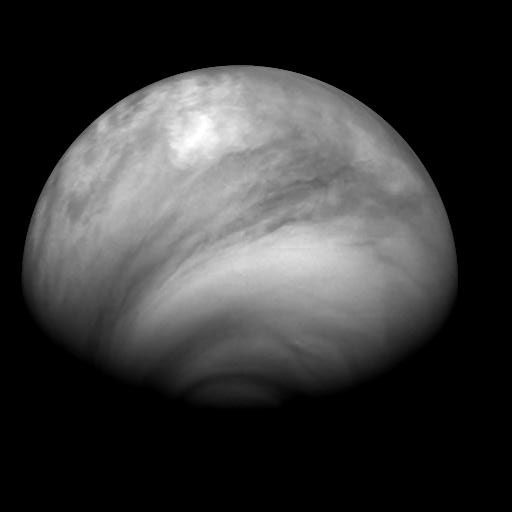

Every day brings on new discoveries and now ESA’s Venus Express spacecraft has delivered another… the red-hot planet has an ozone layer. Located high in the Venusian atmosphere, this planetary property will help us further understand how such features compare to Earth and Mars – along with refining our search for extra-terrestrial life.

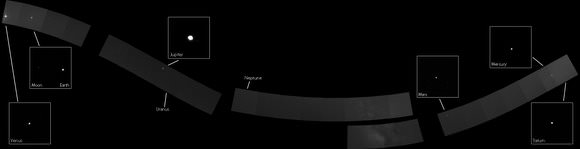

This wonderful discovery was made while Venus Express was busy watching stars at the periphery. When seen through the planet’s atmosphere, the SPICAV instrument was able to distinguish gas types spectroscopically. By picking apart the wavelengths, ozone was detected through its absorption of ultraviolet light. It forms when sunlight breaks down the carbon dioxide molecules and releases oxygen. From there, they are distributed by planetary winds where the oxygen atoms will either combine into two-atom oxygen molecules, or form three-atom ozone.

“This detection gives us an important constraint on understanding the chemistry of Venus’ atmosphere,” says Franck Montmessin, who led the research.

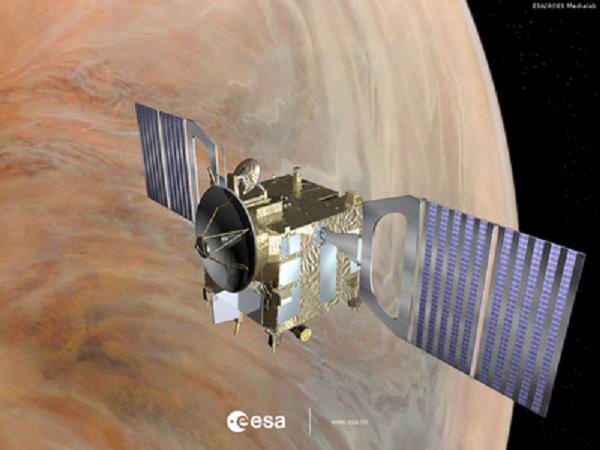

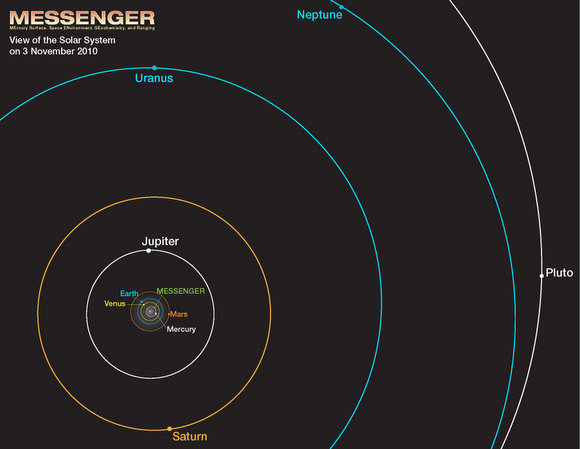

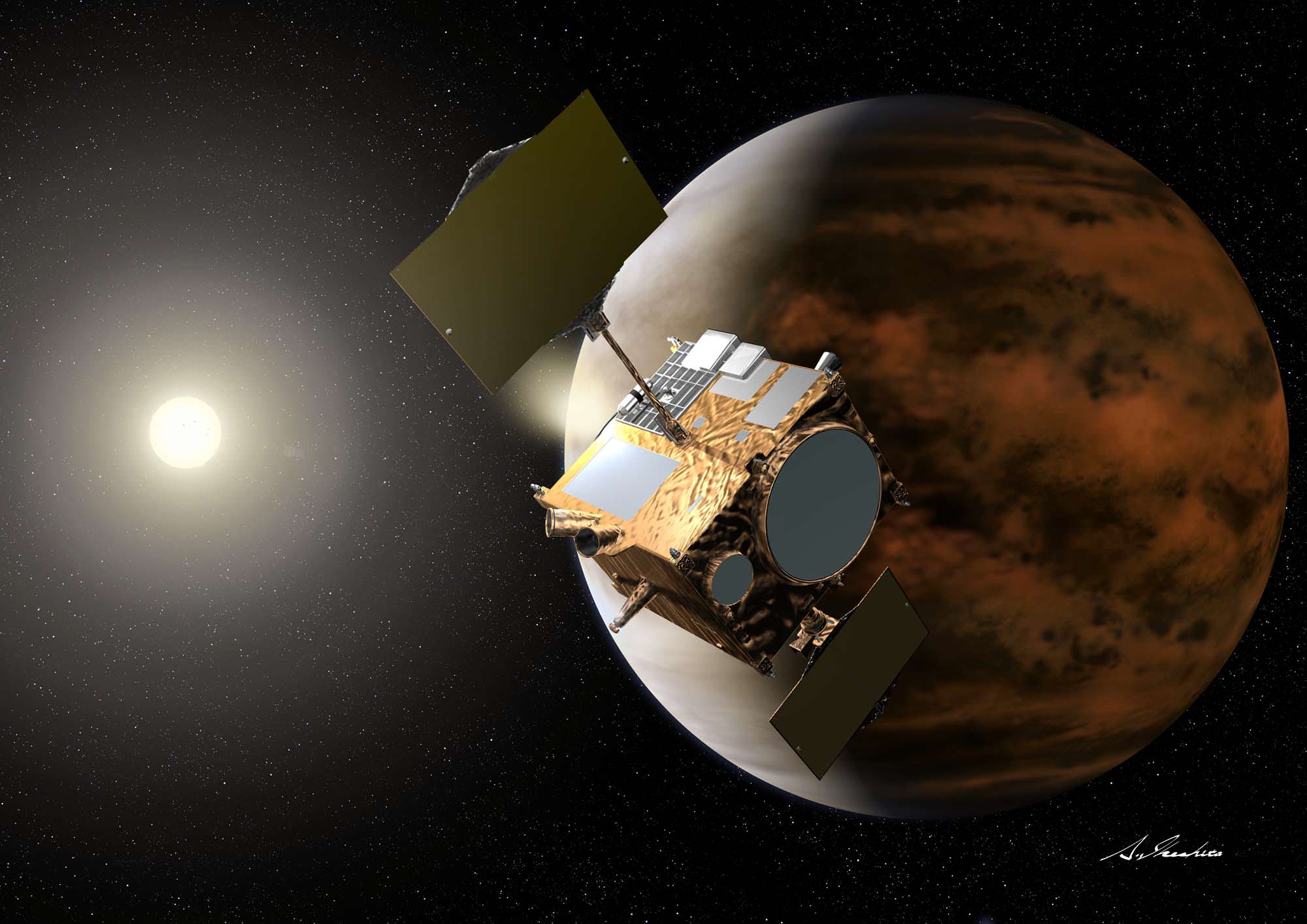

This is an animation of Venus Express performing stellar occultation at Venus. Venus Express is the first mission ever to apply the technique of stellar occultation at Venus. The technique consists of looking at a star through the atmospheric limb. By analysing the way the starlight is absorbed by the atmosphere, one can deduce the characteristics of the atmosphere itself. Credits: ESA (Animation by AOES Medialab)

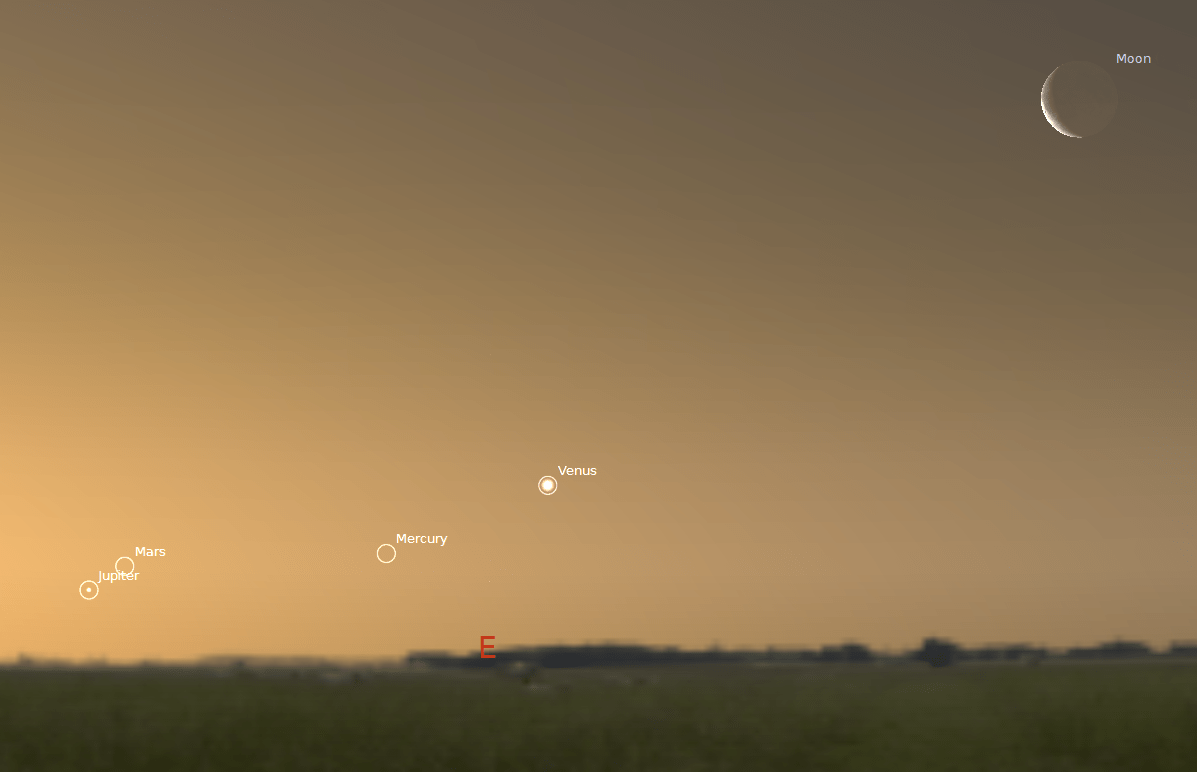

To date, ozone has been the sole property of Earth and Mars – but this type of discovery method could aid astronomers in searching for life on other worlds. Why is it important? Because ozone absorbs most of the Sun’s harmful ultra-violet rays… and because it is believed to be a by-product of life itself. When combined with carbon dioxide, this could create a signature as a strong signal for life. But don’t get too excited at the prospects, yet. The amount of ozone detected is also critical to refining models. It will need to be at least 20% of Earth’s value to even be considered.

“We can use these new observations to test and refine the scenarios for the detection of life on other worlds,” says Dr Montmessin.

While we know that chances are almost non-existent that Venus has life, it still brings it one step closer to planets like Mars and Earth.

“This ozone detection tells us a lot about the circulation and the chemistry of Venus’ atmosphere,” says Hakan Svedhem, ESA Project Scientist for the Venus Express mission. “Beyond that, it is yet more evidence of the fundamental similarity between the rocky planets, and shows the importance of studying Venus to understand them all.”

Original Story Source: ESA Space Science News.