On September 26-27 Cassini executed its latest flyby of Titan, T-86, coming within 594 miles (956 km) of the cloud-covered moon in order to measure the effects of the Sun’s energy on its dense atmosphere and determine its variations at different altitudes.

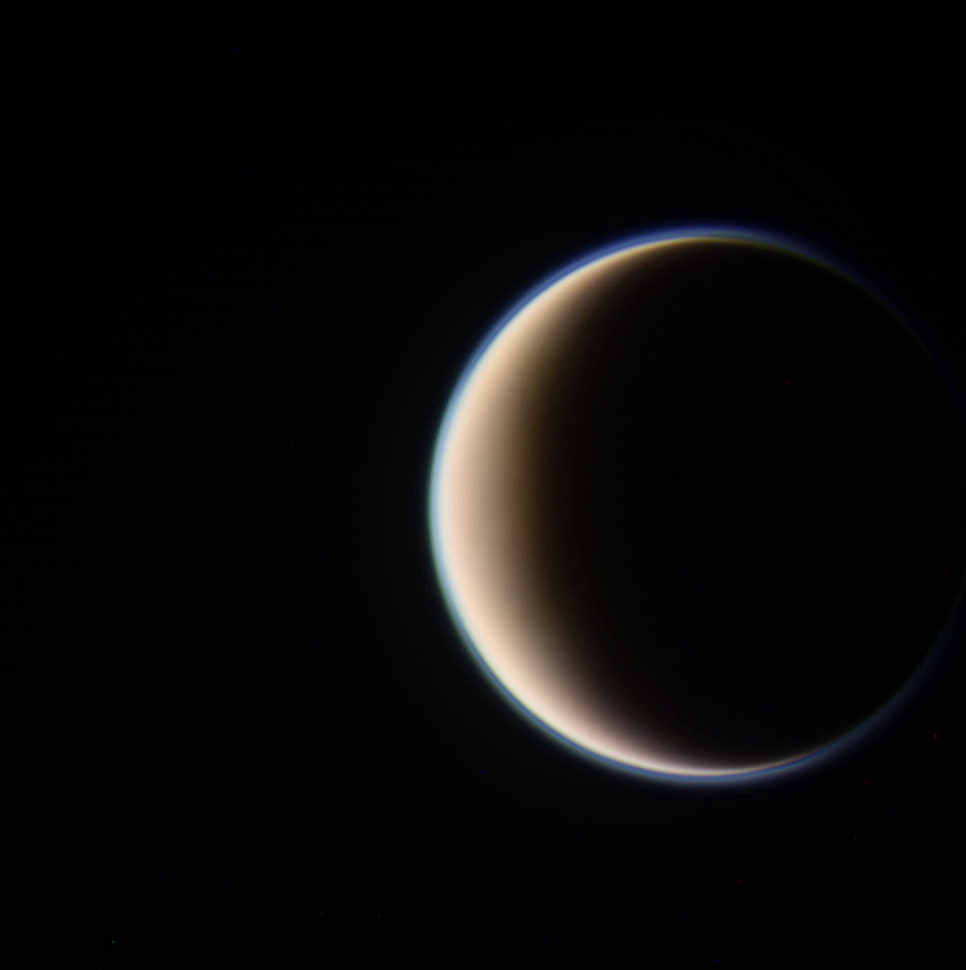

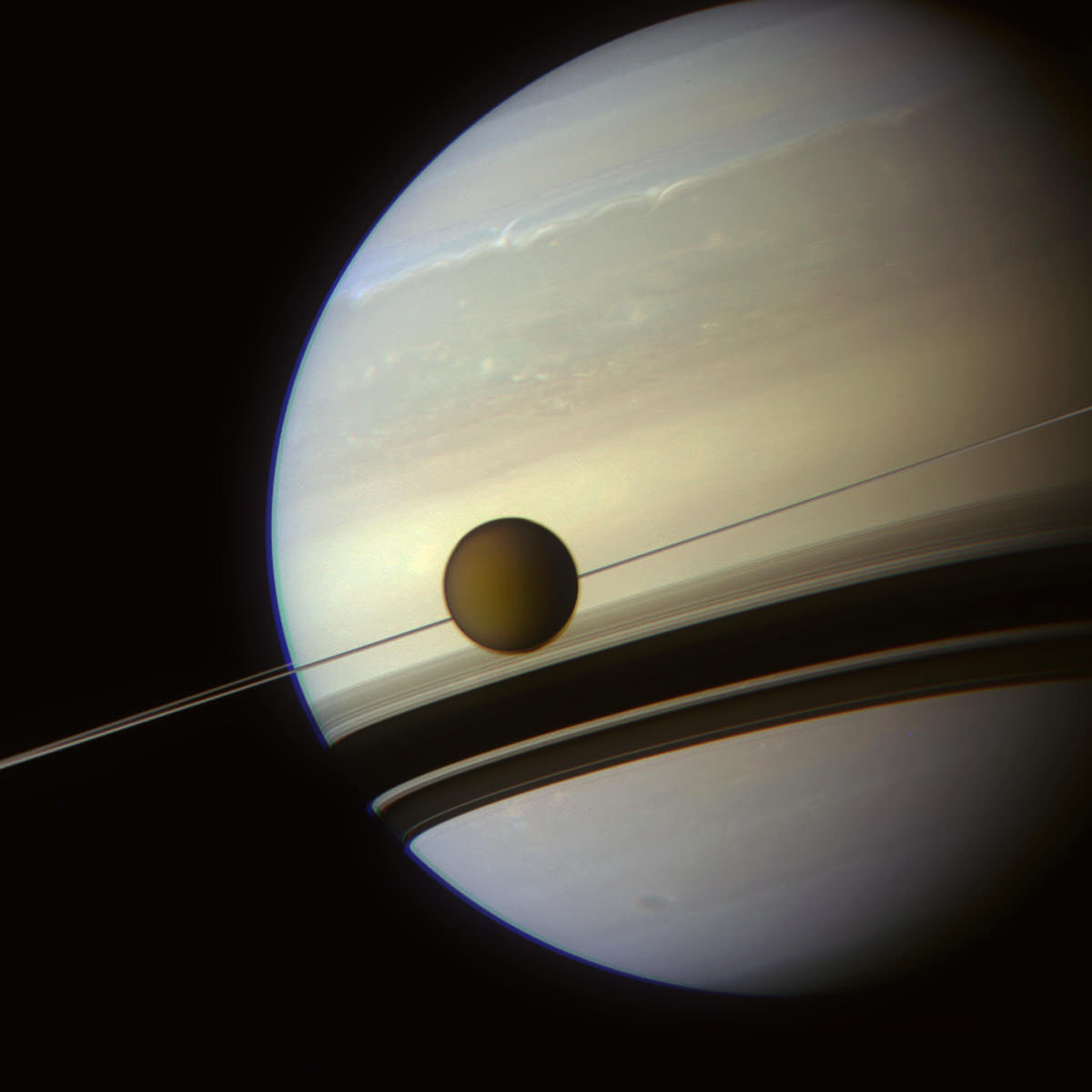

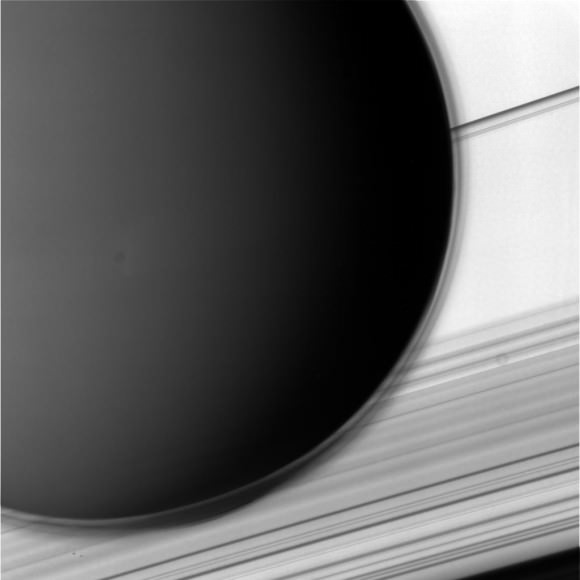

The image above was captured as Cassini approached Titan from its night side, traveling about 13,000 mph (5.9 km/s). It’s a color-composite made from three separate raw images acquired in red, green and blue visible light filters.

Titan’s upper-level hydrocarbon haze is easily visible as a blue-green “shell” above its orange-colored clouds.

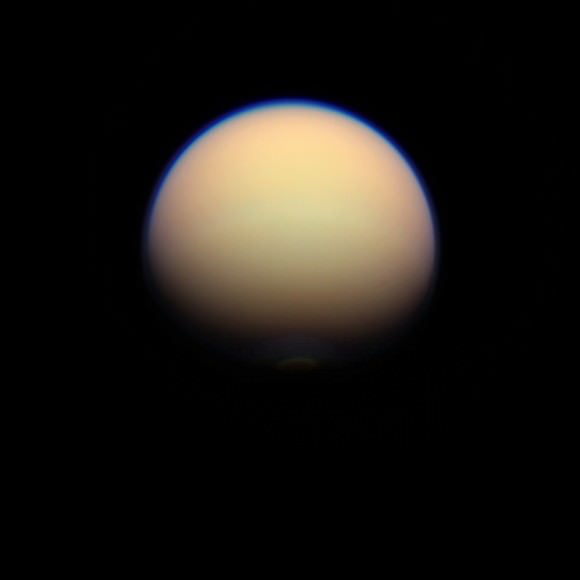

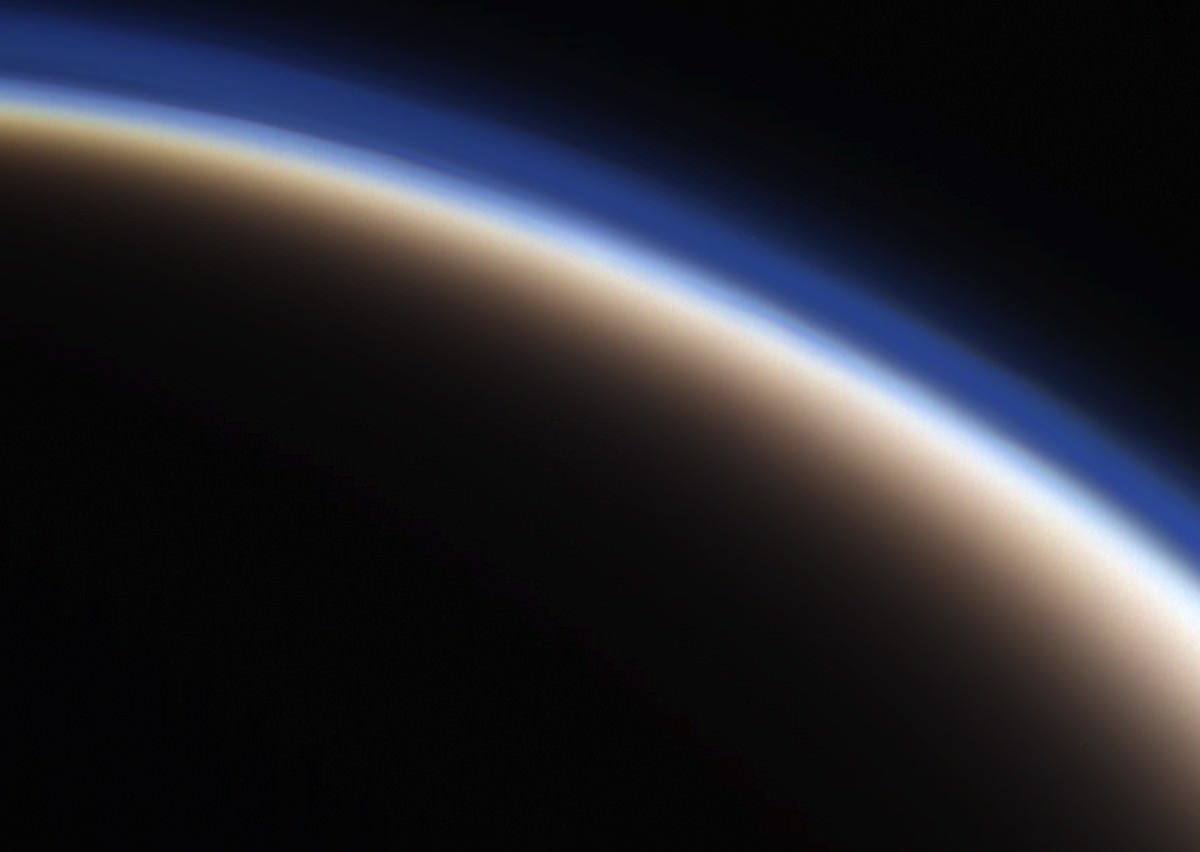

Cassini captured this image as it approached Titan’s sunlit limb, grabbing a better view of the upper haze. Some banding can be seen in its highest reaches.

The haze is the result of UV light from the Sun breaking down nitrogen and methane in Titan’s atmosphere, forming hydrocarbons that rise up and collect at altitudes of 300-400 kilometers. The sea-green coloration is a denser photochemical layer that extends upwards from about 200 km altitude.

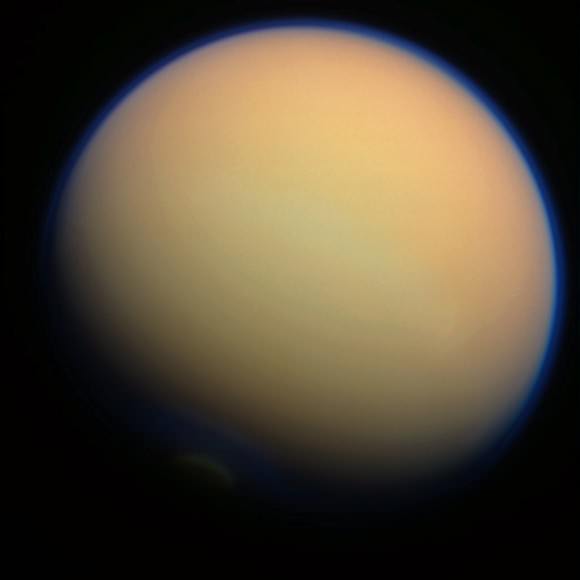

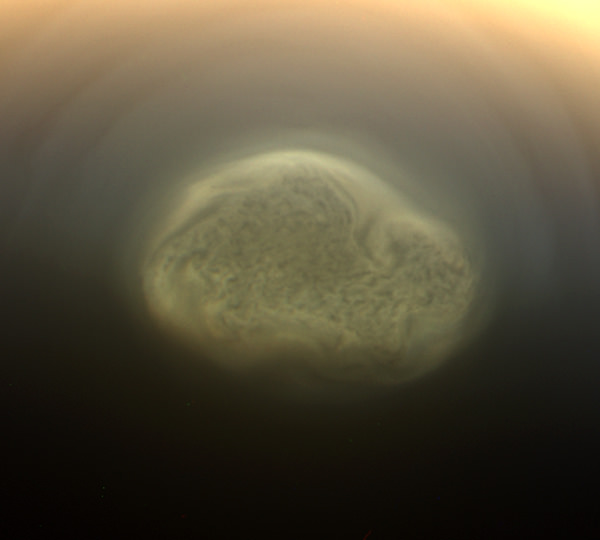

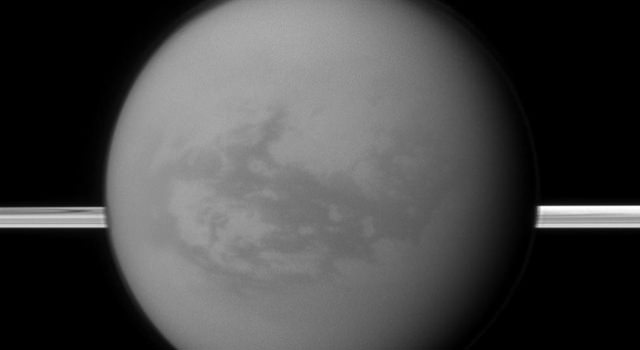

In this image, made from data acquired on Sept. 27, Titan’s south polar vortex can be made out just within the southern terminator. The vortex is a relatively new feature in Titan’s atmosphere, first spotted earlier this year. It’s thought that it’s a region of open-cell convection forming above the moon’s pole, a result of the approach of winter to Titan’s southern half.

Read: Cassini Spots Surprising Swirls Above Titan’s South Pole

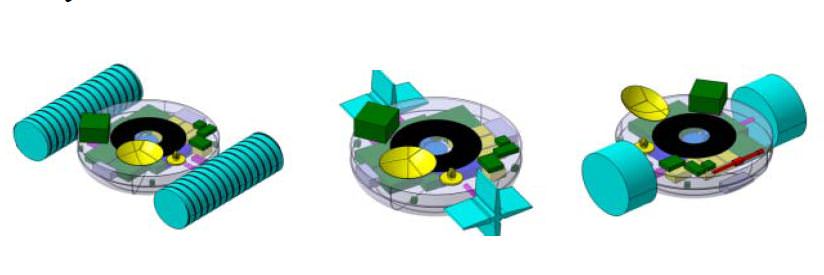

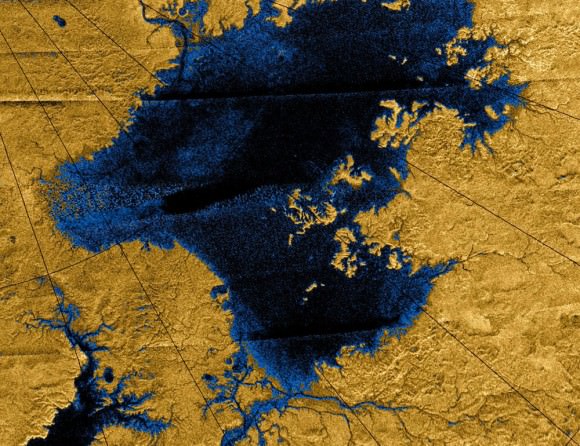

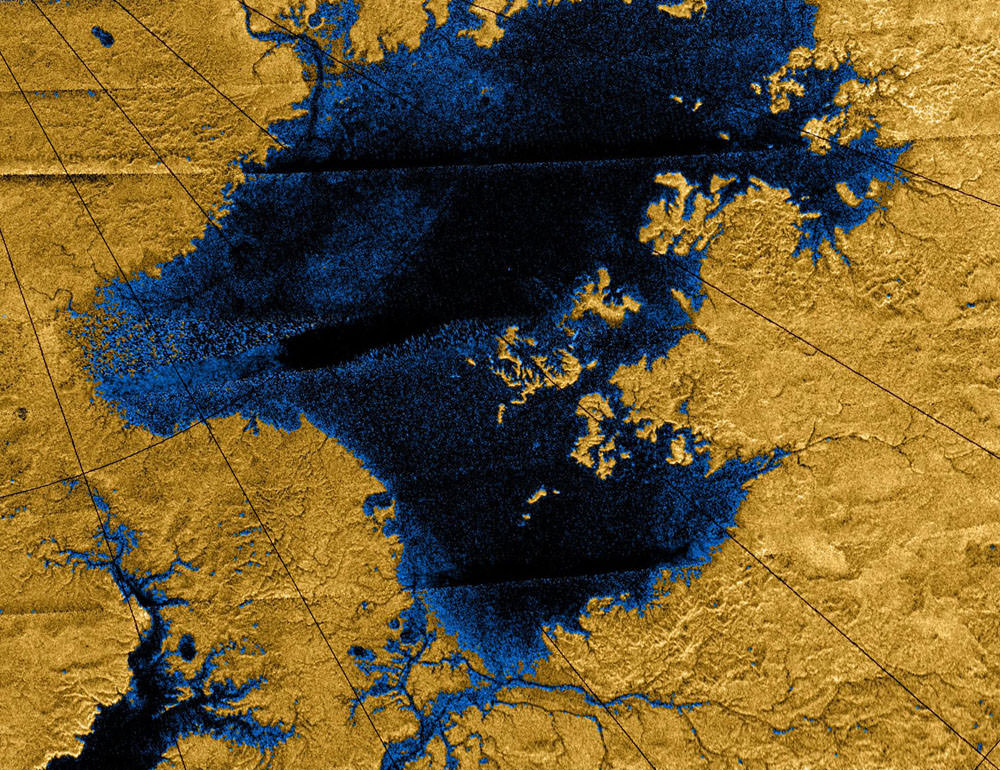

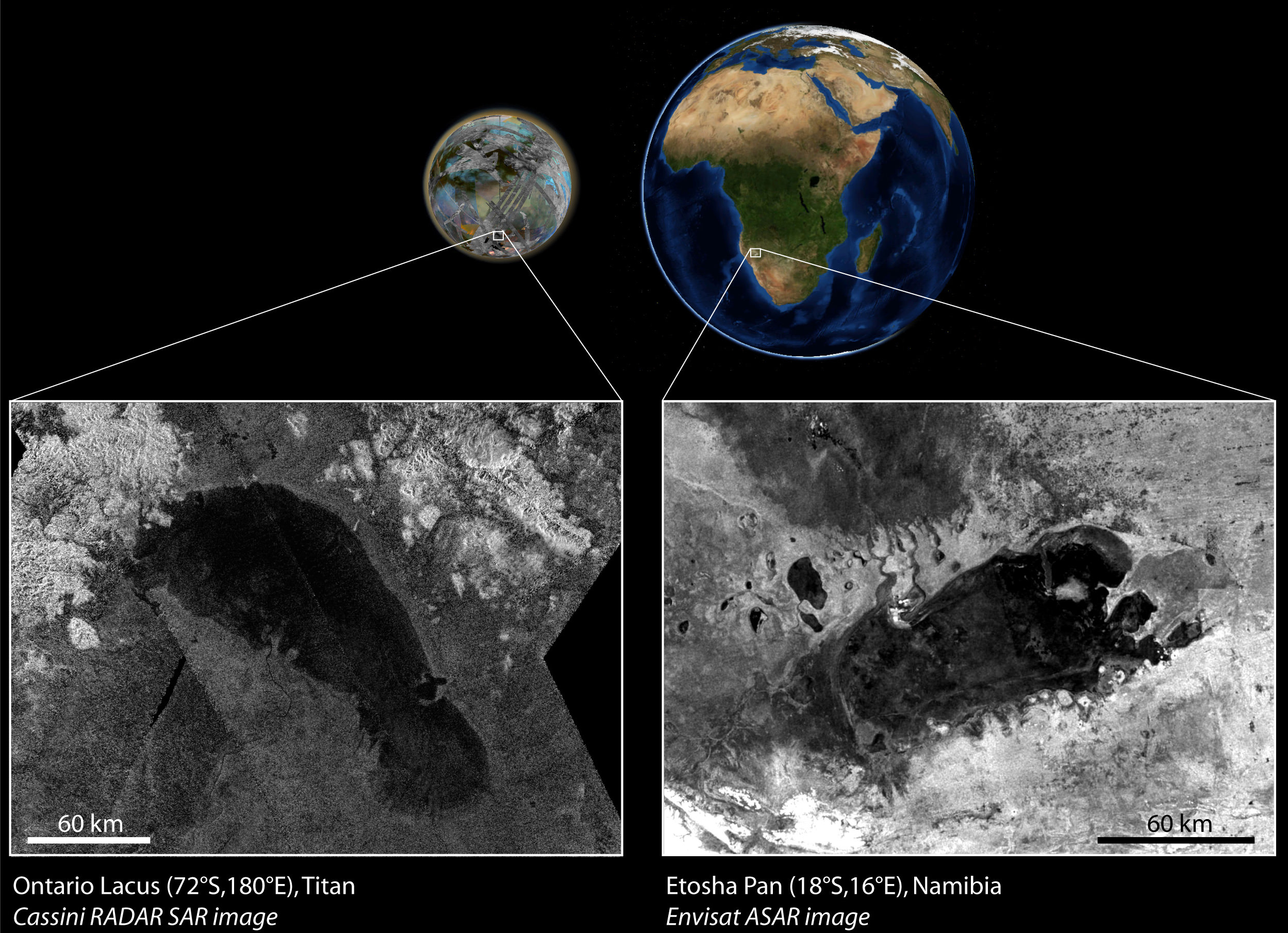

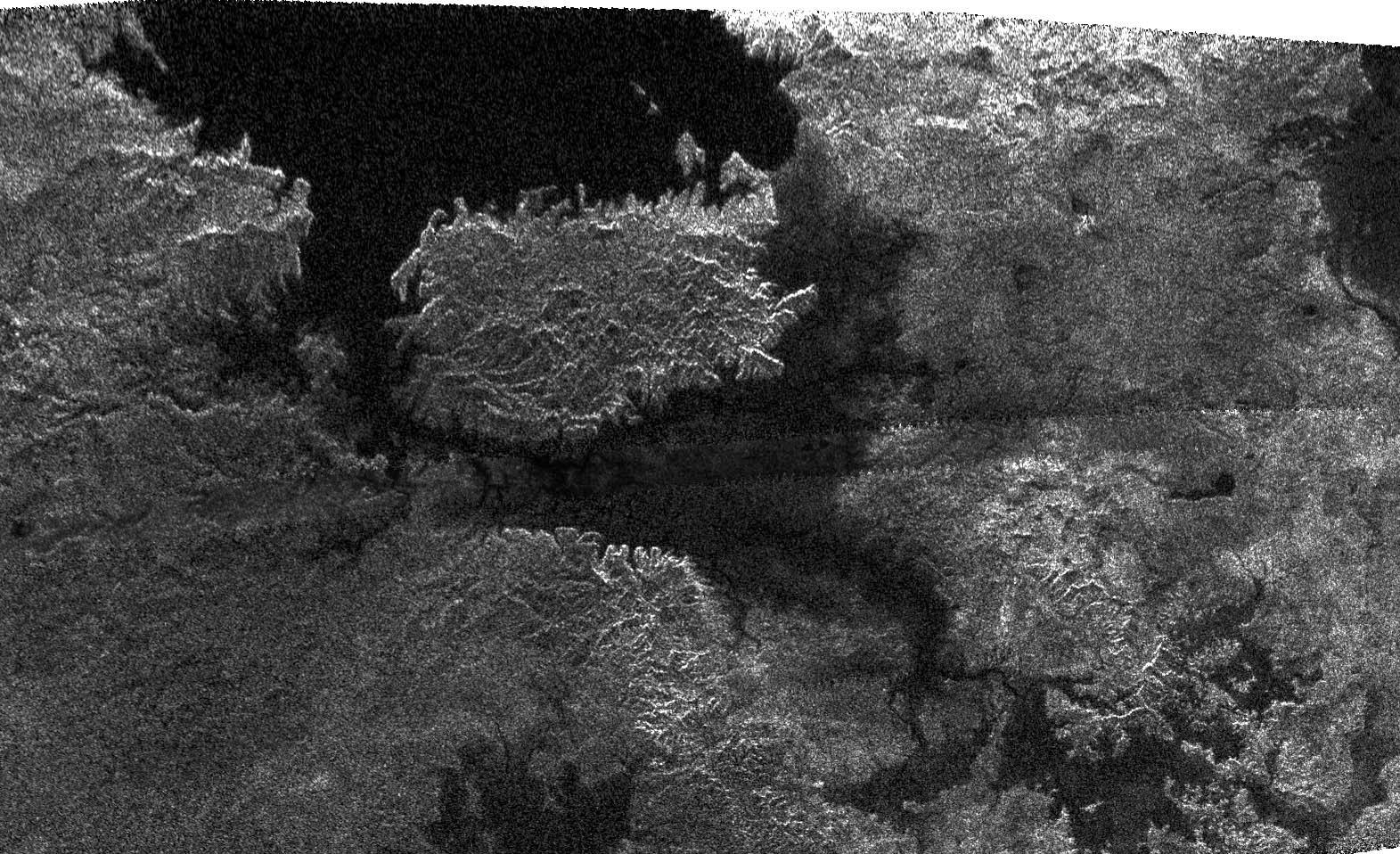

This T-86 flyby was was one of a handful of opportunities to profile Titan’s ionosphere from the outermost edge of Titan’s atmosphere. In addition Cassini was able to look for any changes to Ligeia Mare, a methane lake last observed in spring of 2007.

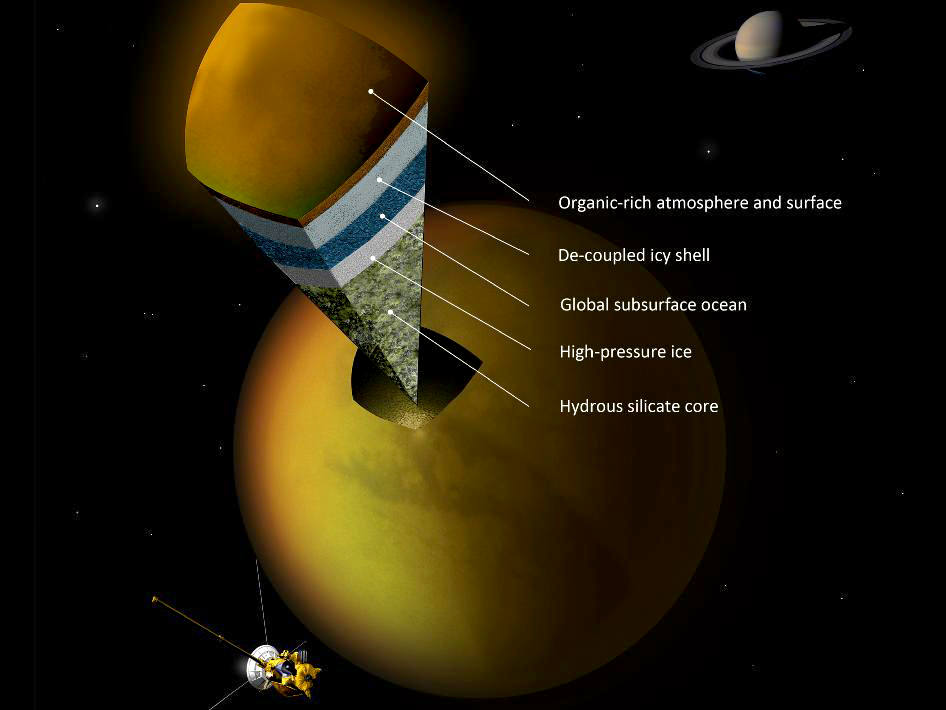

Now that Titan has been under scrutiny for a full year of Saturn’s seasons — which lasts 29.7 Earth-years — astronomers now know that varying amounts of solar radiation can drastically change situations both within Saturn’s atmosphere and on its surface.

“As with Earth, conditions on Titan change with its seasons. We can see differences in atmospheric temperatures, chemical composition and circulation patterns, especially at the poles,” said Dr. Athena Coustenis from the Paris-Meudon Observatory in France. “For example, hydrocarbon lakes form around the north polar region during winter due to colder temperatures and condensation. Also, a haze layer surrounding Titan at the northern pole is significantly reduced during the equinox because of the atmospheric circulation patterns. This is all very surprising because we didn’t expect to find any such rapid changes, especially in the deeper layers of the atmosphere.”

“It’s amazing to think that the Sun still dominates over other energy sources even as far out as Titan, over 1.5 billion kilometres from us.”

– Dr. Athena Coustenis, Paris-Meudon Observatory

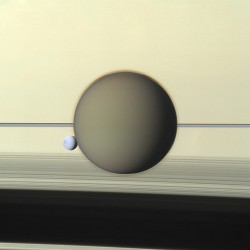

The image above, acquired on Sept. 28, was added to this post on Oct. 1. It was taken from a distance of 649,825 miles (1,045,792 kilometers.)

Cassini’s next targeted approach to Titan — T-87 — will occur on November 13.

Get more news from the Cassini mission here.

Image credits: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute. All color composites by Jason Major. Images have not been validated or calibrated by the SSI team.

(Do you love the Cassini mission as much as we do? Vote on your favorite Cassini “Shining Moment” here, in honor of the 15th anniversary of Cassini’s launch on October 15! Amazing to think it’s already been 15 years — 8 of those in orbit around Saturn!)