[/caption]

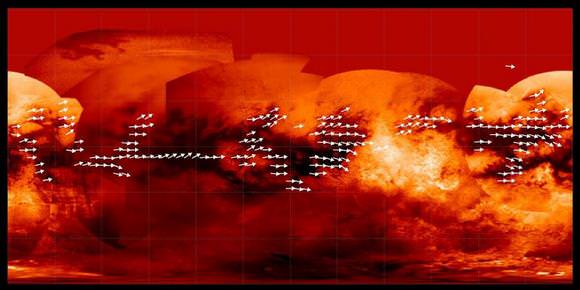

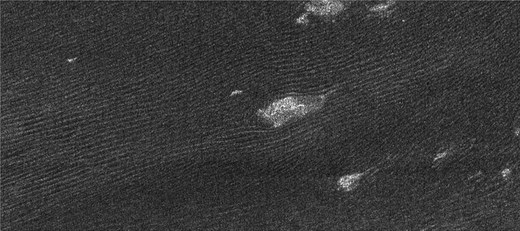

Once every 15 years, Saturn flashes its paper-thin rings in edge-on formation relative to Earth.

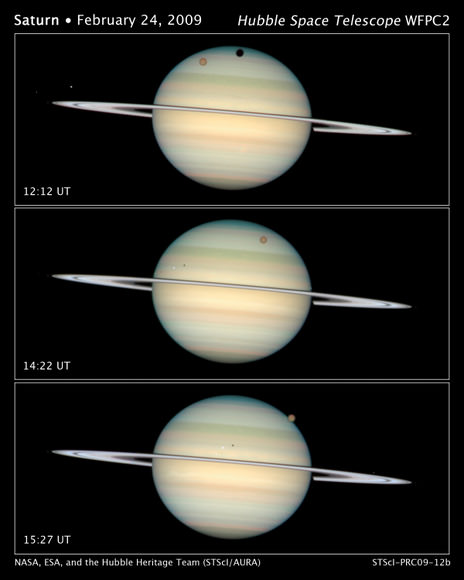

Because the orbits of Saturn’s major satellites are in the ring plane, too, this alignment gives astronomers a rare opportunity to capture a spectacular parade of celestial bodies crossing Saturn’s surface.

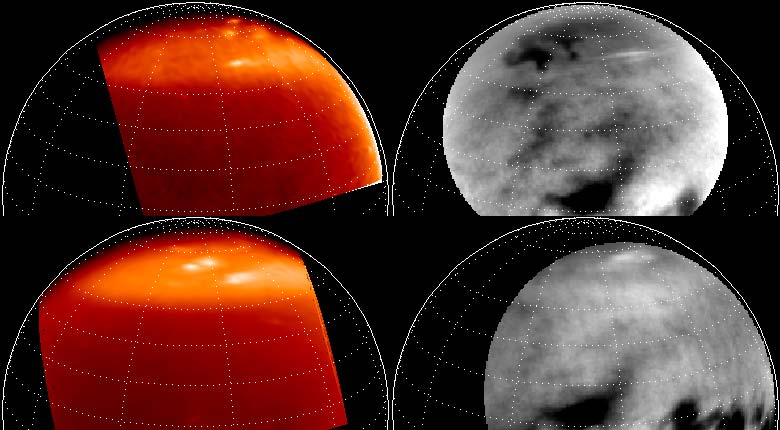

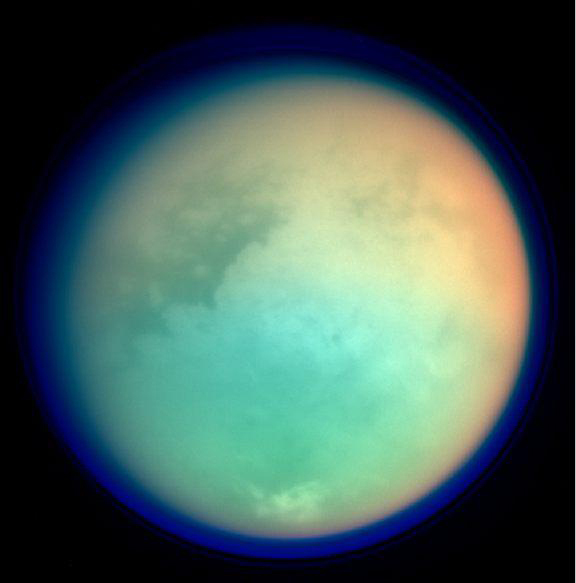

Leading this moon train is Titan – larger than the planet Mercury. The frigid moon’s thick nitrogen atmosphere is tinted orange with the smoggy byproducts of sunlight interacting with methane and nitrogen. Several of the much smaller icy moons that are closer in to the planet line up along the upper edge of the rings.

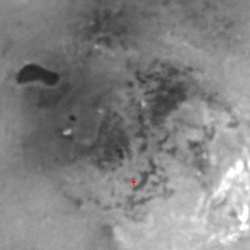

In the image, snapped by the Hubble Space Telescope on February 24, the giant orange moon Titan casts a large shadow onto Saturn’s north polar hood. Below Titan, near the ring plane and to the left is the moon Mimas, casting a much smaller shadow onto Saturn’s equatorial cloud tops. Farther to the left, and off Saturn’s disk, are the bright moon Dione and the fainter moon Enceladus.

Hubble’s exquisite sharpness also reveals Saturn’s banded cloud structure, which is similar to Jupiter’s.

At the time, Saturn was at a distance of roughly 775 million miles (1.25 billion kilometers) from Earth. Hubble can see details as small as 190 miles (300 km) across on Saturn. The dark band running across the face of the planet slightly above the rings is the shadow of the rings cast on the planet.

Early 2009 was a favorable time for viewers with small telescopes to watch moon and shadow transits crossing the face of Saturn. Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, crossed Saturn on four separate occasions: January 24, February 9, February 24, and March 12, although not all events were visible from all locations on Earth.

This “ring plane crossing” occurs every 14-15 years. In 1995-96 Hubble witnessed the ring plane crossing event, as well as many moon transits, and even helped discover several new moons of Saturn.

Source (and more images!): HubbleSite