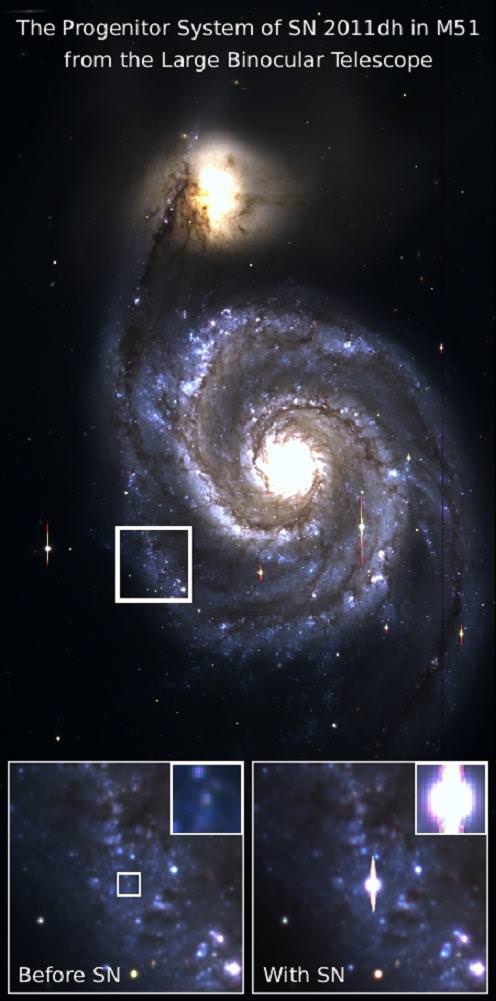

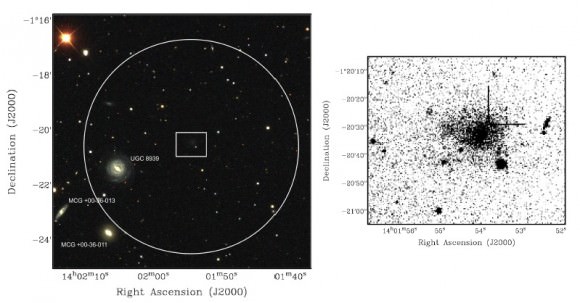

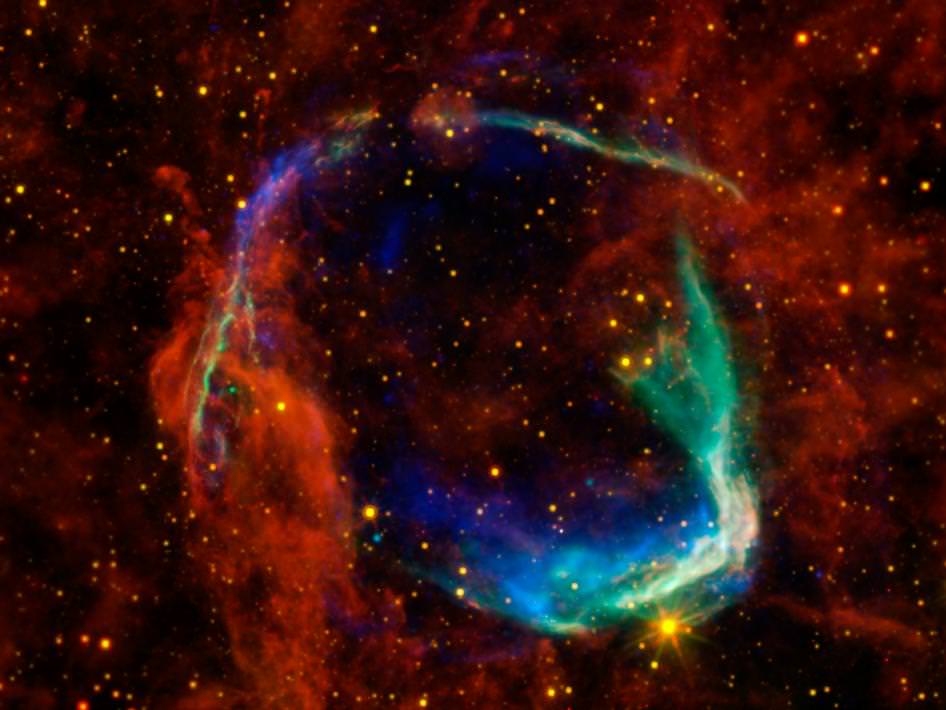

[/caption] This past year has given both backyard and professional astronomers a rare treat – a very visible supernova event. Hosted in the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51), these stellar death throes may have been clued to us by a rather ordinary binary star system. In a recent study done by researchers at Ohio State University, a galaxy survey may have captured evidence of a “stellar signal” just before it went supernova!

Employing the Large Binocular Telescope located in Arizona, the OSU team was undertaking a survey of 25 galaxies for stars that changed their magnitude in usual ways. Their goal was to find a star just before it ended its life – a three-year undertaking. As luck would have it, a binary star system located in M51 produced just the results they were looking for. One star dropped amplitude just a short period of time before the other exploded. While the probability factor of them getting the exact star might be slim, chances are still good they caught its brighter partner. Despite that, principal investigator Christopher Kochanek, professor of astronomy at Ohio State and the Ohio Eminent Scholar in Observational Cosmology, remains optimistic as their results prove a theory.

“Our underlying goal is to look for any kind of signature behavior that will enable us to identify stars before they explode,” he said. “It’s a speculative goal at this point, but at least now we know that it’s possible.”

“Maybe stars give off a clear signal of impending doom, maybe they don’t,” said study co-author Krzystof Stanek, professor of astronomy at Ohio State, “But we’ll learn something new about dying stars no matter the outcome.”

Postdoctoral researcher Dorota Szczygiel, the leader of the supernova study tells us why the galaxy survey remains paramount.

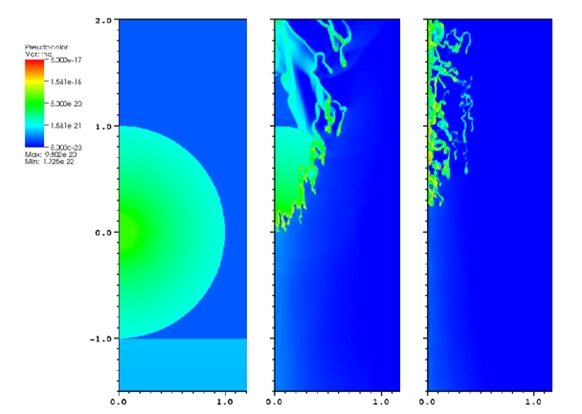

“The odds are extremely low that we would just happen to be observing a star for several years before it went supernova. We would have to be extremely lucky,” she said. “With this galaxy survey, we’re making our own luck. We’re studying all the variable stars in 25 galaxies, so that when one of them happens go supernova, we’ve already compiled data on it.”

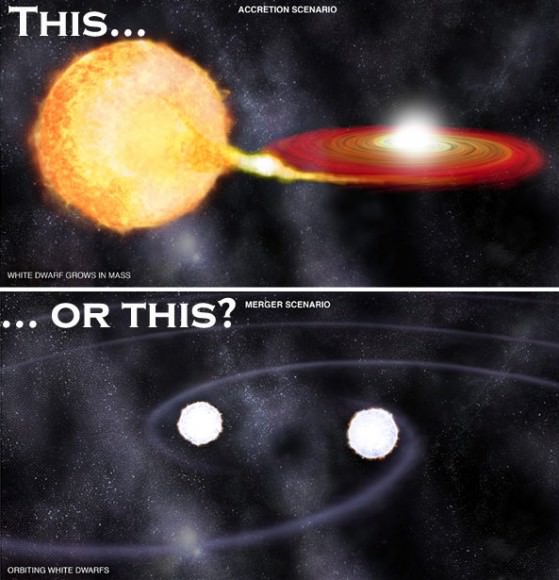

On May 31, 2011, the whole astronomy world was abuzz when SN2011dh gave both amateurs and professionals a real thrill as an easily observable event. As luck would have it, it was a binary star system being studied by the OSU team, and consisted of both a blue and red star. At this point, the astronomers surmise the red star was the one that dimmed significantly over the three-year period while the blue one blew its top. When reviewing the LBT data, the Ohio team found that when compared with Hubble images, the red star dimmed at about 10% over the final three-year period at an estimated 3% per previous years. As a curiosity, the researchers surmise the red star may have actually survived the supernova event.

“After the light from the explosion fades away, we should be able to see the companion that did not explode,” Szczygiel said.

As the team continues to collect valuable information, they estimate they could also detect another candidate set of stars at a rate of about one per year. There is also a strong possibility these detections could act as a type of test bed to predict future supernova events… looking for signals of impending doom. However, according to the news release, the Sun won’t be one to bother with.

“There’ll be no supernova for the Sun – it’ll just fizzle out,” Kochanek said. “But that’s okay – you don’t want to live around an exciting star.”

Original Story Source: Ohio State Research News.