Monday, July 16 – Today in 1850 at Harvard University, the first photograph of a star (other than the Sun) was made. The honors went to Vega! In 1994, an impact event was about to happen as nearly two dozen fragments of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 were speeding their way to the surface of Jupiter. The result was spectacular, and the visible features left behind on the planet’s atmosphere were the finest ever recorded. Why not take the time to look at Jupiter again tonight while it still holds good sky position? No matter where you observe from, this constantly changing planet offers a wealth of things to look at – be it the appearance of the Great Red Spot, or just the ever changing waltz of the Galilean moons. Tonight the Moon and Saturn will not only be close – but very close! Be sure to check IOTA information for a visible occultation event!

Now let’s return again to the oblate and beautiful M19 and drop two fingerwidths south for another misshapen globular – M62.

At magnitude 6, this 22,500 light-year distant Class IV cluster can be spotted in binoculars, but comes to wonderful life in the telescope. First discovered by Messier in 1771, Herschel was the first to resolve it and report on its deformation. Because it is so near to the galactic center, tidal forces have “crushed” it – much like M19. You will note when studying in the telescope that its core is very off center. Unlike M19, M62 has at least 89 known variable stars – 85 more than its neighbor – and the dense core may have undergone collapse. A large number of X-ray binaries have also been discovered within its structure, perhaps caused by the close proximity of stellar members. Enjoy it tonight!

Tuesday, July 17 – Tonight the Moon has returned in a position to favor a bit of study. Start by checking IOTA information for a possible visible occultation of Regulus, and look for Saturn quite nearby as the slender crescent graces the early evening skies.

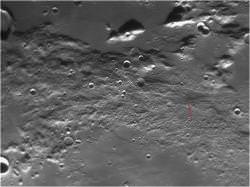

Although poor position makes study difficult during the first few lunar days, be sure to look for the ancient impact Vendelinus just slightly south of central. Spanning approximately 150 kilometers in diameter and with walls reaching up to 4400 meters in height, lava flow has long ago eradicated any interior features. Its old walls hold mute testimony to later impact events as you view crater Holden on the south shore and much larger Lame on the northeast edge and sharp Lohse northwest. Mark your challenge list!

If you’re up to another challenge tonight, let’s go hunting Herschel I.44, also known as NGC 6104. You’ll find this 9.5 magnitude globular cluster around two fingerwidths northeast of Theta Ophiuchi and a little more than a degree due east of star 51 (RA 17 38 36.93 Dec -23 54 31.5).

Discovered by William Herschel in 1784 and often classed as “uncertain,” today’s powerful telescopes have placed this halo object as a Class VIII and given it a rough distance from the galactic center of 8,800 light-years. Although neither William nor John could resolve this globular, and they listed it originally as a bright nebula, studies in 1977 revealed a nearby suspected planetary nebula named Peterson 1. Thirteen years later, further study revealed this to be a symbiotic star.

Symbiotic stars are a true rarity – not a singular star at all, but a binary system. A red giant dumps mass towards a white dwarf in the form of an accretion disc. When this reaches critical mass, it then causes a thermonuclear explosion resulting in a planetary nebula. While no evidence exists that this phenomenon is physically located within metal-rich NGC 6401, just being able to see it in the same field makes this journey both unique and exciting!

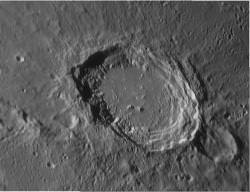

Wednesday, July 18 – On this day 27 years ago, India launched its first satellite (Rohini 1), and 31 years ago in the United States Gemini 10 launched carrying John Young and Michael Collins to space. Tonight we’ll launch our imaginations as we view the area around Mare Crisium and have a look at this month’s lunar challenge – Macrobius. You’ll find it just northwest of the Crisium shore…

Spanning 64 kilometers in diameter, this Class I impact crater drops to a depth of nearly 3600 meters – about the same as many of our earthly mines. Its central peak rises up 1100 meters, and may be visible as a small speck inside the crater’s interior. Be sure to mark your lunar challenges and look for other features you may have missed before!

Since the moonlight will now begin to interfere with our globular cluster studies, let’s waive them for a while as we take a look at some of the region’s most beautiful stars. Tonight your goal is to locate Omicron Ophiuchi, about a fingerwidth northeast of Theta. At a distance of 360 light-years, this system is easily split by even small telescopes. The primary star is slightly dimmer than magnitude 5 and appears yellow to the eye. The secondary is near 7th magnitude and tends to be more orange in color. This wonderful star is part of many double star observing lists, so be sure to note it!

Thursday, July 19 – Today in 1846, Edward Pickering was born. Although his name is not well known, he became a pioneer in the field of spectroscopy. Pickering was the Harvard College Observatory Director from 1876 to 1919, and it was during his time there that photography and astronomy began to merge. Known as the Harvard Plate Collection, these archived beginnings still remain a valuable source of data.

With plenty of Moon to explore tonight, why don’t we try locating an area where many lunar exploration missions made their mark? Binoculars will easily reveal the fully disclosed areas of Mare Serenitatis and Mare Tranquillitatis, and it is where these two vast lava plains converge that we will set our sights. Telescopically, you will see a bright “peninsula” westward of where the two conjoin which extends toward the east. Just off that look for bright and small crater Pliny. It is near this rather inconspicuous feature that the remains Ranger 6 lie forever preserved where it crashed on February 2, 1964.

Unfortunately, technical errors occurred and it was never able to transmit lunar pictures. Not so Ranger 8! On a very successful mission to the same relative area, this time we received 7137 “postcards from the Moon” in the last 23 minutes before hard landing. On the “softer” side, Surveyor 5 also touched down near this area safely after two days of malfunctions on September 10, 1967. Incredibly enough, the tiny Surveyor 5 endured temperatures of up to 283 degrees F, but was able to spectrographically analyze the area’s soil… And by the way, it also managed to televise an incredible 18,006 frames of “home movies” from its distant lunar locale.

When you’re finished, why not have a look at something that would make Edward Pickering proud? He enthusiastically encouraged amateur astronomers, and founded the American Association of Variable Star Observers – so set your sights on RR Scorpius about two fingerwidths northeast of Eta and less than a fingerwidth southwest M62 (RA 16 56 37.84 Dec -30 34 48.2). This very red Mira type can reach as high as magnitude 5 and drop as low as 12 in about 280 days!

Friday, July 20 – Today was a busy day in astronomy history! In 1969, the world held its breath as the Apollo 11 lander touched down and Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin became the first humans to touch the lunar surface. We celebrate our very humanity because even Armstrong was so moved that he messed up his lines! The famous words were meant to be “A small step for a man. A giant leap for mankind.” That’s nothing more than one small error for a man, and mankind’s success continued on July 20, 1976 when Viking 1 landed on Mars – sending back the first images ever taken from that planet’s surface.

Tonight let’s celebrate 36 years of space exploration and walk on the Moon where the first man set foot. For SkyWatchers, the dark round area you see on the northeastern limb is Mare Crisium and the dark area below that is Mare Fecunditatis. Now look mid-way on the terminator for the dark area that is Mare Tranquillitatis. At its southwest edge, history was made.

In binoculars, trace along the terminator where the Caucasus Mountains stand – and then south for the Apennines and the Haemus Mountains. As you continue towards the center of the Moon, you will see where the shore of Mare Serenitatis curves east, and also the bright ring of Pliny. Continue south along the terminator until you spot the small, bright ring of Dionysius along the edge of Mare Tranquillitatis. Just to the southwest, you may be able to see the soft rings of Sabine and Ritter. It is near here where the base section of the Apollo 11 landing module – Eagle – lies forever enshrined in “magnificent desolation.”

For telescope users, the time is now to power up! See if you can spot small craters Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins just east. Even if you cannot, the Apollo 11 landing area is about the same distance as Sabine and Ritter are wide to the east-southeast.

Even if you don’t have the opportunity to see it tonight, take the time during the next couple of days to point it out to your children, grandchildren, or even just a friend… The Moon is a spectacular world and we’ve been there!

Saturday, July 21 – Today in 1961, Mercury 4 was launched, sending Gus Grissom into suborbital space on the second manned flight, and he returned safely in Liberty Bell 7.

Long before the Sun sets, look for the Moon to appear in the still-blue sky. As it darkens, watch for brilliant blue/white Spica to be around a fingerwidth north of the Moon. Have you ever wondered if there was any place on the lunar surface that hasn’t seen the sunlight? Then let’s go searching for one tonight…

Our first order of business will be to identify crater Albategnius. Directly in the center of the Moon is a dark floored area known as Sinus Medii. South of it will be two conspicuously large craters – Hipparchus to the north and ancient Albategnius to the south. Trace along the terminator toward the south until you have almost reached its point (cusp) and you will see a black oval. This normal looking crater with the brilliant west wall is equally ancient crater Curtius. Because of its high southern latitude, we shall never see the interior of this crater – and neither has the Sun! It is believed that the inner walls are quite steep and that Curtius’ interior has never been illuminated since its formation billions of years ago. Because it has remained dark, we can speculate that there may be “lunar ice” pocketed inside its many cracks and rilles that date back to the Moon’s formation!

Because our Moon has no atmosphere, the entire surface is exposed to the vacuum of space. When sunlit, the surface reaches up to 385 K, so any exposed “ice” would vaporize and be lost because the Moon’s gravity cannot hold it. The only way for “ice” to exist would be in a permanently shadowed area. Near Curtius is the Moon’s south pole, and the Clementine spacecraft’s imaging showed around 15,000 square kilometers in which such conditions could exist. So where did this “ice” come from? The lunar surface never ceases to be pelted by meteorites – most of which contain water ice. As we know, many craters were formed by just such impacts. Once hidden from the sunlight, this “ice” could remain for millions of years!

Sunday, July 22 – Tonight instead of lunar exploration, we will note the work of Friedrich Bessel, who was born on this day in 1784. Bessel was a German astronomer and mathematician whose functions, used in many areas of mathematical physics, still carry his name. But, you may put away your calculator, because Bessel was also the very first person to measure a star’s parallax. In 1837, he chose 61 Cygni and the result was no more than a third of an arc second. His work ended a debate that had stretched back two millennia to Aristotle’s time and the Greek’s theories about the distances to the stars.

Although you’ll need to use your finderscope with tonight’s bright skies, you’ll easily locate 61 between Deneb (Alpha) and Zeta on the eastern side. Look for a small trio of stars and choose the westernmost. Not only is it famous because of Bessel’s work, but it is one of the most noteworthy of double stars for a small telescope. 61 Cygni is the fourth nearest star to Earth, with only Alpha Centauri, Sirius, and Epsilon Eridani closer. Just how close is it? Try right around 11 light-years.

Visually, the two components have a slightly orange tint, are less than a magnitude apart in brightness and have a nice separation of around 30″ to the south-southeast. Back in 1792, Piazzi first noticed 61’s abnormally large proper motion and dubbed it “The Flying Star.” At that time, it was only separated by around 10″ and the B star was to the northeast. It takes nearly 7 centuries for the pair to orbit each other, but there is another curiosity here. Orbiting the A star around every 4.8 years is an unseen body that is believed to be about 8 times larger than Jupiter. A star – or a planet? With a mass considerably smaller than any known star, chances are good that when you view 61 Cygni, you’re looking toward a distant world!