[/caption]

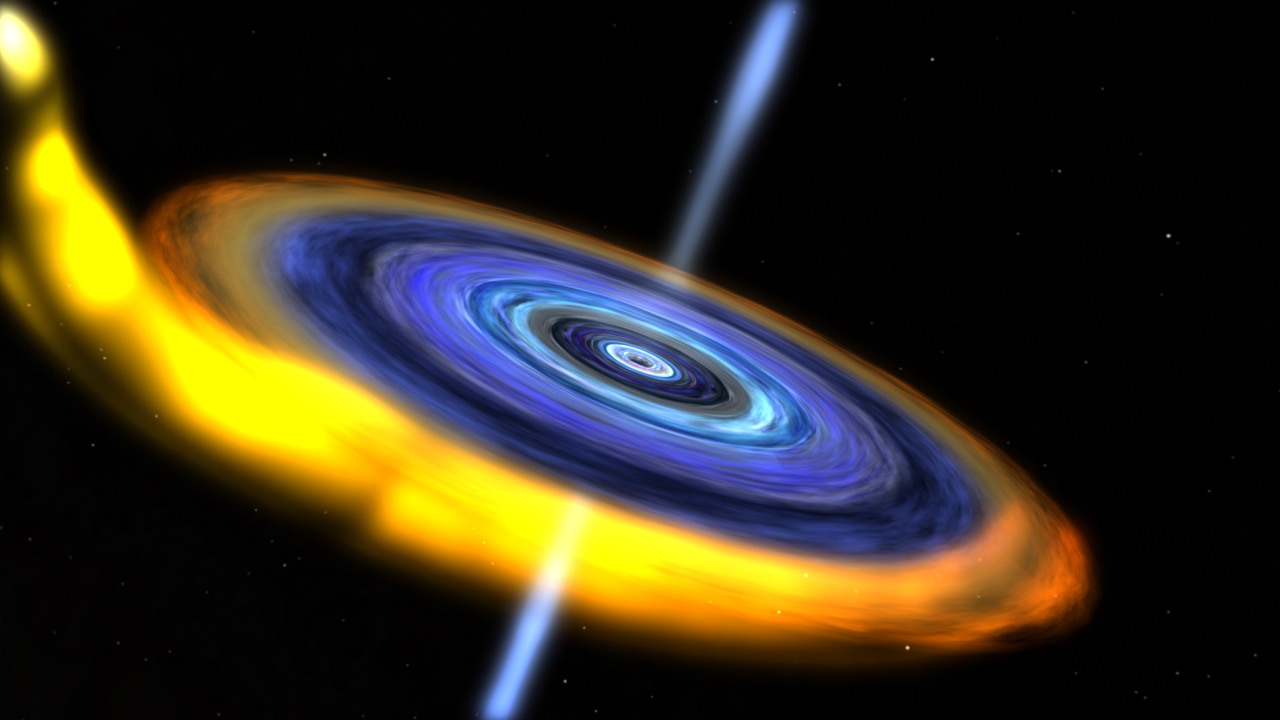

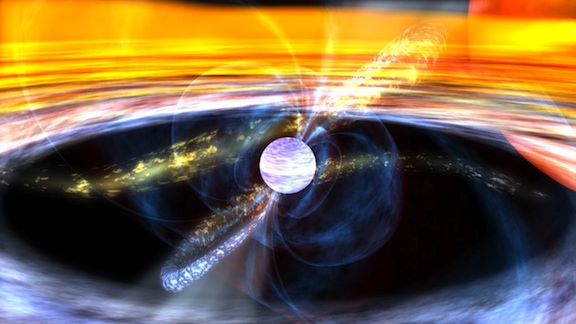

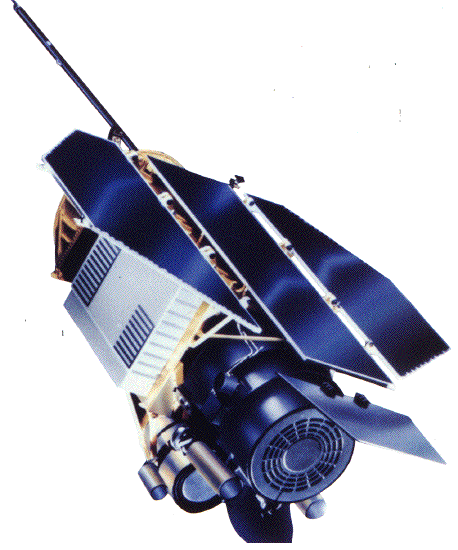

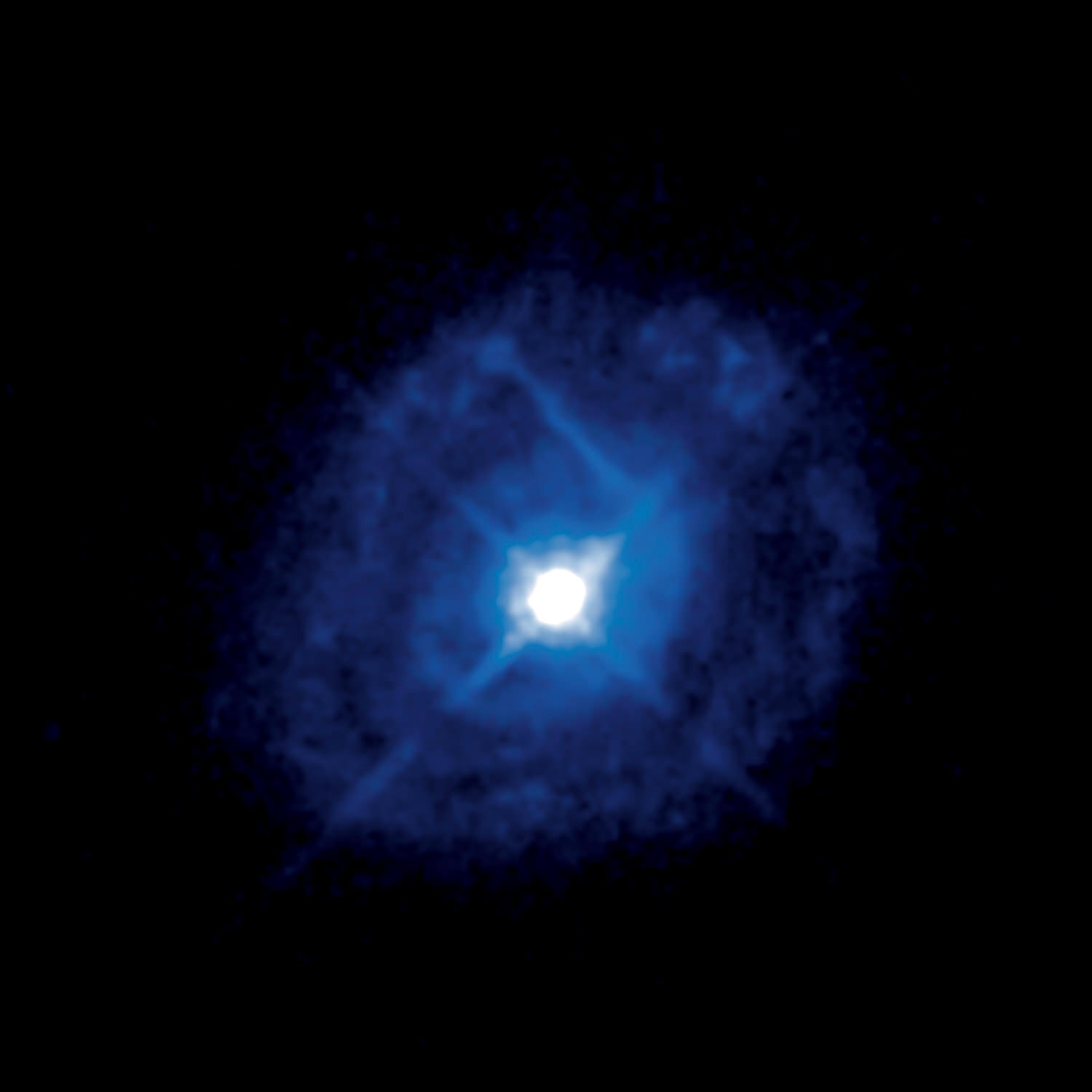

For more than 16 years, 2,200 papers in refereed journals, 92 doctoral theses, and more than 1,000 rapid notifications alerting astronomers around the globe to new astronomical activity, the NASA Rossi X-Ray Timing Explorer is now retired. It sent the last of its data on January 4th of this year and on January 5th the plucky little satellite was decommissioned. If you’re not familiar with Rossi’s activities, then picture sending back images and data on the extreme environments around white dwarfs, neutron stars and black holes… because that’s what made the mission famous.

On December 30, 1995, the mission was launched as XTE from Cape Canaveral, Florida on board a Delta II 7920 rocket. Within weeks it was named in honor of Bruno Rossi, an MIT astronomer and a pioneer of X-ray astronomy and space plasma physics who died in 1993. However, the mission itself didn’t die – it excelled with honors. The entire scientific community recognized the importance of RXTE research and bestowed it with five awards – four Rossi Prizes (1999, 2003, 2006 and 2009) from the High Energy Astrophysics Division of the AAS and the 2004 NWO Spinoza prize, the highest Dutch science award, from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

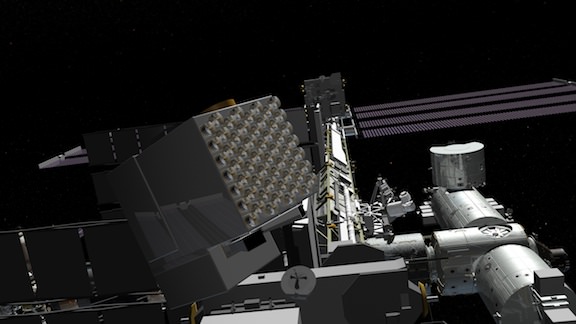

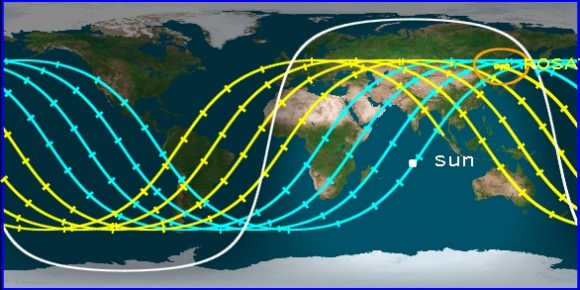

On board, the Rossi was three scientific instruments housed in one unit. The first was the Proportional Counter Array (PCA), which was centered on the lower end of the energy band and was crafted by Goddard. The second instrument was the High Energy X-Ray Timing Experiment (HEXTE) that could be aimed at very specific targets and was manufactured by the University of California at San Diego for exploring the upper energy range. The last of the trio was the All-Sky Monitor developed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge. It took in about 80% of the sky during each orbit, delivering astronomers with an unprecedented amount of data on the wide variances of X-Ray sky and allowing them to record bright sources over a period of time as short as a few microseconds up to months. All of this information was taken in over a broad span of energy ranging from 2,000 to 250,000 electron volts.

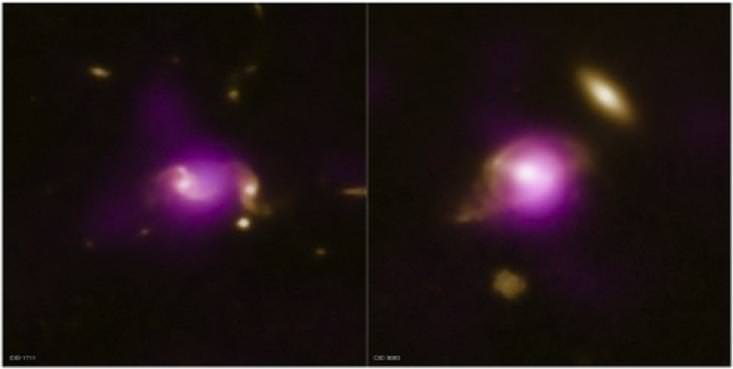

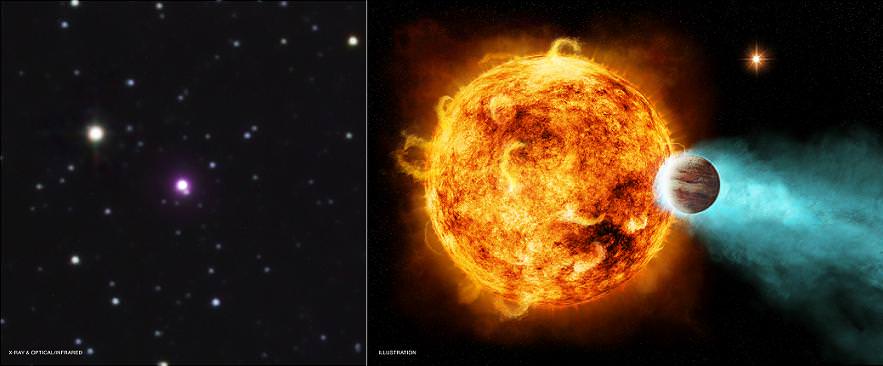

The Rossi X-Ray Timing Explorer asked little and returned much. Over its operating lifetime it gave us new insight in the life cycles of neutron stars and black holes. Through its eyes we learned about magnetars and discovered the first accreting millisecond pulsar. But that’s not all. The RXTE provided hard evidence which supported Einstein’s theory by observing “frame dragging” in the neighborhood of a black hole. Even though the instrumentation would be considered antique by today’s standards, it certainly served its purpose. “The spacecraft and its instruments had been showing their age, and in the end RXTE had accomplished everything we put it up there to do, and much more,” said Tod Strohmayer, RXTE project scientist at Goddard.

According to the NASA news release, the decision to decommission RXTE followed the recommendations of a 2010 review board tasked to evaluate and rank each of NASA’s operating astrophysics missions. The three and a half ton satellite is expected to return to Earth sometime between the years 2014 and 2023, depending on solar activity. It will have a fiery end… burning out like the superstar that it was. To celebrate its career, the scientific community will hold a special session on RXTE during the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Austin, Texas. The session is scheduled for Tuesday, January 10, at 3 p.m. CST. A press conference on new RXTE results will also be held at the meeting on January 10 at 1:45 p.m. EST. The decision to decommission RXTE followed the recommendations of a 2010 review board tasked to evaluate and rank each of NASA’s operating astrophysics missions. “After two days we listened to verify that none of the systems we turned off had autonomously re-activated, and we’ve heard nothing,” said Deborah Knapp, RXTE mission director at Goddard.

On the contrary… We heard a lot from Rossi!

Original Story Source: NASA News Release.