Some of the most violent events in our Universe were the topic of discussion this morning at the 222nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Indianapolis, Indiana as researchers revealed recent observations of light echoes seen as the result of stellar explosions.

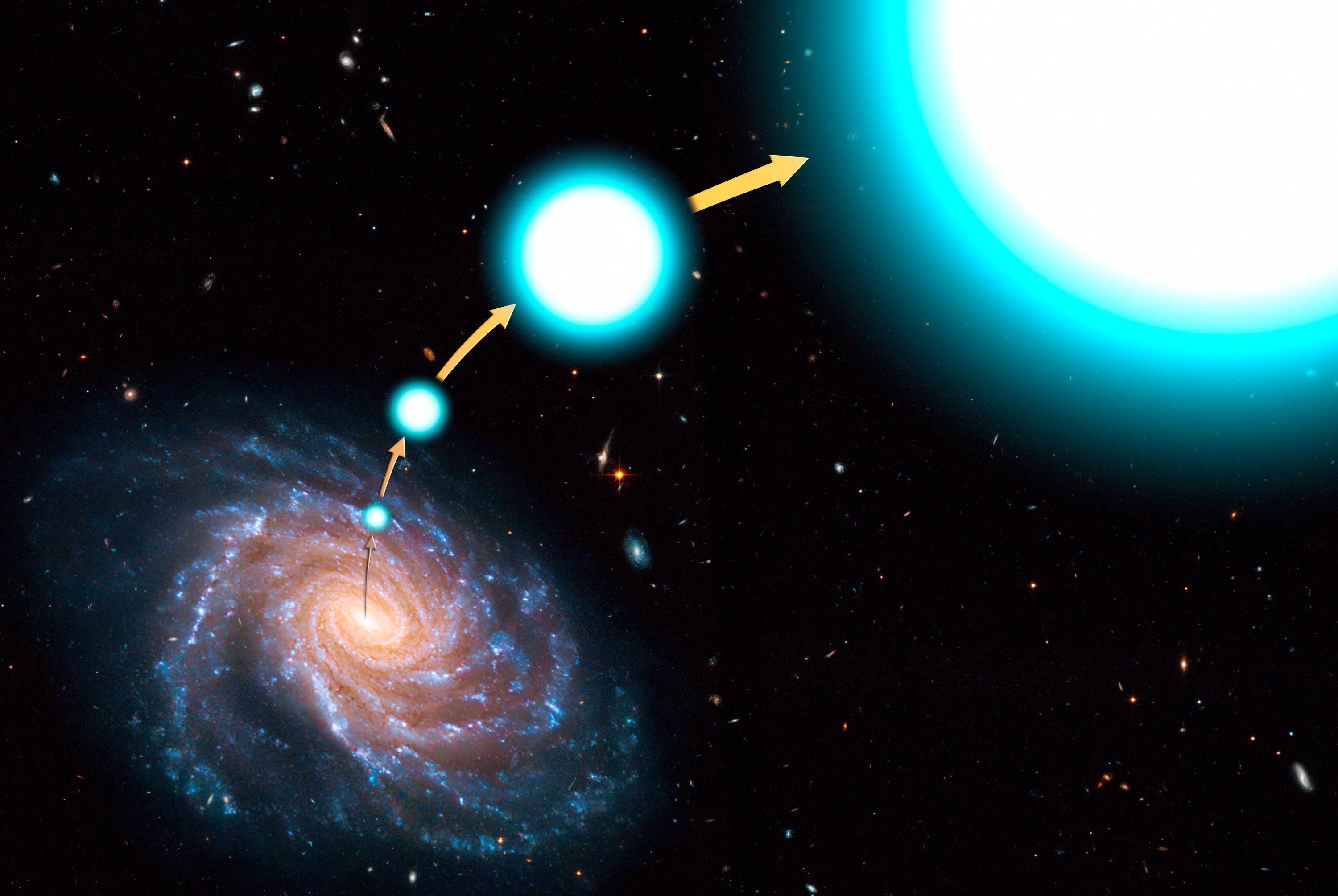

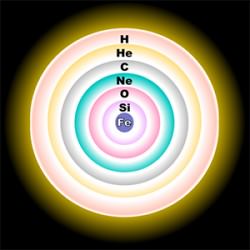

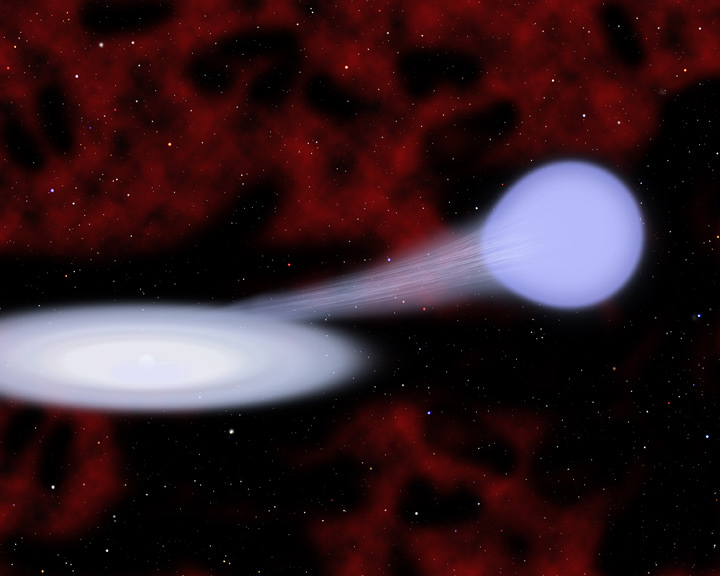

A light echo occurs when we see dust and ejected material illuminated by a brilliant nova. A similar phenomenon results in what is termed as a reflection nebula. A star is said to go nova when a white dwarf star siphons off material from a companion star. This accumulated hydrogen builds up under terrific pressure, sparking a brief outburst of nuclear fusion.

A very special and rare case is a class of cataclysmic variables known as recurrent novae. Less than dozen of these types of stars are known of in our galaxy, and the most famous and bizarre case is that of T Pyxidis.

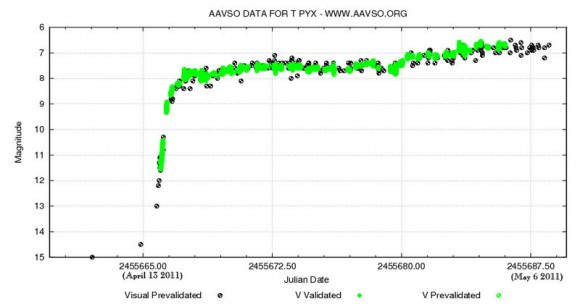

Located in the southern constellation of Pyxis, T Pyxidis generally hovers around +15th magnitude, a faint target even in a large backyard telescope. It has been prone, however, to great outbursts approaching naked eye brightness roughly every 20 years to magnitude +6.4. That’s a change in brightness almost 4,000-fold.

But the mystery has only deepened surrounding this star. Eight outbursts were monitored by astronomers from 1890 to 1966, and then… nothing. For decades, T Pyxidis was silent. Speculation shifted from when T Pyxidis would pop to why this star was suddenly undergoing a lengthy phase of silence.

Could models for recurrent novae be in need of an overhaul?

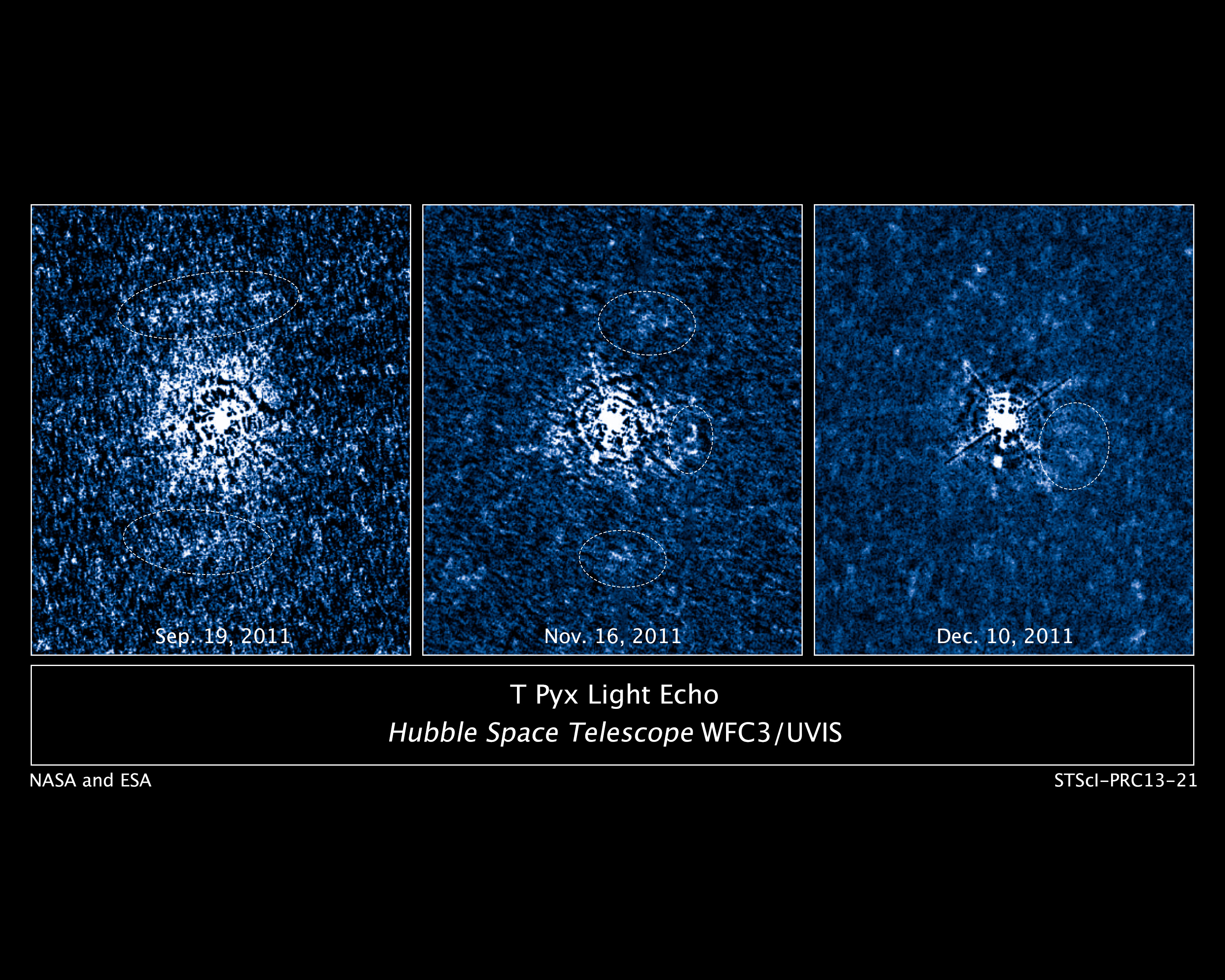

T Pyxidis finally answered astronomers’ questions in 2011, undergoing its first outburst in 45 years. And this time, they had the Hubble Space Telescope on hand to witness the event.

In fact, Hubble had just been refurbished during the final visit of the space shuttle Atlantis to the orbiting observatory in 2009 on STS-125 with the installation of its Wide Field Camera 3, which was used to monitor the outburst of T Pyxidis.

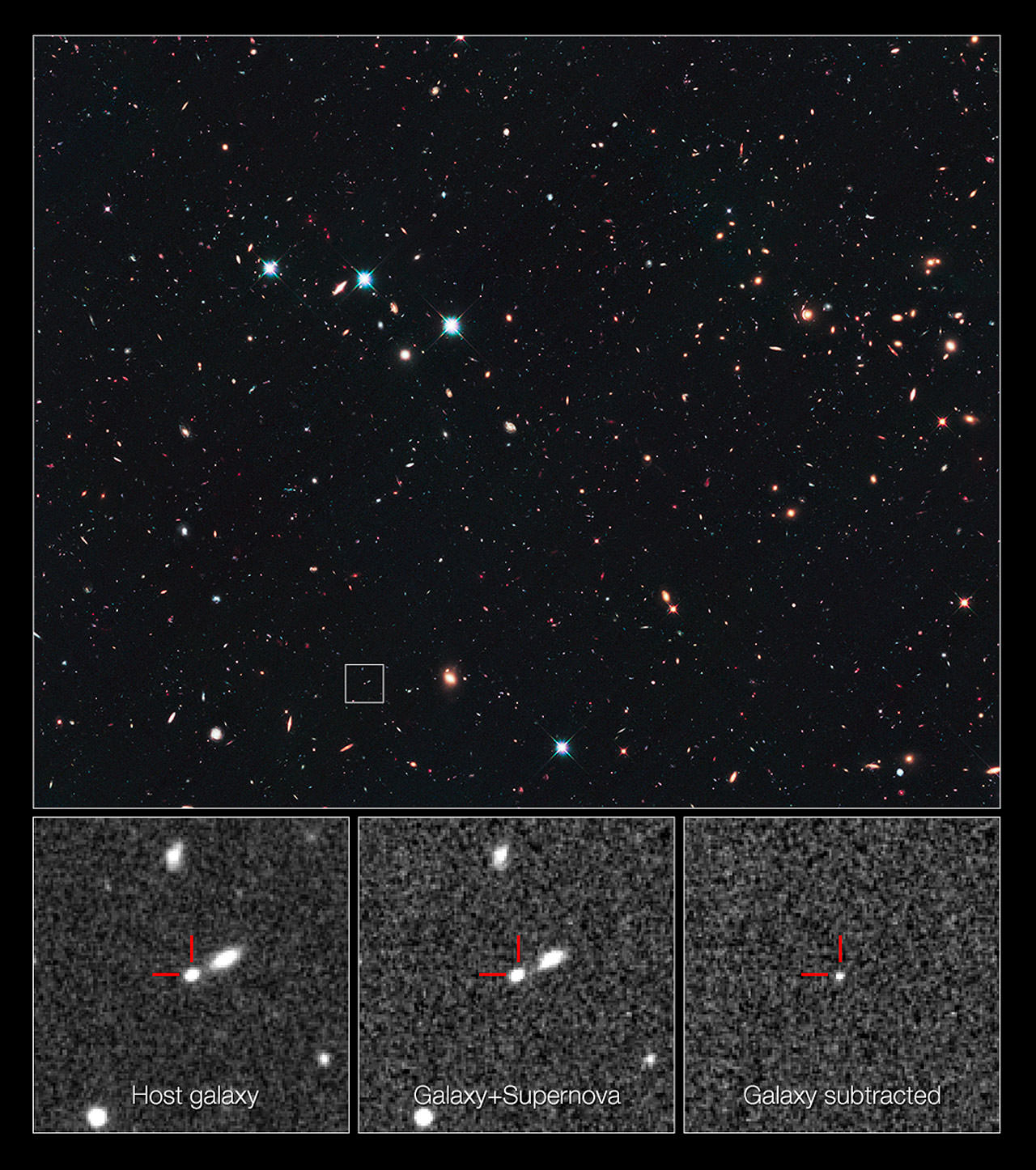

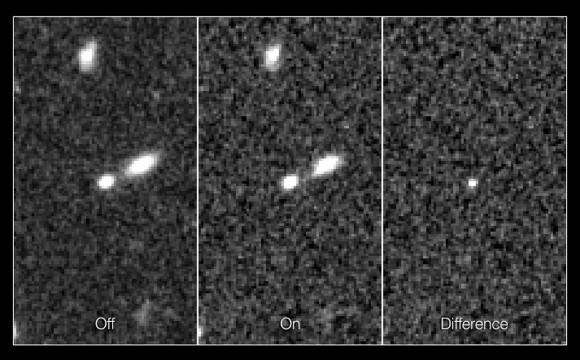

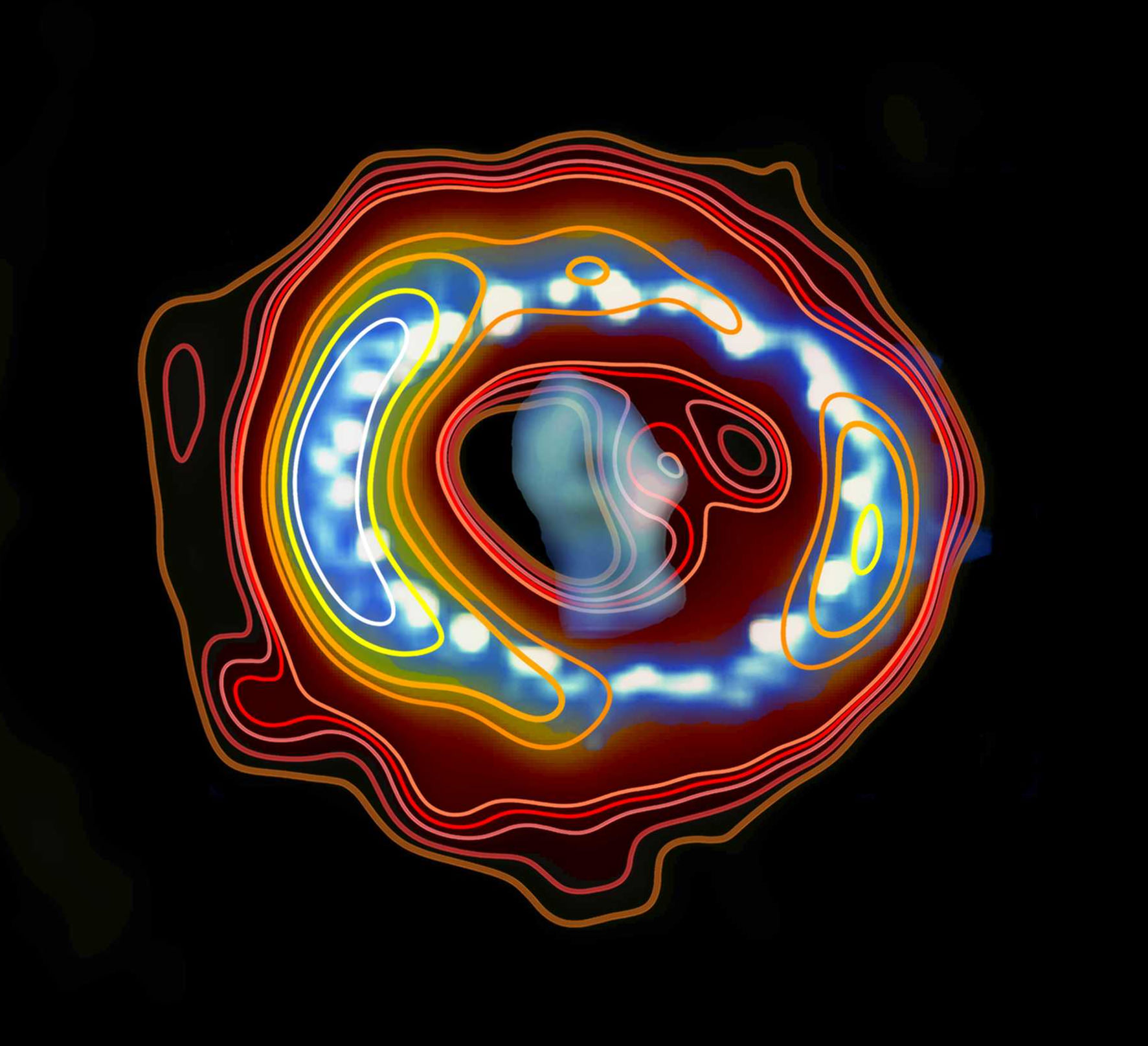

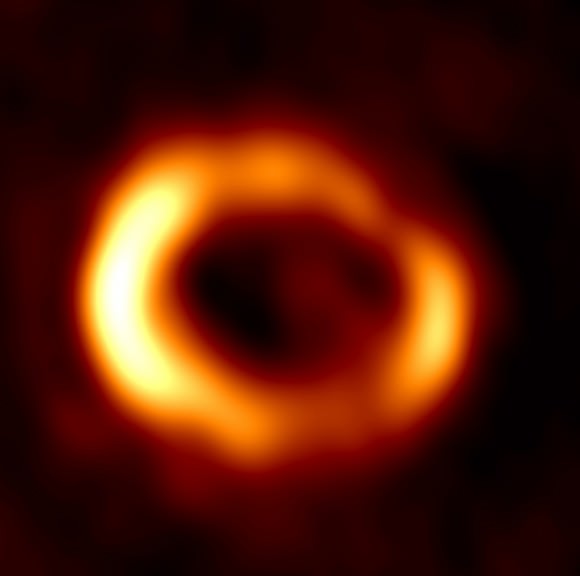

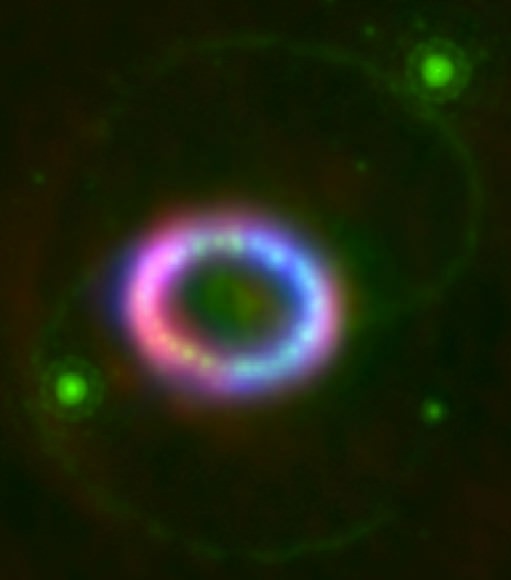

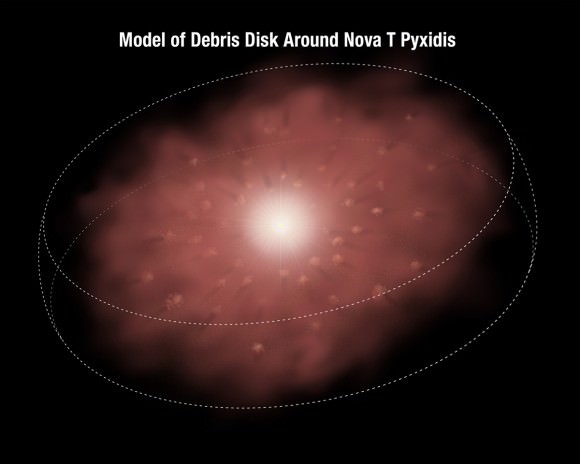

The Hubble observation of the light echo provided some surprises for astronomers as well.

“We fully expected this to be a spherical shell,” Said Columbia University’s Arlin Crotts, referring to the ejecta in the vicinity of the star. “This observation shows it is a disk, and it is populated with fast-moving ejecta from previous outbursts.”

Indeed, this discovery raises some exciting possibilities, such as providing researchers with the ability to map the anatomy of previous outbursts from the star as the light echo evolves and illuminates the 3-D interior of the disk like a Chinese lantern. The disk is inclined about 30 degrees to our line of sight, and researchers suggest that the companion star may play a role in the molding of its structure from a sphere into a disk. The disk of material surrounding T Pyxidis is huge, about 1 light year across. This results in an apparent ring diameter of 6 arc seconds (about 1/8th the apparent size of Jupiter at opposition) as seen from our Earthly vantage point.

Paradoxically, light echoes can appear to move at superluminal speeds. This illusion is a result of the geometry of the path that the light takes to reach the observer, crossing similar distances but arriving at different times.

And speaking of distance, measurement of the light echoes has given astronomers another surprise. T Pyxidis is located about 15,500 light years distant, at the higher 10% end of the previous 6,500-16,000 light year estimated range. This means that T Pyxidis is an intrinsically bright object, and its outbursts are even more energetic than thought.

Light echoes have been studied surrounding other novae, but this has been the first time that scientists have been able to map them extensively in 3 dimensions.

“We’ve all seen how light from fireworks shells during the grand finale will light up the smoke and soot from the shells earlier in the show,” said team member Stephen Lawrence of Hofstra University. “In an analogous way, we’re using light from T Pyx’s latest outburst and its propagation at the speed of light to dissect its fireworks displays from decades past.”

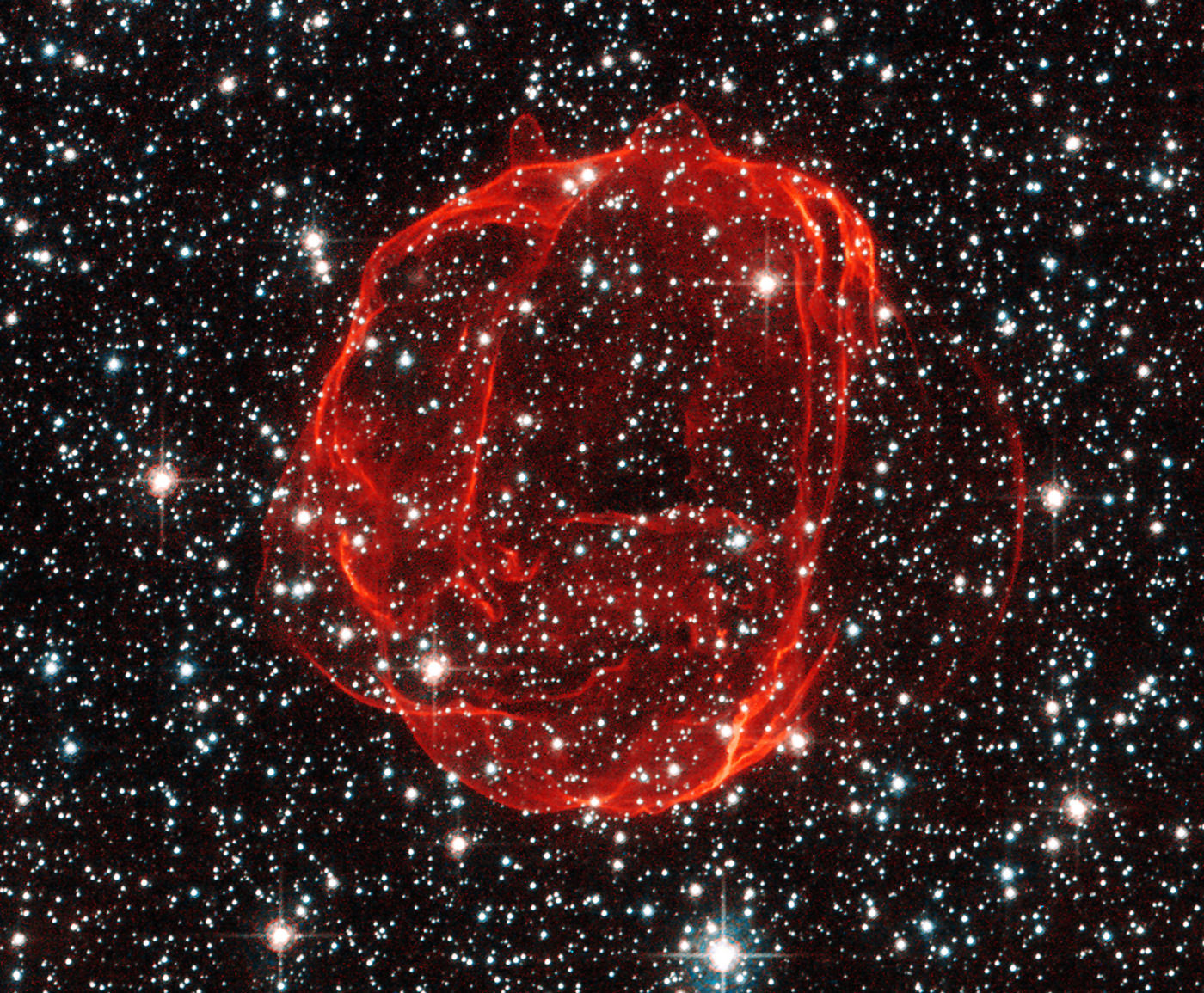

Researchers also told Universe Today of the role which amateur astronomers have played in monitoring these outbursts. Only so much “scope time” exists, very little of which can be allocated exclusively to the study of light echoes. Amateurs and members of the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) are often the first to alert the pros that an outburst is underway. A famous example of this occurred in 2010, when Florida-based backyard observer Barbara Harris was the first to spot an outburst from recurrent novae U Scorpii.

And although T Pyxidis may now be dormant for the next few decades, there are several other recurrent novae worth continued scrutiny:

| Name | Max brightness | Right Ascension | Declination | Last Eruption | Period(years) |

| U Scorpii | +7.5 | 16H 22’ 31” | -17° 52’ 43” | 2010 | 10 |

| T Pyxidis | +6.4 | 9H 04’ 42” | -32° 22’ 48” | 2011 | 20 |

| RS Ophiuchi | +4.8 | 17H 50’ 13” | -6° 42’ 28” | 2006 | 10-20 |

| T Coronae Borealis | +2.5 | 15H 59’ 30” | 25° 55’ 13” | 1946 | 80? |

| WZ Sagittae | +7.0 | 20H 07’ 37” | +17° 42’ 15” | 2001 | 30 |

Clearly, recurrent novae have a tale to tell us of the role they play in the cosmos. Congrats to Lawrence and team on the discovery… keep an eye out from future fireworks from this rare class of star!

Read the original NASA press release and more on T Pyxidis here.