[/caption]

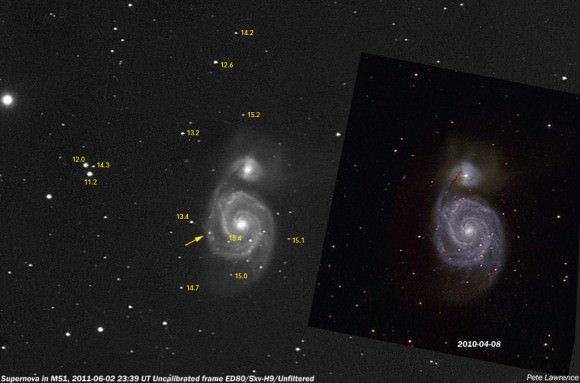

Supernovae are the brightest phenomenon in the current universe. As massive stars die as supernovae, they briefly outshine the rest of the stars in their galaxy and are visible, at least once the light gets there, from across the universe. Until recently, astronomers thought they pretty much had supernovae figured out; they could either form from the direct collapse of a massive core or the tipping over the Chandrasekhar limit as a white dwarf accreted neighbor. These methods seemed to work well until astronomers began to discover “ultra-luminous” supernovae beginning with SN 2005ap. The usual suspects could not produce such bright explosions and astronomers began looking for new methods as well as new ultra-luminous supernovae to help understand these outliers. Recently, the automated sky survey Pan-STARRS netted two more.

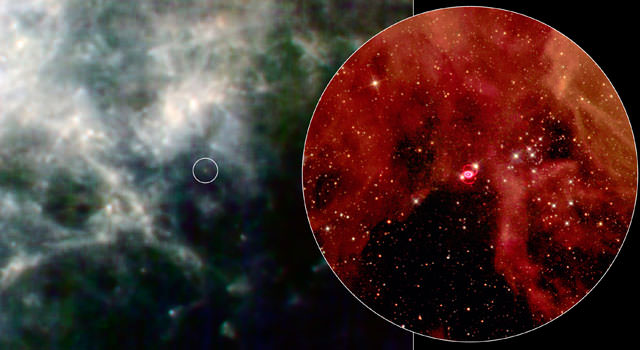

Since 2010, the Panoramic Survey Telescope & Rapid Response System (Pan-STARR) has been conducting observations atop Mount Haleakala and is controlled by the University of Hawaii. Its primary mission is to search for objects that may pose a threat to Earth. To do this, it repeatedly scans the northern sky, looking at 10 patches per night and cycling through various color filters. While it has been very successful in this area, the observations can also be used to study objects that change on short timescales such as supernovae.

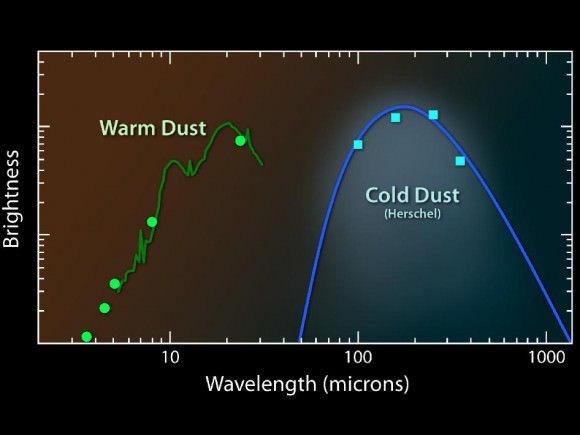

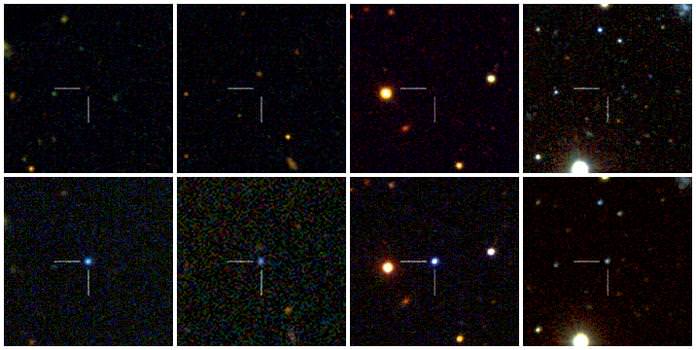

The first of the two new supernovae, PS1-10ky was already in the process of exploding as Pan-STARRS came into operation, thus, the brightness curve was incomplete since it was discovered near peak brightness and no data exists to catch it as it brightened. However, for the second, PS1-10awh, the team caught while in the process of brightening and have a complete light curve for the object. Combining the two, the team, led by Laura Chomiuk at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, was able to get a full picture of just how these titanic supernovae behave. And what’s more, since they were observed with multiple filters, the team was able to understand just how the energy was distributed. Additionally, the team was able to use other instruments, including Gemini, to get spectroscopic information.

The two new supernovae are very similar in many regards to the other ultra-luminous supernovae discovered previously, including SN 2010gx and SCP 06F6. All of these objects have been exceptionally bright with little absorption in their spectra. What little they did have was due to partially ionized carbon, silicon, and magnesium. The average peak brightness was -22.5 magnitudes where as typical core collapse supernovae peak around -19.5. The presence of these lines allowed astronomers to measure the expansion velocity for the new objects as 40,000 km/sec and place a distance to these objects as around 7 billion light years (previous ultra-luminous supernovae like these have been between 2 and 5 billion light years).

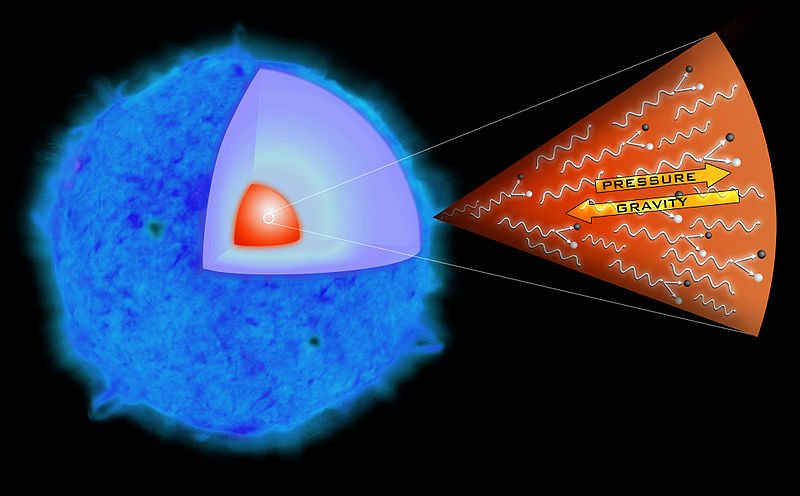

But what could power these leviathans? The team considered three scenarios. The first was radioactive decay. The violence of supernovae explosions injects atomic nuclei with additional protons and neutrons creating unstable isotopes which rapidly decay giving off visible light. This process is generally implicated in the fading out of supernovae as this decay process withers out slowly. However, based on the observations, the team concluded that it should not be possible to create sufficient amounts of the radioactive elements necessary to account for the observed brightness.

Another possibility was a rapidly rotating magnetar underwent a rapid change in its rotation. This sudden change would throw off large large chunks of material from the surface which could, in extreme cases, match the observed expansion velocity of these objects.

Lastly, the team considers a more typical supernova expanding into a relatively dense medium. In this case, the shockwave produced by the supernova would interact with the cloud around the star and the kinetic energy would heat the gas, causing it to glow. This too could reproduce many of the observed features of the supernova, but had the requirement that the star shed large amounts of material just before exploding. Some evidence is given for this as being a common occurrence in massive Luminous Blue Variable stars observed in the nearby universe. The team notes that this hypothesis may be tested by searching for radio emission as the shockwave interacted with the gas.