[/caption]

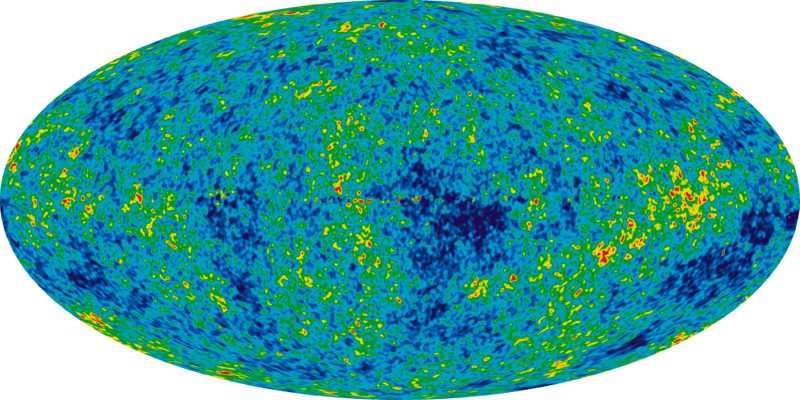

Not since the work of Fritz Zwicky has the astronomy world been so excited about the missing mass of the Universe. His evidence came from the orbital velocities of galaxies in clusters, rotational speeds, and gravitational lensing of background objects. Now there’s even more evidence that Zwicky was right as Australian student – Amelia Fraser-McKelvie – made another breakthrough in the world of astrophysics.

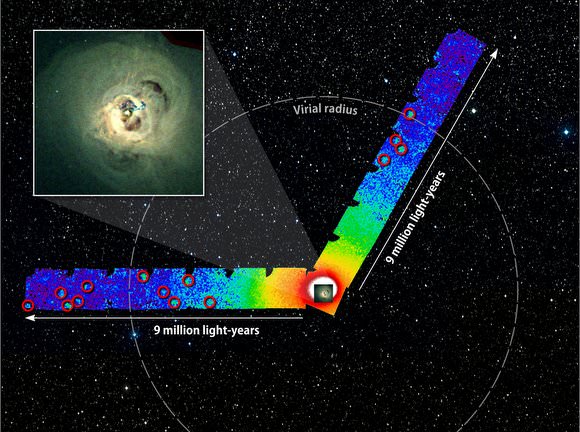

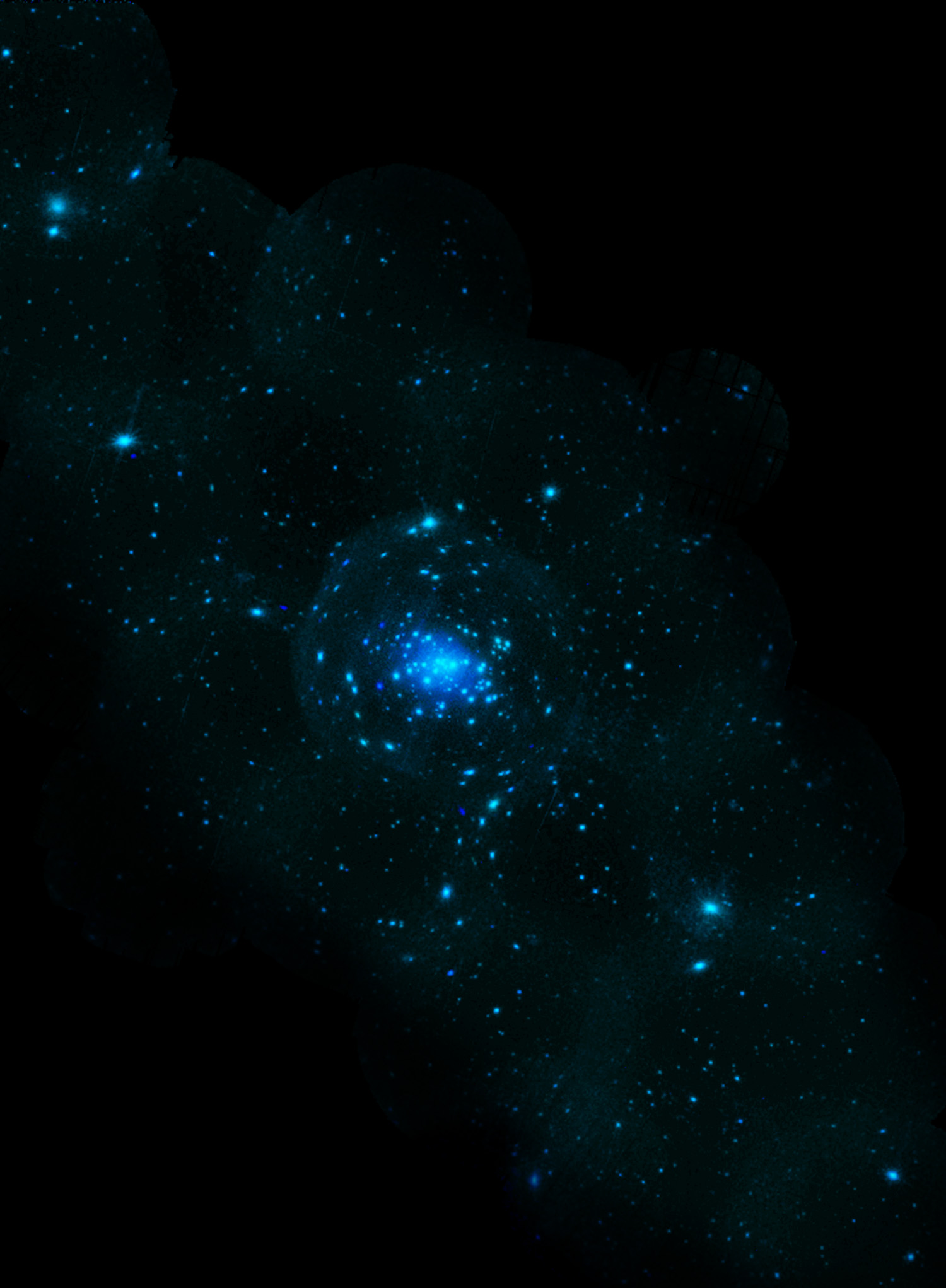

Working with a team at the Monash School of Physics, the 22-year-old undergraduate Aerospace Engineering/Science student conducted a targeted X-ray search for the hidden matter and within just three months made a very exciting discovery. Astrophysicists predicted the mass would be low in density, but high in temperature – approximately one million degrees Celsius. According to theory, the matter should have been observable at X-ray wavelengths and Amelia Fraser-McKelvie’s discovery has proved the prediction to be correct.

Dr Kevin Pimbblet from the School of Astrophysics explains: “It was thought from a theoretical viewpoint that there should be about double the amount of matter in the local Universe compared to what was observed. It was predicted that the majority of this missing mass should be located in large-scale cosmic structures called filaments – a bit like thick shoelaces.”

Up until this point in time, theories were based solely on numerical models, so Fraser-McKelvie’s observations represent a true break-through in determining just how much of this mass is caught in filamentary structure. “Most of the baryons in the Universe are thought to be contained within filaments of galaxies, but as yet, no single study has published the observed properties of a large sample of known filaments to determine typical physical characteristics such as temperature and electron density.” says Amelia. “We examine if a filament’s membership to a supercluster leads to an enhanced electron density as reported by Kull & Bohringer (1999). We suggest it remains unclear if supercluster membership causes such an enhancement.”

Still a year away from undertaking her Honors year (which she will complete under the supervision of Dr Pimbblet), Ms Fraser-McKelvie is being hailed as one of Australia’s most exciting young students… and we can see why!