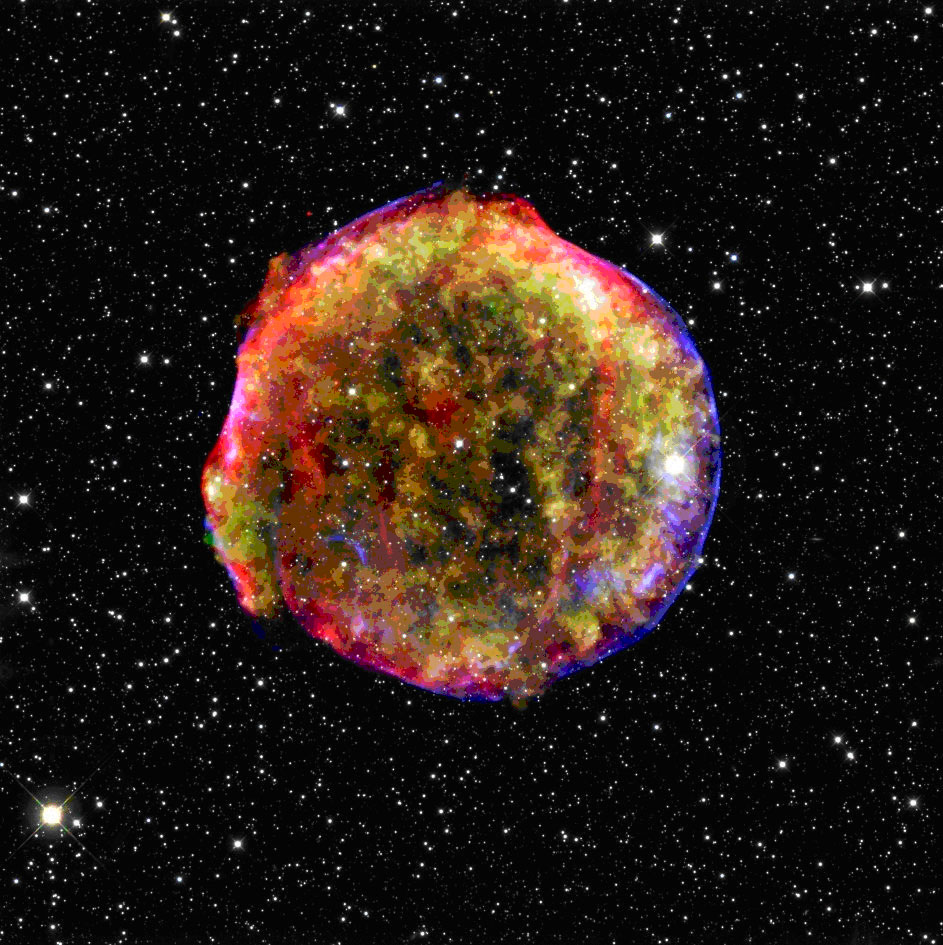

[/caption]

Based on results from a radial velocity survey, Warren Brown, (Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory) and his team have placed a few more pieces into the supernova puzzle.

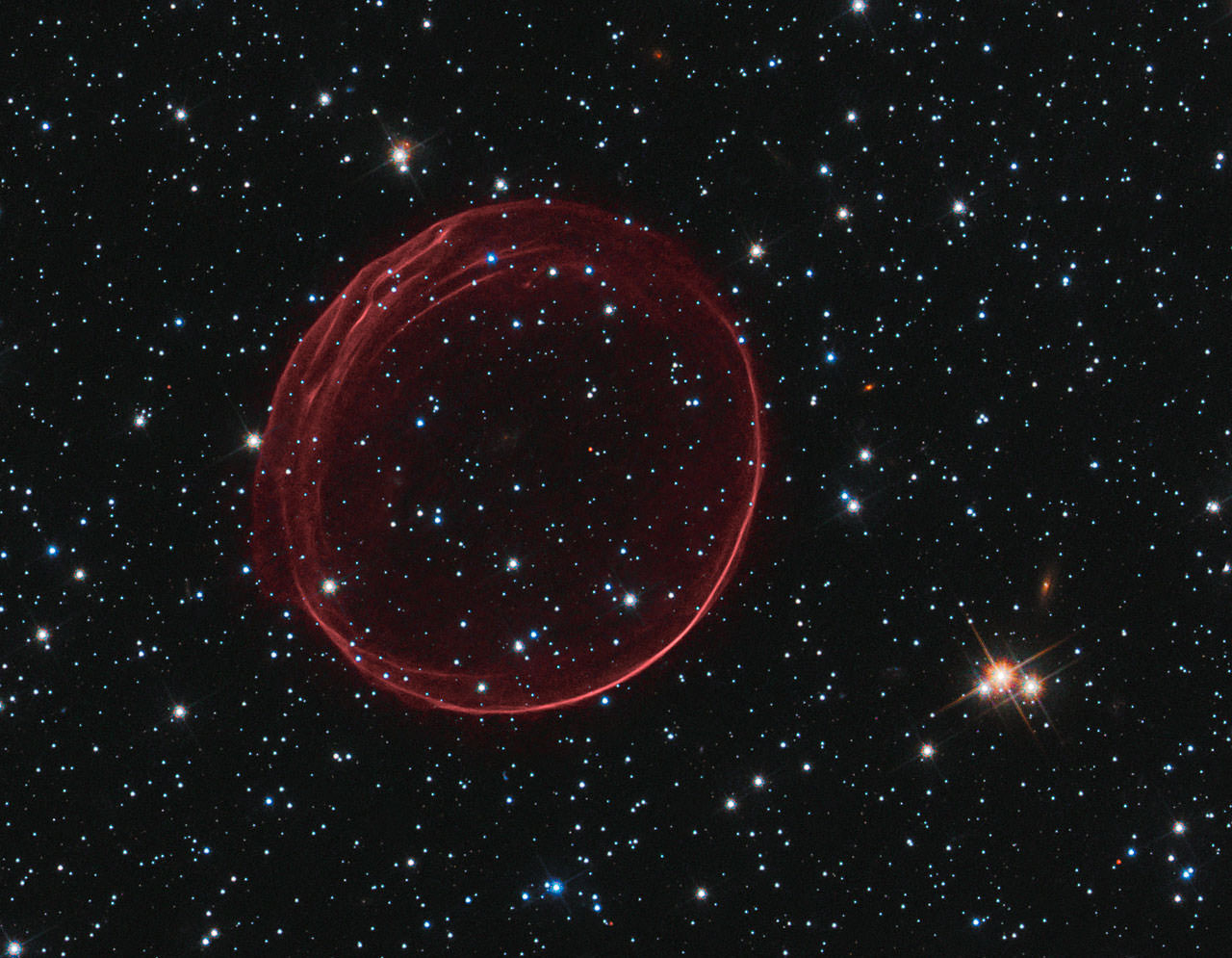

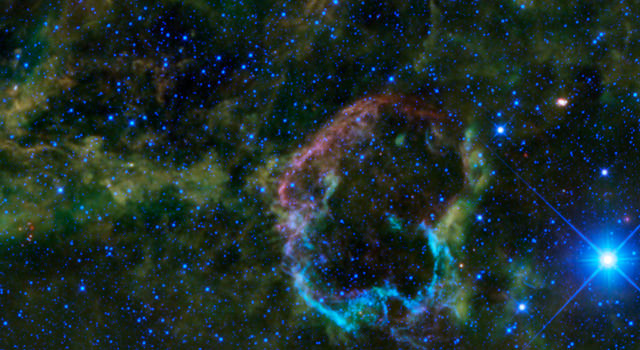

Supernovae come in many flavors. There are Type Ia, the “standard candles” everyone has heard of; and there are Type Ib and Ic, which also involve binary systems. We also have Type II supernovae that are believed to be the core collapse of single, super-massive stars. There are also super-luminous supernovae, which may be the explosive conversion of a neutron star into a quark star, and finally the weak-kneed cousins of the bunch, the under-performing underluminous supernovae.

Underluminous supernovae are a rare type of supernova explosion 10–100 times less luminous than a normal SN Type Ia and eject only 20% as much matter. Brown and his team have been investigating the connection between underluminous supernovae and merging pairs of white dwarfs.

In the 1980s, on the basis of our theoretical understanding of stellar and binary evolution it was predicted that many close double white dwarfs would exist. However, it was not until 1988 that the first one was actually discovered.

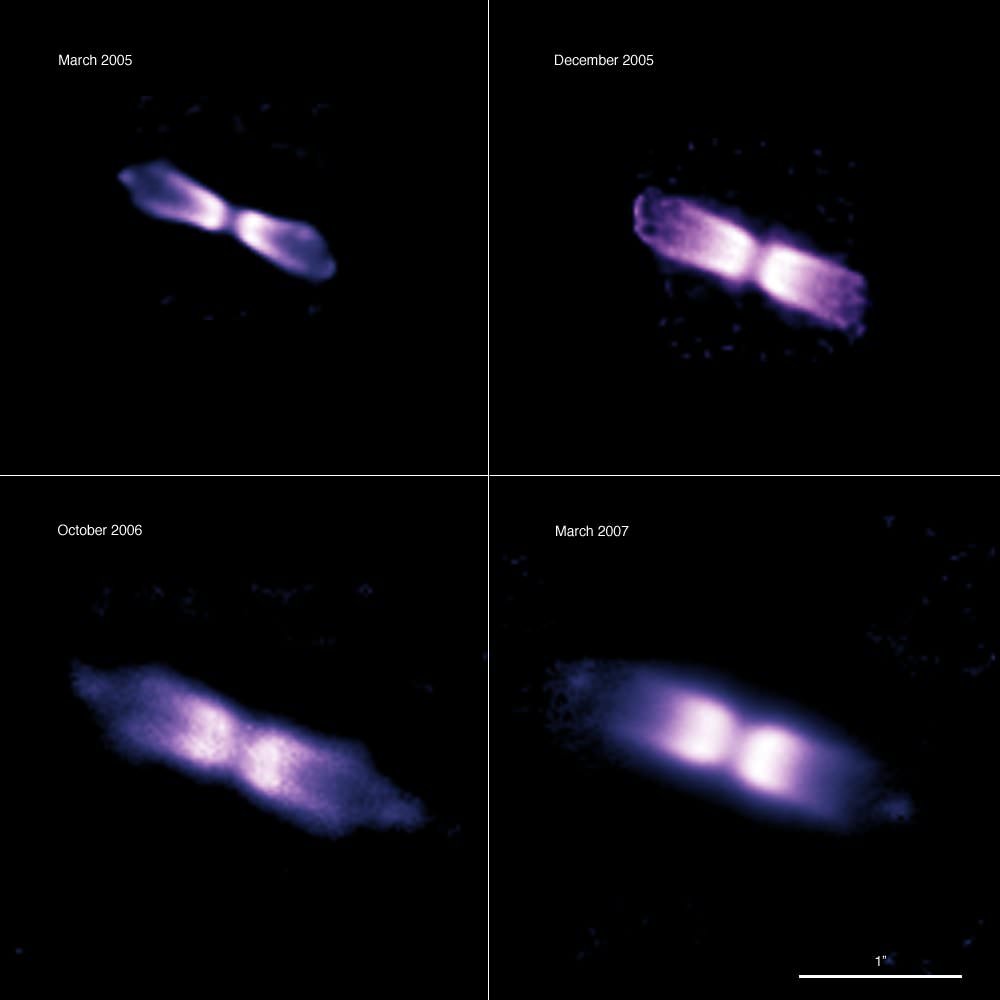

The way to find close double white dwarfs is to take high resolution spectra of the H-alpha absorption line of a white dwarf at several different times and look for variation that is caused by the orbital motion of the white dwarf around an unseen (dimmer) companion. The first systematic searches were not very unsuccessful. Only one system was found. Then, during the 1990s, Tom Marsh and collaborators concentrated their search on low-mass white dwarfs, which, based on current theories, could _only_ be formed in a binary system. In this way a dozen more systems were found.

Extremely low mass (ELM) white dwarfs (WDs) with less than 0.3 solar masses are the remnants of stars that never ignited helium in their cores. The Universe is not old enough to have produce ELM WDs by single star evolution. Therefore, ELM WDs must undergo significant mass loss sometime in their evolution. Producing WDs with 0.2 solar masses most likely requires compact binary systems.

“These white dwarfs have gone through a dramatic weight loss program,” said Carlos Allende Prieto, an astronomer at the Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias in Spain and a co-author of the study. “These stars are in such close orbits that tidal forces, like those swaying the oceans on Earth, led to huge mass losses.”

Observational data for ELM WDs is pretty hard to come by because of their rarity. For example, of the 9316 WDs identified in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, less than 0.2% have masses below 0.3 solar.

Half of the pairs discovered by Brown and collaborators are merging and might explode as supernovae in 100 million years or more.

“We have tripled the number of known, merging white-dwarf systems,” said Smithsonian astronomer and co-author Mukremin Kilic. “Now, we can begin to understand how these systems form and what they may become in the near future.” Unlike normal white dwarfs made of carbon and oxygen, these are made almost entirely of helium.

“The rate at which our white dwarfs are merging is the same as the rate of under-luminous supernovae – about one every 2,000 years,” explained Brown. “While we can’t know for sure whether our merging white dwarfs will explode as under-luminous supernovae, the fact that the rates are the same is highly suggestive.”

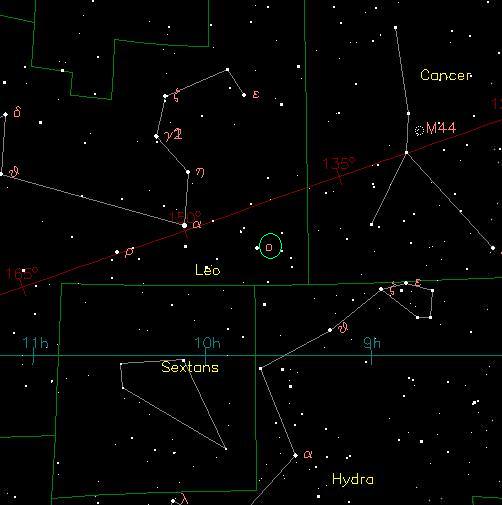

At least 25% of these ELM WDs belong to the old thick disk and halo components of the Milky Way. This helps astronomers know where to look for underluminous SNe and where they are unlikely to find them, if the models are correct. If merging ELM WD systems are the progenitors of underluminous SNe, the next generation of surveys such as the Palomar Transient Factory, Pan-STARRS, Skymapper, and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope should find them amongst the older populations of stars in both elliptical and spiral galaxies.

The papers announcing their find are available online at: http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.3047 and http://arxiv.org/abs/1011.3050.