[/caption]

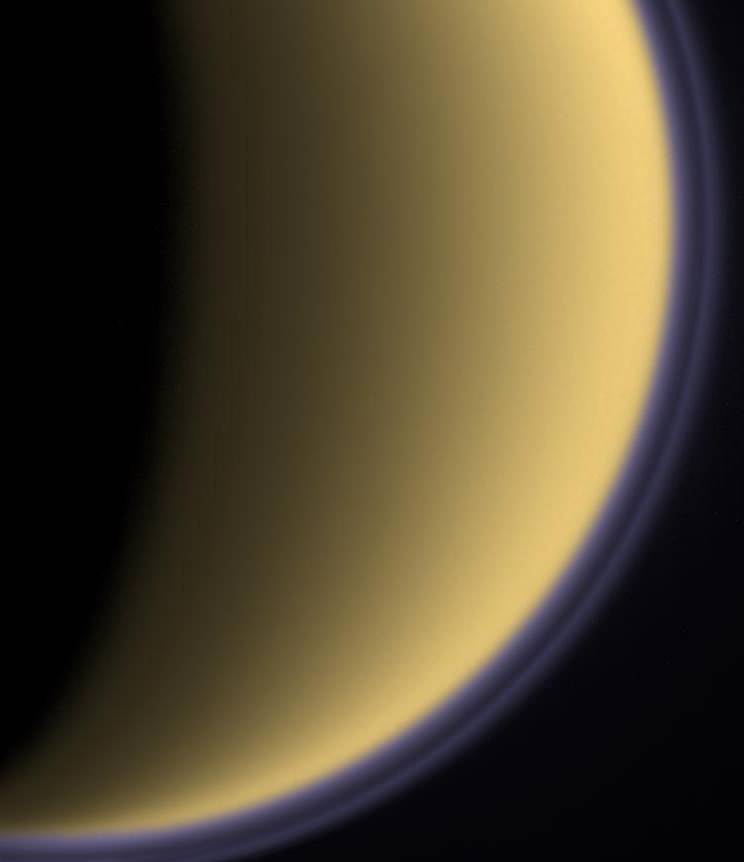

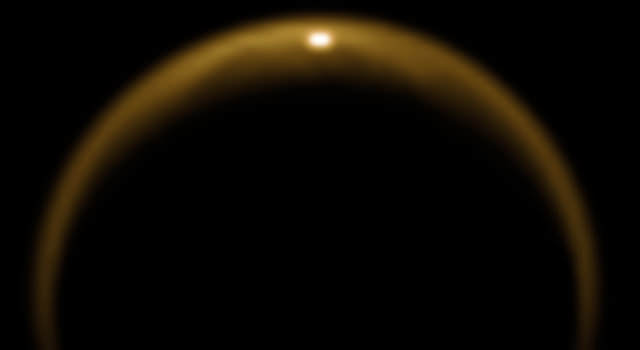

Two papers released last week detailing oddities found on Titan have blown the top off the ‘jumping to conclusions’ meter, and following media reports of NASA finding alien life on Saturn’s hazy moon, scientists are now trying to put a little reality back into the news. “Everyone: Calm down!” said Cassini imaging team leader Carolyn Porco on Twitter over the weekend. “It is by NO means certain that microbes are eating hydrogen on Titan. Non-bio explanations are still possible.” Porco also put out a statement on Monday saying such reports were “the unfortunate result of a knee-jerk rush to sensationalize an exciting but rather complex, nuanced and emotionally-charged issue.”

Astrobiologist Chris McKay told Universe Today that life on Titan is “certainly the most exciting, but it’s not the simplest explanation for all the data we’re seeing.”

McKay suggests everyone needs to take the Occam’s Razor approach, where the simplest theory that fits the facts of a problem is the one that should be selected.

The two papers suggest that hydrogen and acetylene are being depleted at the surface of Titan. The first paper by Darrell Strobel shows hydrogen molecules flowing down through Titan’s atmosphere and disappearing at the surface. This is a disparity between the hydrogen densities that flow down to the surface at a rate of about 10,000 trillion trillion hydrogen molecules per second, but none showing up at the surface.

“It’s as if you have a hose and you’re squirting hydrogen onto the ground, but it’s disappearing,” Strobel said. “I didn’t expect this result, because molecular hydrogen is extremely chemically inert in the atmosphere, very light and buoyant. It should ‘float’ to the top of the atmosphere and escape.”

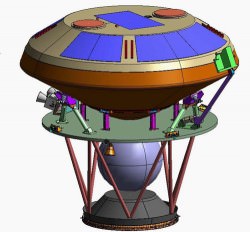

The other paper (link not yet available) led by Roger Clark, a Cassini team scientist, maps hydrocarbons on Titan’s surface and finds a surprising lack of acetylene. Models of Titan’s upper atmosphere suggest a high level of acetylene in Titan’s lakes, as high as 1 percent by volume. But this study, using the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) aboard Cassini, found very little acetylene on Titan’s surface.

Of course, one explanation for both discoveries is that something on Titan is consuming the hydrogen and acetylene.

Even though both findings are important, McKay feels the crux of any possible life on Titan hinges on verifying Strobel’s discovery about the lack of hydrogen.

“To me, the whole thing hovers on this determination of whether there is this flux of hydrogen is real,” McKay said via phone. “The acetylene has been missing and the ethane has been missing, but that certainly doesn’t generate a lot of excitement, because how much is supposed to be there depends on how much is being made. There are a lot of uncertainties.”

McKay stressed both results are still preliminary and the hydrogen loss in particular is the result of a computer calculation, and not a direct measurement. “It is the result of a computer simulation designed to fit measurements of the hydrogen concentration in the lower and upper atmosphere in a self-consistent way,” he said in a statement he put out over the weekend. “It is not presently clear from Strobel’s results how dependent his conclusion of a hydrogen flux into the surface is on the way the computer simulation is constructed or on how accurately it simulates the Titan chemistry.”

However, the findings are interesting for astrobiology, and would require the actual existence of methane-based life, a theory McKay himself proposed five years ago, which he described today as an “odd idea.”

In 2005, McKay and Heather Smith (McKay and Smith, 2005) suggested that methane-based life (rather than water-based) called methanogens on Titan could consume hydrogen, acetylene, and ethane. The key conclusion of that paper was “The results of the recent Huygens probe could indicate the presence of such life by anomalous depletions of acetylene and ethane as well as hydrogen at the surface.”

Even though the two new papers seem to show evidence for all three of these on Titan, McKay said this is a still a long way from “evidence of life”. However, it is extremely interesting.

But what does McKay really think?

“Unfortunately, if I was betting, the most likely explanation is that Darrel’s (Strobel) results are wrong and that further analysis will show there is another explanation for the data he is trying to fit, besides the strong flux of hydrogen into the surface. I would be very happy if we did confirm all that data, but we do have to take it in steps.”

McKay provided four possibilities for the recently reported findings, listed in order of their likely reality:

1. The determination that there is a strong flux of hydrogen into the surface is mistaken. “It will be interesting to see if other researchers, in trying to duplicate Strobel’s results, reach the same conclusion,” McKay said.

2. There is a physical process that is transporting H2 from the upper atmosphere into the lower atmosphere. One possibility is adsorption onto the solid organic atmospheric haze particles which eventually fall to the ground. However this would be a flux of H2, and not a net loss of H2.

3. If the loss of hydrogen at the surface is correct, the non-biological explanation requires that there be some sort of surface catalyst, presently unknown, that can mediate the hydrogenation reaction at 95 K, the temperature of the Titan surface. “That would be quite interesting and a startling find although not as startling as the presence of life,” McKay said.

4. The depletion of hydrogen, acetylene, and ethane, is due to a new type of liquid-methane based life form as predicted (Benner et al. 2004, McKay and Smith 2005, and Schulze-Makuch and Grinspoon 2005 (Astrobiology, vol. 5, no. 4., p. 560-567.).

McKay said if further analysis shows that a strong flux of hydrogen into the surface really is happening, “then my first two explanations are no longer options and we are then left with two really quite remarkable alternatives, either there is some mysterious metalysis going on, which at 95 k is really hard to imagine, and would have enormous implications for things like chemical engineering. And the second alternative is that there is life, which is even more amazing.”

“So to make process on this,” McKay continued, “we have to confirm Darrel’s result that there is hydrogen being fluxed onto the surface of Titan, that is really way unexpected, and unfortunately, it constitutes extraordinary claims that need extraordinary evidence. Darrel’s paper is just a first step in that.”

What does McKay think about the rash of media reports claiming life on Titan?

“Well, I think it reflects our human fascination and desire to find life out there,” he said. “We want it to be true. When we’re given a set of facts, if they are consistent with biology we jump to that explanation first. The most biologically interesting explanation is the first one we look to. We ought to give that a name — something like ‘Carl Sagan’s Razor’ as opposed to ‘Occam’s Razor,’ which would say that ‘The most exciting explanation is assumed to be true until it is proven false.'”

You can read all of McKay’s written response on the CICLOPS website, which Porco said will be “the first installment in a new feature on the CICLOPS website, called ‘Making Sense of the News’, where from time to time, scientists, both involved in Cassini and not, will be invited to comment on new developments that bear on the exploration of the solar system and the study of planetary systems, including our own.”