Type Ia supernovae are an important tool for modern astronomy. They are thought to occur when a white dwarf star captures mass beyond the Chandrasekhar limit, triggering a cataclysmic explosion. Because that limit is the same for all white dwarfs, Type Ia supernovae all have about the same maximum brightness. Thus, they can be used as standard candles to determine galactic distances. Observations of Type Ia supernova led to the discovery of dark energy and that cosmic expansion is accelerating.

Continue reading “White Dwarf Measured Before it Exploded as a Supernova”Supernova Observed by Astronomers in 1181 Could Have Been a Rare Type 1ax That Leaves Behind a “Zombie Star” Remnant

In 1181 CE, Chinese and Japanese astronomers noticed a “guest star” as bright as Saturn briefly appearing in their night sky. In the thousand years since, astronomers have not been able to pinpoint the origins of that event. New observations have revealed that the “guest star” was a supernova, and a strange one at that. It was a supernova that did not destroy the star, but left behind a zombie that is still shining.

Continue reading “Supernova Observed by Astronomers in 1181 Could Have Been a Rare Type 1ax That Leaves Behind a “Zombie Star” Remnant”Shrapnel From Relatively Recent Supernovae Found in the Earth’s Crust

A Japanese oil exploration company recently dug up some samples from the Pacific Ocean floor and donated them to researchers. Those researchers, led by Dr. Anton Wallner at the Australian National University, then found the first ever evidence of a plutonium radioactive isotope that originally came from outer space. Now scientists are trying to understand what could have created that isotope, and another intriguing extraterrestrial one, and what that might have meant for Earth’s cosmic neighborhood a few million years ago.

Continue reading “Shrapnel From Relatively Recent Supernovae Found in the Earth’s Crust”Exploding Stars are Titanium Factories

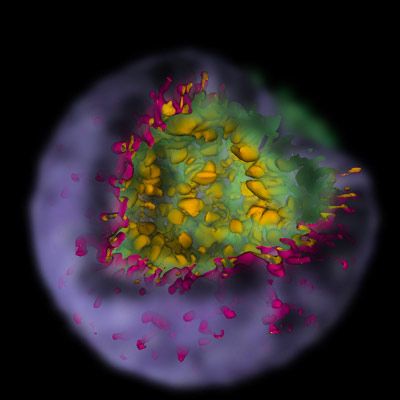

If you’re a fan of titanium, you should head to the nearest supernova. You’ll get more than enough of it. And its presence can help astronomers understand how supernovae work.

Continue reading “Exploding Stars are Titanium Factories”The Debris Cloud From a Supernova Shows an Imprint of the Actual Explosion

Computer models are continuing to play an increasing role in scientific discovery. Everything from the first moments after the Big Bang to potential for life to form on other planets has been the target of some sort of computer model. Now scientists from the RIKEN Astrophysical Big Bang Laboratory are turning this almost ubiquitous tool to a very violent event – Type Ia supernovae. Their work has now resulted in a more nuanced understanding of the effects of these important events.

Continue reading “The Debris Cloud From a Supernova Shows an Imprint of the Actual Explosion”An All-Sky X-Ray Survey Finds the Biggest Supernova Remnant Ever Seen

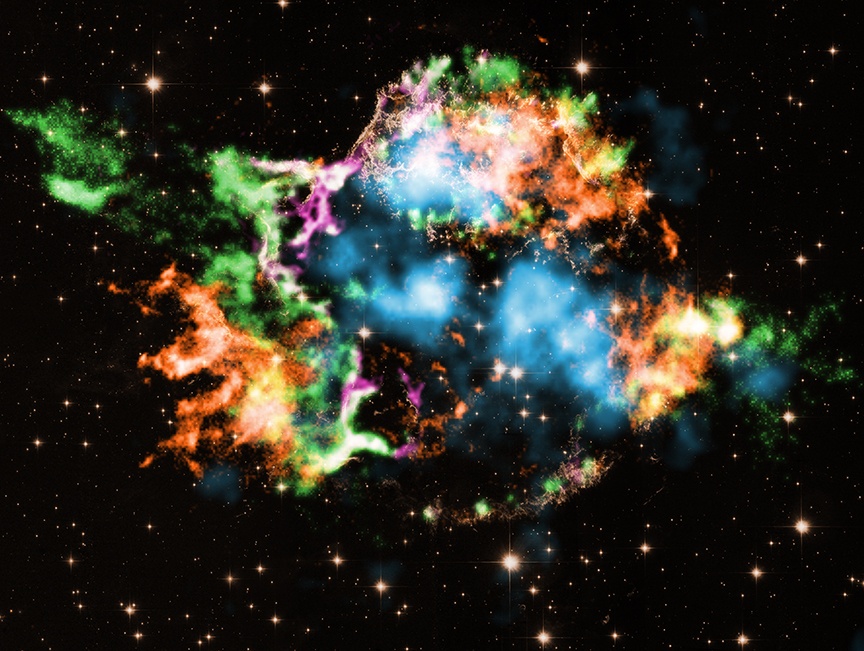

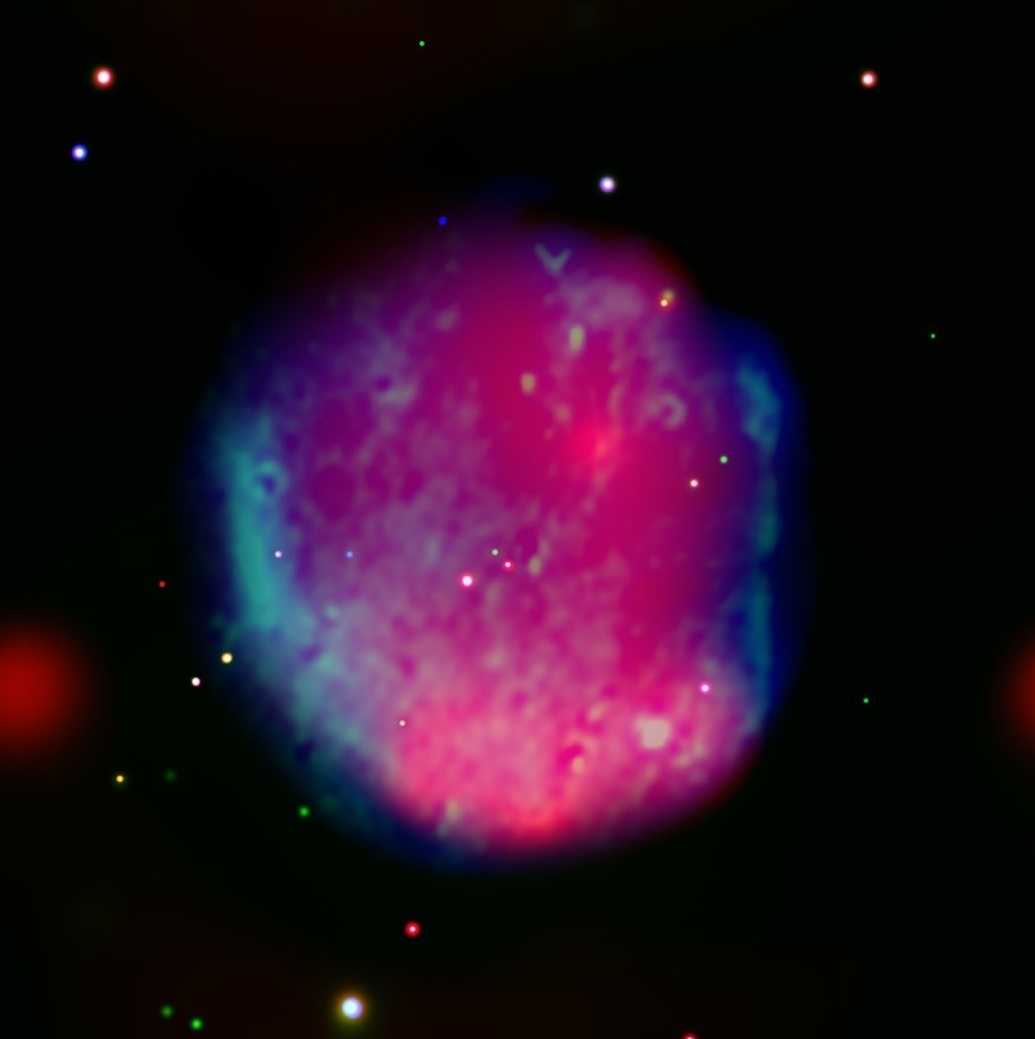

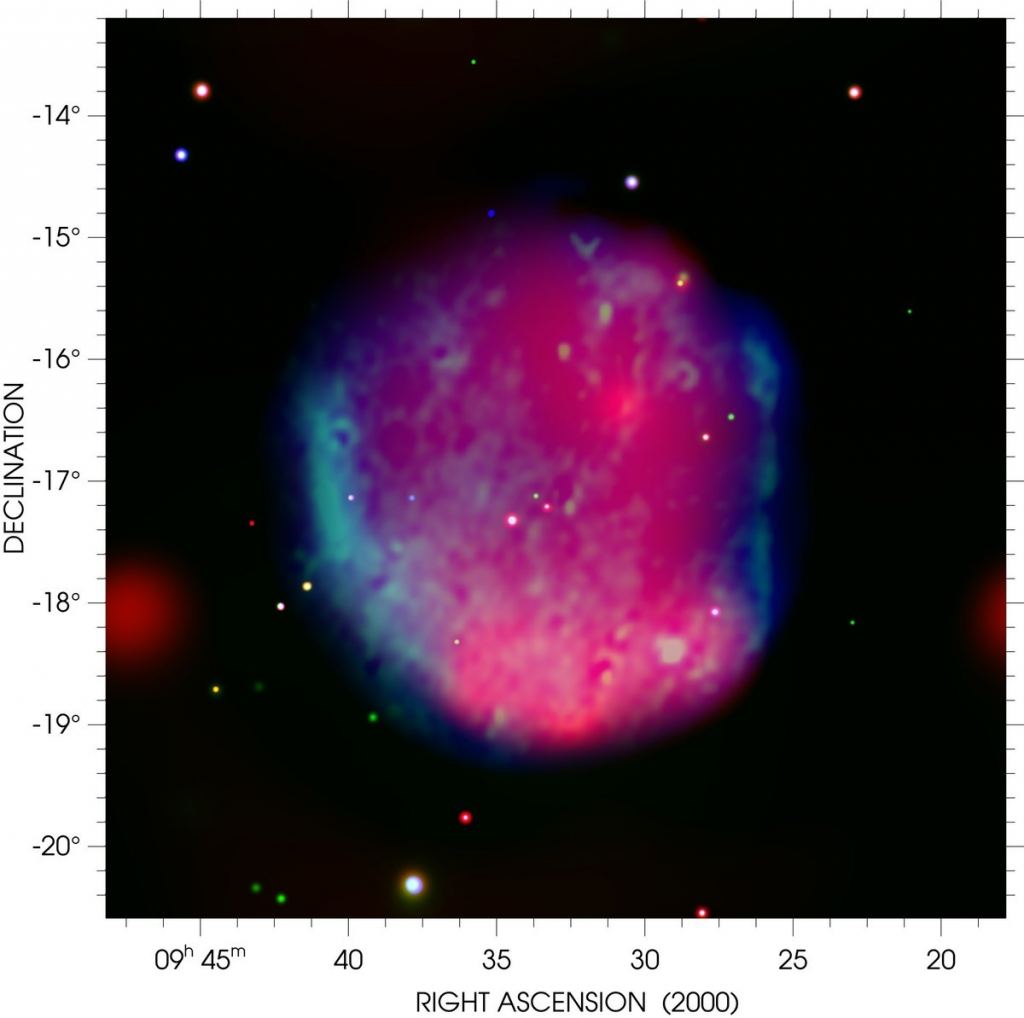

Our sky is missing supernovas. Stars live for millions or billions of years. But given the sheer number of stars in the Milky Way, we should still expect these cataclysmic stellar deaths every 30-50 years. Few of those explosions will be within naked-eye-range of Earth. Nova is from the Latin meaning “new”. Over the last 2000 years, humans have seen about seven “new” stars appear in the sky – some bright enough to be seen during the day – until they faded after the initial explosion. While we haven’t seen a new star appear in the sky for over 400 years, we can see the aftermath with telescopes – supernova remnants (SNRs) – the hot expanding gases of stellar explosions. SNRs are visible up to a 150,000 years before fading into the Galaxy. So, doing the math, there should be about 1200 visible SNRs in our sky but we’ve only managed to find about 300. That was until “Hoinga” was recently discovered. Named after the hometown of first author Scientist Werner Becker, whose research team found the SNR using the eROSITA All-Sky X-ray survey, Hoinga is one of the largest SNRs ever seen.

Credit: eROSITA/MPE (X-ray), CHIPASS/SPASS/N. Hurley-Walker, ICRAR-Curtin (Radio)

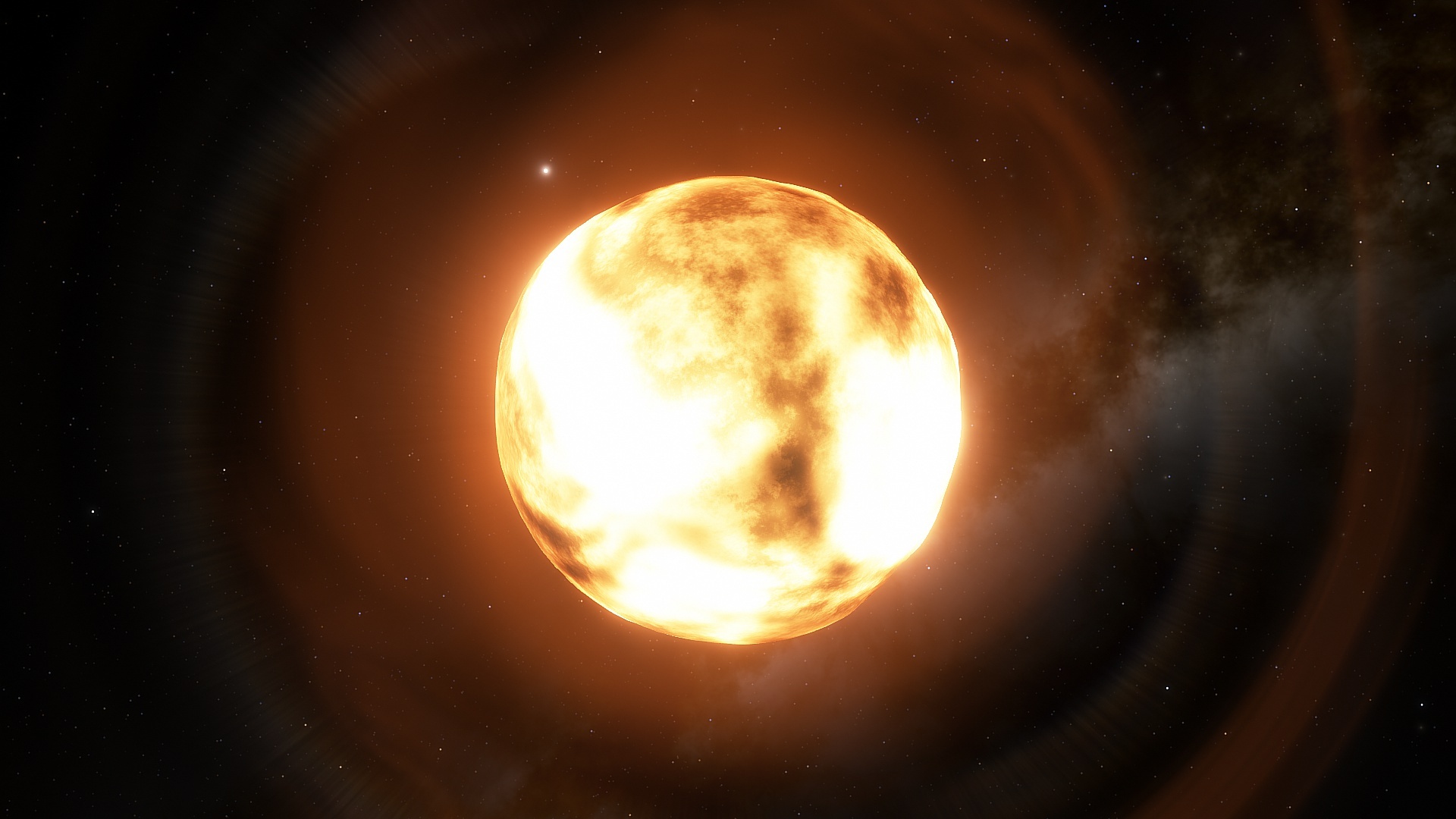

A New Study Says That Betelgeuse Won’t Be Exploding Any Time Soon

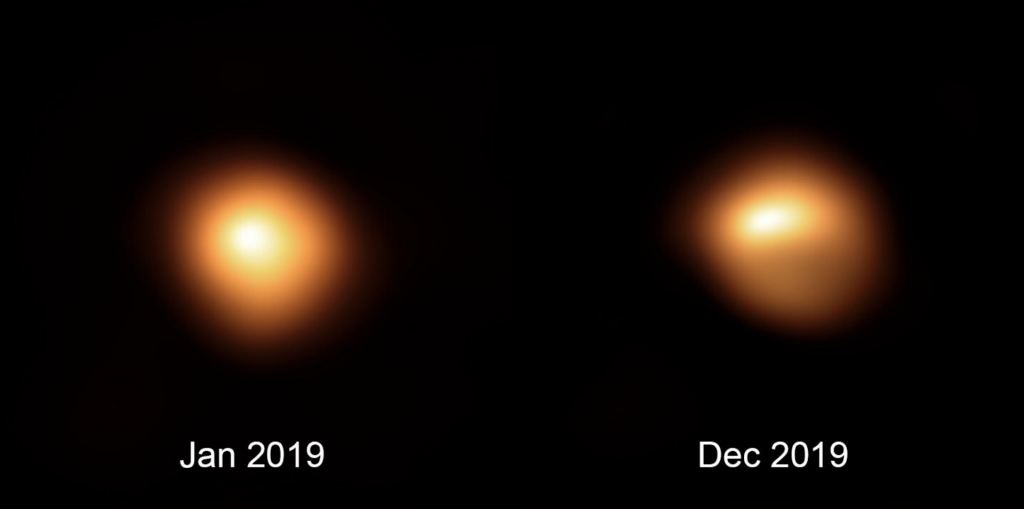

I have stood under Orion The Hunter on clear evenings willing its star Betelgeuse to explode. “C’mon, blow up!” In late 2019, Betelgeuse experienced an unprecedented dimming event dropping 1.6 magnitude to 1/3 its max brightness. Astronomers wondered – was this dimming precursor to supernova? How cosmically wonderful it would be to witness the moment Betelgeuse explodes. The star ripping apart in a blaze of light scattering the seeds of planets, moons, and possibly life throughout the Universe. Creative cataclysm.

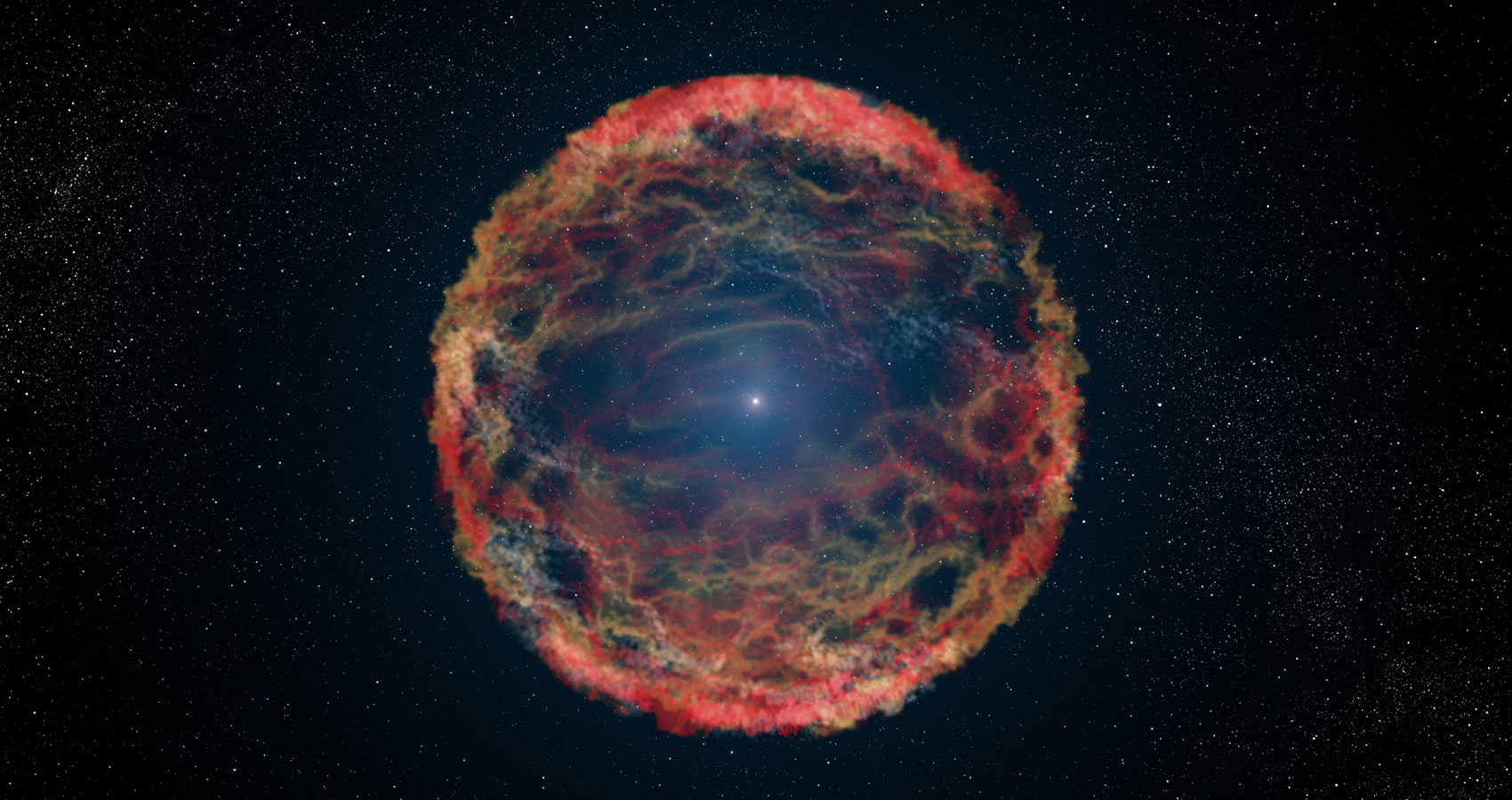

Only about ten supernova have been seen with the naked eye in all recorded history. Now we can revisit ancient astronomical records with telescopes to discover supernova remnants like the brilliant SN 1006 (witnessed in 1006AD) whose explosion created one of the brightest objects ever seen in the sky. Unfortunately, latest research suggests we all might be waiting another 100,000 years for Betelgeuse to pop. However, studying this recent dimming event gleaned new information about Betelgeuse which may help us better understand stars in a pre-supernova state.

ESO / M. Montargès et al.

Astronomers Think They’ve Found the Neutron Star Remnant Left Behind from Supernova 1987A

It was the brightest supernova in nearly 400 years when it lit the skies of the southern hemisphere in February 1987. Supernova 1987A – the explosion of a blue supergiant star in the nearby mini-galaxy known as the Large Magellanic Cloud – amazed the astronomical community. It offered them an unprecedented opportunity to observe an exploding star in real-time with modern instruments and telescopes. But something was missing. After the supernova faded, astronomers expected to find a neutron star (a hyper-dense, collapsed stellar core, made largely of neutrons) left-over at the heart of the explosion. They saw nothing.

Continue reading “Astronomers Think They’ve Found the Neutron Star Remnant Left Behind from Supernova 1987A”A New Supernova Remnant Found from an Exploding White Dwarf Star

Astronomers have spotted the remnant of a rare type of supernova explosion. It’s called a Type Iax supernova, and it’s the result of an exploding white dwarf. These are relatively rare supernovae, and astronomers think they’re responsible for creating many heavy elements.

They’ve found them in other galaxies before, but this is the first time they’ve spotted one in the Milky Way.

Continue reading “A New Supernova Remnant Found from an Exploding White Dwarf Star”There Should be a few Supernovae in the Milky Way Every Century, but we’ve Only Seen 5 in the Last 1000 Years. Why?

Our galaxy hosts supernovae explosions a few times every century, and yet it’s been hundreds of years since the last observable one. New research explains why: it’s a combination of dust, distance, and dumb luck.

Continue reading “There Should be a few Supernovae in the Milky Way Every Century, but we’ve Only Seen 5 in the Last 1000 Years. Why?”