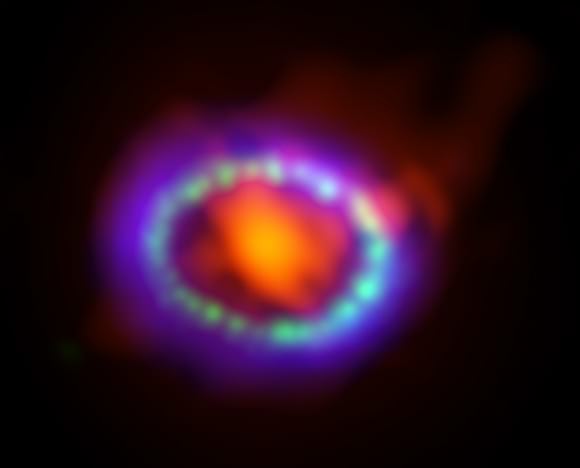

The great thing about SN 2014J is it’s visible even in small telescopes. It’s also fairly close, by astronomical standards, at about 12 million light-years away. (The closest found since the invention of the telescope was Supernova 1987A, which exploded in February 1987 and was 168,000 light-years away.) Astrophotographers have already snapped many images of the exploding star.

“One minute we’re eating pizza, then five minutes later we’ve helped to discover a supernova,” stated Wright. “I couldn’t believe it. It reminds me why I got interested in astronomy in the first place.”

Source: University College London