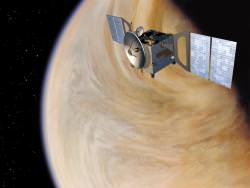

Artist’s view of Venus Express at Venus. Image credit: ESA. Click to enlarge

After a month of maneuvering, ESA’s Venus Express has reached its final science orbit. The spacecraft made its final maneuver on May 6, firings its engines to tighten its orbit to one that ranges between 66,000 and 250 km (41,000 and 155 miles) above the planet. Its scientific instruments will now be turned on and tested over the course of May. This will make the spacecraft ready for its science phase, due to begin on June 4, 2006.

Less than one month after insertion into orbit, and after sixteen loops around the planet Venus, ESA’s Venus Express spacecraft has reached its final operational orbit on 7 May 2006.

Already at 21:49 CEST on 6th May, when the spacecraft communicated to Earth through ESA’s ground station at New Norcia (Australia), the Venus Express ground control team at ESA’s European Spacecraft Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt (Germany) received advanced confirmation that final orbit was to be successfully achieved about 18 hours later.

Launched on 9 November 2005, Venus Express arrived to destination on 11 April 2006, after a five-month interplanetary journey to the inner solar system. The initial orbit – or ‘capture orbit’ – was an ellipse ranging from 330 000 kilometres at its furthest point from Venus surface (apocentre) to less than 400 kilometres at its closest (pericentre).

As of the 9-day capture orbit, Venus Express had to perform a series of further manoeuvres to gradually reduce the apocentre and the pericentre altitudes over the planet. This was achieved by means of the spacecraft main engine – which had to be fired twice during this period (on 20 and 23 April 2006) – and through the banks of Venus Express’ thrusters – ignited five times (on 15, 26 and 30 April, 3 and 6 May 2006).

“Firing at apocentre allows the spacecraft to control the altitude of the next pericentre, while firing at the pericentre controls the altitude of the following apocentre,” says Andrea Accomazzo, Spacecraft Operations Manager at ESOC. “It is through this series of operations that we reached the final orbit last Sunday, about one orbital revolution after the last ‘pericentre change manoeuvre’ on Saturday 6 May”.

Venus Express entered its target orbit at apocentre on 7 May 2006 at 15:31 (CEST), when the spacecraft was at 151 million kilometres from Earth. Now the spacecraft is running on an ellipse substantially closer to the planet than during the initial orbit. The orbit now ranges between 66 000 and 250 kilometres over the Venus and it is polar. The pericentre is located almost above the North pole (80º North latitude), and it takes 24 hours for the spacecraft to travel around the planet.

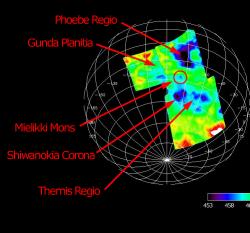

“This is the orbit designed to perform the best possible observations of Venus, given the scientific objectives of the mission. These include global observations of the Venusian atmosphere, of the surface characteristics and of the interaction of the planetary environment with the solar wind,” says Hakan Svedhem, Venus Express Project Scientist. “It allows detailed high resolution observations near pericentre and the North Pole, and it lets us study the very little explored region around the South Pole for long durations at a medium scale,” he concluded.

Until beginning of June, Venus Express will continue its ‘orbit commissioning phase’, started on 22 April this year. “The spacecraft instruments are now being switched on one by one for detailed checking, which we will continue until mid May. Then we will operate them all together or in groups” said Don McCoy, Venus Express Project Manager. “This allows simultaneous observations of phenomena to be tested, to be ready when Venus Express’ nominal science phase begins on 4 June 2006,” he concluded.

Original Source: ESA Portal