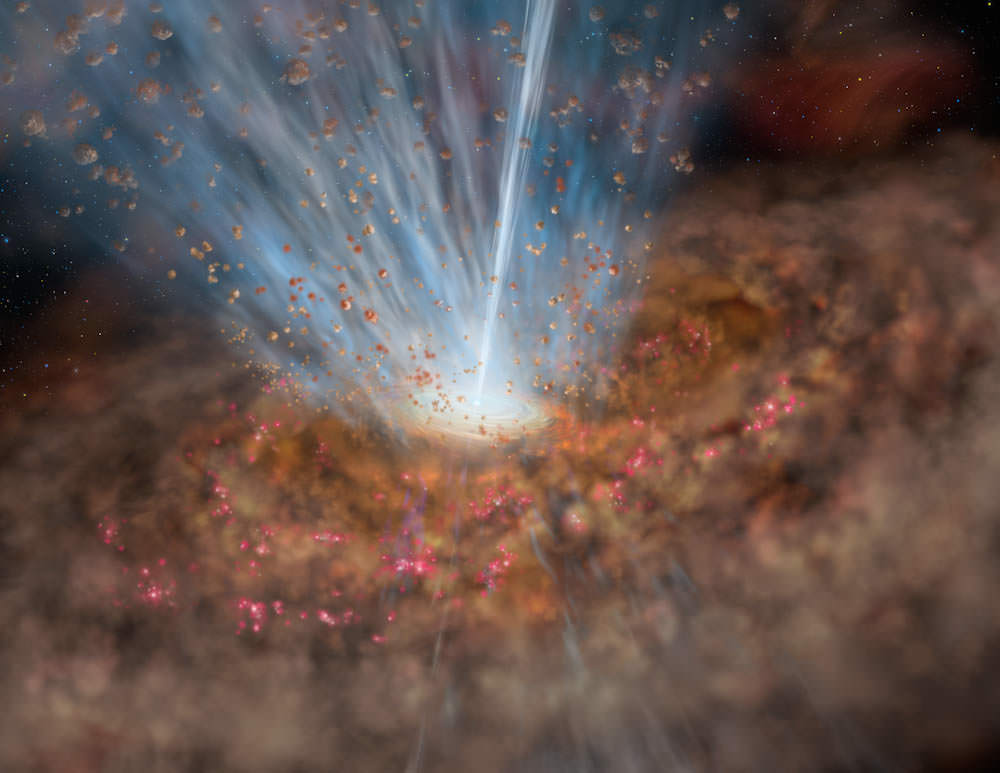

This week, astronomers announced the detection of a rare event, a star being torn to shreds by a massive black hole in the heart of a distant dwarf galaxy. The evidence was presented Wednesday January 8th at the ongoing 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society being held this week in Washington D.C.

Although other instances of the death of stars at the hands of black holes have been witnessed before, Chandra may have been the first to document an intermediate black hole at the heart of a dwarf galaxy “in the act”.

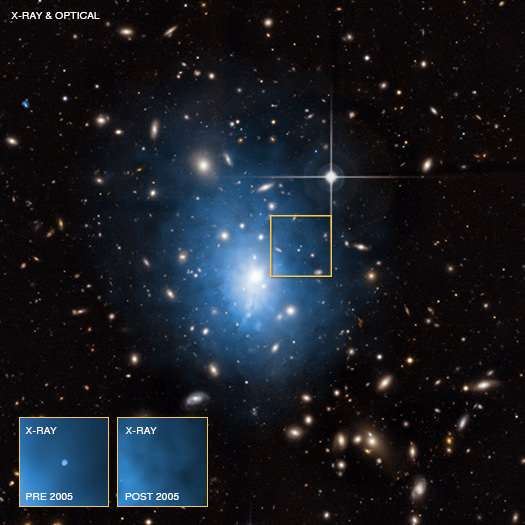

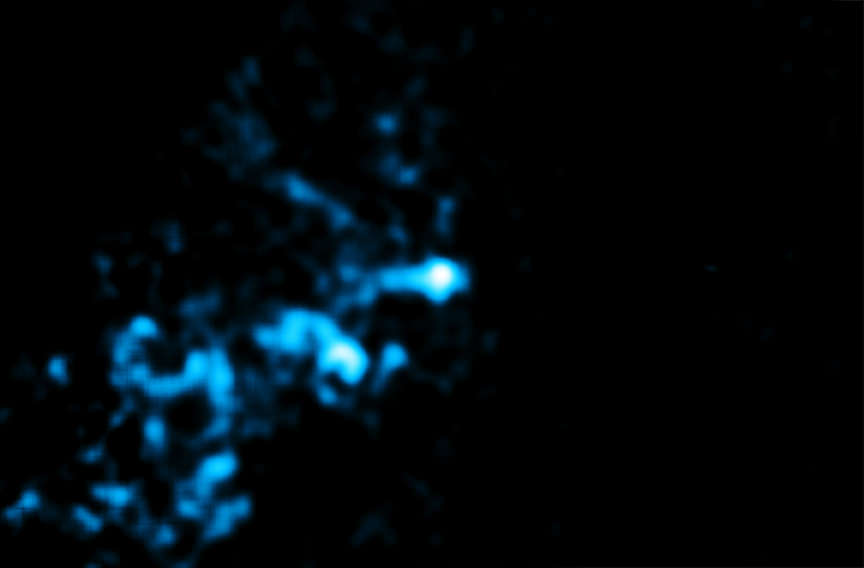

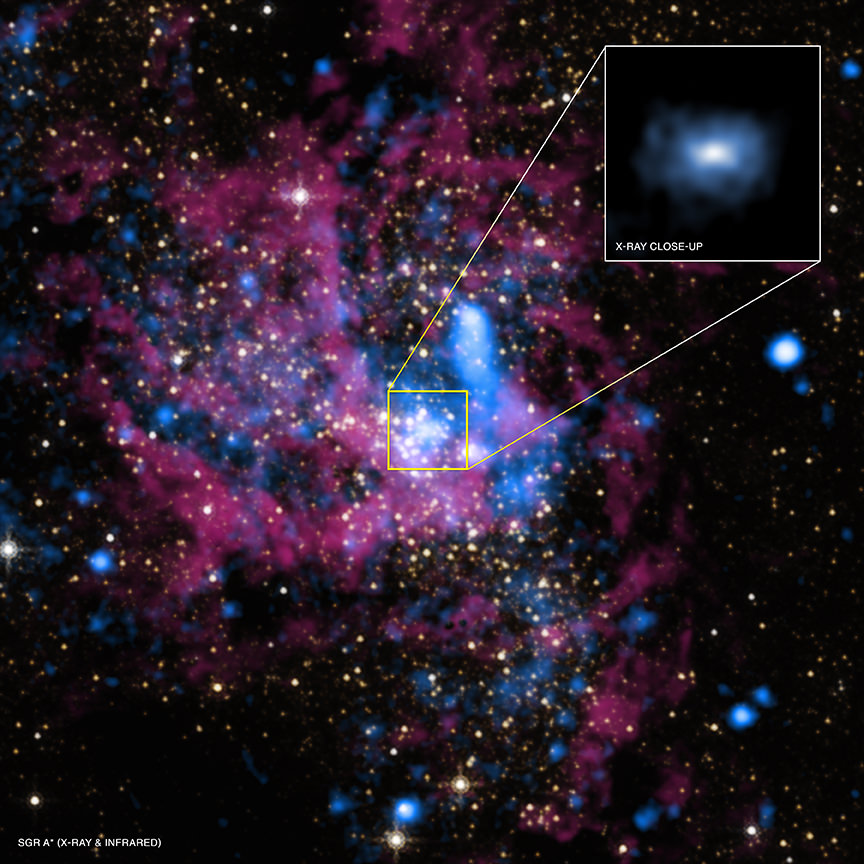

The results span observations carried out by the space-based Chandra X-ray observatory over a period spanning 1999 to 2005. The search is part of an archival study of observations, and revealed no further outbursts after 2005.

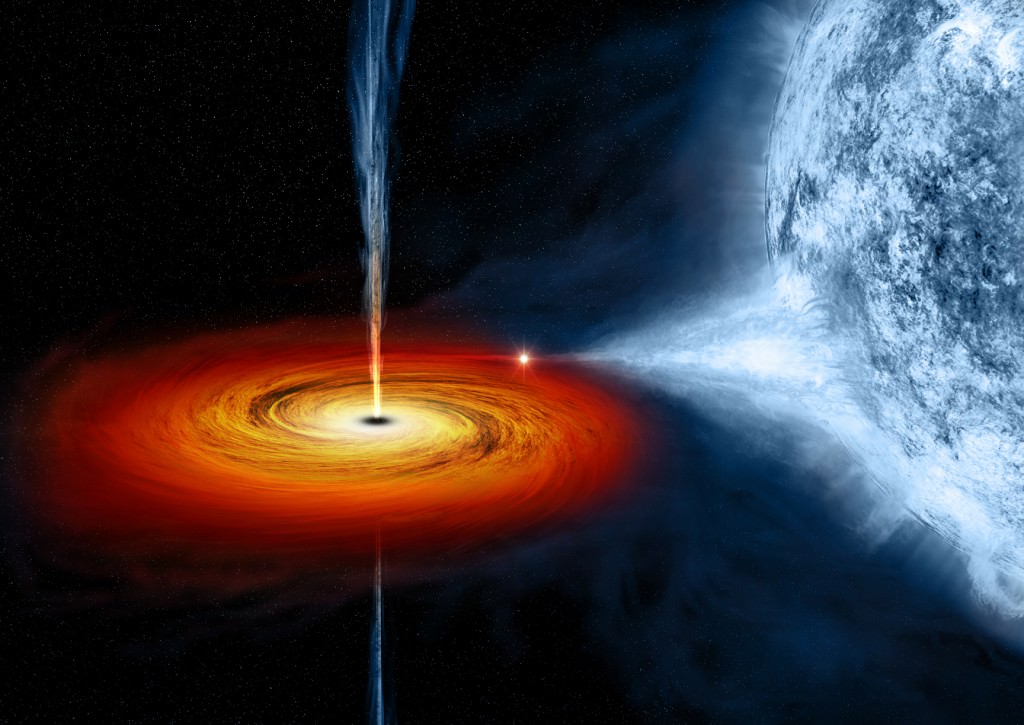

“We can’t see the star being torn apart by the black hole, but we can track what happens to the star’s remains,” said University of Alabama’s Peter Maksym in a recent press release. A comparison of with similar events seen in larger galaxies backs up the ruling of “death by black hole.” A competing team led by Davide Donato also looked at archival data from Chandra and the Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer (EUVE), along with supplementary observations from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope to determine the brightness of the host galaxy, and gained similar results.

The dwarf galaxy in the Abell 1795 cluster that was observed has the name WINGS J134849.88+263557.5, or WINGS J1348 for short. The Abell 1795 cluster is about 800 million light years distant.

WINGS denotes the galaxy’s membership in the WIde-field Nearby Galaxy-cluster Survey, and the phone number-like designation is the galaxy’s position in the sky in right ascension and declination.

Like most galaxies associated with galaxy clusters, WINGS J1348 a dwarf galaxy probably smaller than our own satellite galaxy known as the Large Magellanic Cloud. The Abell 1795 cluster is located in the constellation Boötes, and WINGS J1348 has an extremely faint visual magnitude of +22.46.

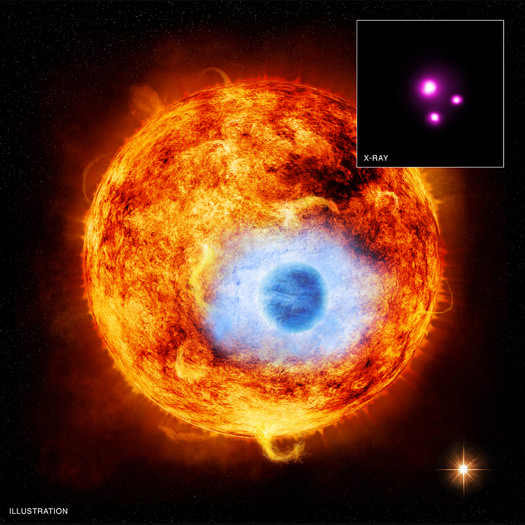

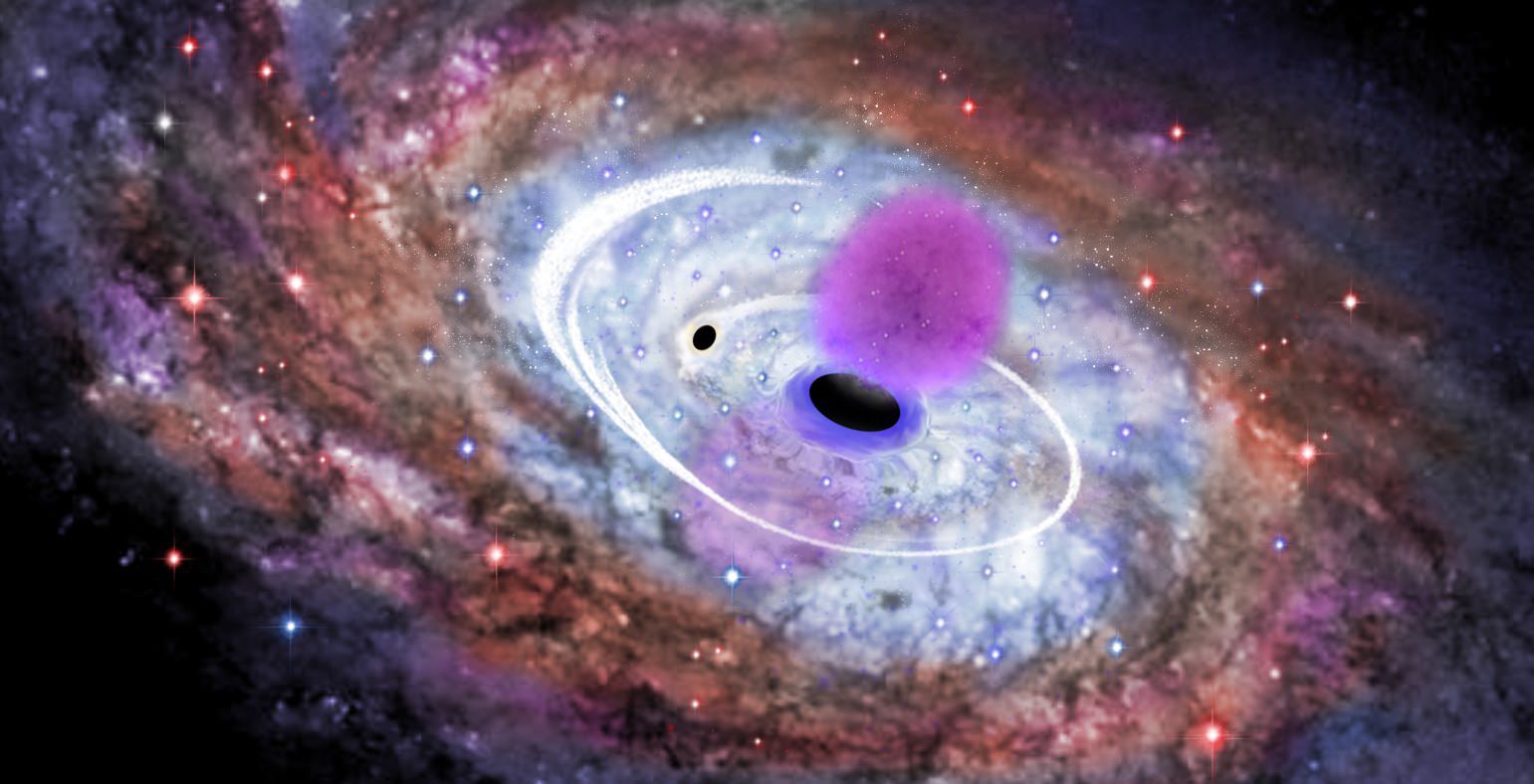

“Scientists have been searching for these intermediate mass black holes for decades,” NASA’s Davide Donato said in a recent press release “We have lots of evidence for small black holes and very big ones, but these medium-sized ones have been tough to pin down.”

Maksym notes in an interview with Universe Today that this isn’t the first detection of an intermediate-mass black hole, which are a class of black holes often dubbed the “mostly” missing link between stellar mass and super massive black holes.

The mass range for intermediate black holes is generally pegged at 100 to one million solar masses.

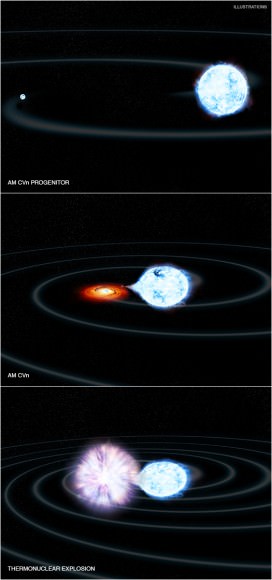

What makes the event witnessed by Chandra in WINGS J1348 special is that astronomers managed to capture a rare tidal flare, as opposed to a supermassive black hole in the core of an active galaxy.

“Most of the time, black holes eat very little, so they can hide very well,” Maksym said in the AAS meeting on Wednesday.

This discovery pushes the limits on what we know of intermediate black holes. By documenting an observed number of tidal flare events, it can be inferred that a number of inactive black holes must be lurking in galaxies as well. The predicted number of tidal events that occur also have implications for the eventual detection of gravity waves from said mergers.

And more examples of these types of X-ray flare events could be waiting to be uncovered in the Chandra data as well.

“Chandra has taken quite a few pictures over the past 13+ years, and collaborators and I have an ongoing program to look for more tidal flares,” Maksym told Universe Today. “We’ve found one other this way, from a larger galaxy, and hope to find more. Abell 1795 was a particularly good place to look because as a calibration source, there were tons of pictures.”

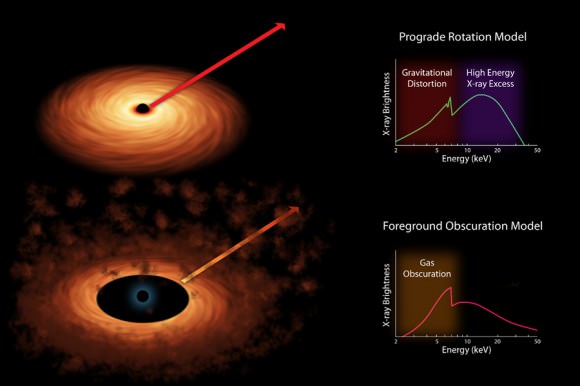

Use of Chandra data was also ideal for the study because its spatial resolution allowed researchers to pinpoint an individual galaxy in the cluster. Maksym also notes that while it’s hard to get follow-up observations of events based on archival data, future missions dedicated to X-ray astronomy with wider fields of view may be able to scour the skies looking for such tidal flaring events.

The NuSTAR satellite was the latest X-Ray observatory to launch in 2012. NASA’s Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer picked up a strong ultraviolet source in 1998 right around the time of the tidal flare event, and ESA’s XMM-Newton satellite may have detected the event in 2000 as well.

This was also one of the smallest galaxies ever observed to contain a black hole. Maksym noted in Wednesday’s press conference that an alternative explanation could be a super-massive black hole in a tiny galaxy that just “nibbled” on a passing star, but said that new data from the Gemini observatory does not support this.

“It would be like looking into a dog house and finding a large ogre crammed in there,” Maksym said at Wednesday’s press conference.

This discovery provides valuable insight into the nature of intermediate mass black holes and their formation and behavior. What other elusive cosmological beasties are lying in wait to be discovered in the archives?

Congrats to Maksym and teams on this exciting new discovery, and the witnessing of a rare celestial event!