To celebrate the 45th anniversary of the Apollo 13 mission, Universe Today is featuring “13 MORE Things That Saved Apollo 13,” discussing different turning points of the mission with NASA engineer Jerry Woodfill.

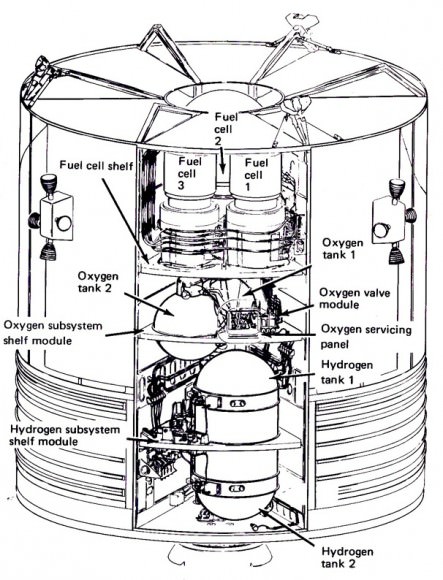

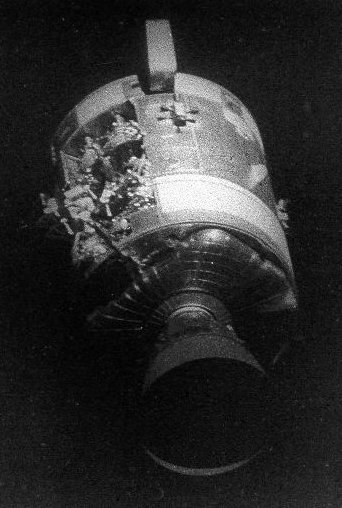

Understandably, it was chaotic in both Mission Control and in the spacecraft immediately after the oxygen tank exploded in Apollo 13’s Service Module on April 13, 1970.

No one knew what had happened.

“The Apollo 13 failure had occurred so suddenly, so completely with little warning, and affected so many spacecraft systems, that I was overwhelmed,” wrote Sy Liebergot in his book, Apollo EECOM: Journey of a Lifetime. “As I looked at my data and listened to the voice report, nothing seemed to make sense.”

But somehow, within 53 minutes of the explosion, the ship was stabilized and an emergency plan began to evolve.

“Of all of the things that rank at the top of how we got the crew home,” said astronaut Ken Mattingly, who was sidelined from the mission because he might have the measles, “was sound management and leadership.”

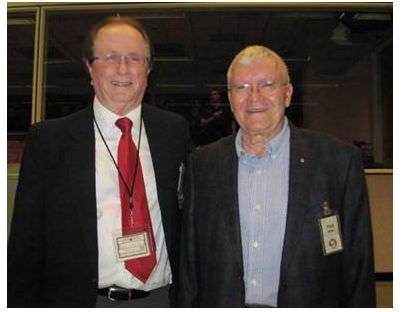

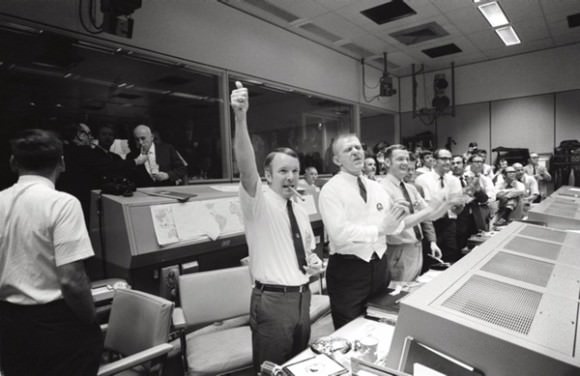

By chance, at the time of the explosion, two Flight Directors — Gene Kranz and Glynn Lunney — were present in Mission Control. NASA engineer Jerry Woodfill feels having these two experienced veterans together at the helm at that critical moment was one of the things that helped save the Apollo 13 crew.

“The scenario resulted from the timing,” Woodfill told Universe Today, “with the explosion occurring at 9:08 PM, and Kranz as Flight Director, but with Lunney present to assume the “hand-off” around 10:00 PM. That assured that the expertise of years of flight control leadership was conferring and assessing the situation. The presence of these colleagues, simultaneously, had to be one of the additional thirteen things that saved Apollo 13. With Lunney looking on, the transition was as seamless as a co-pilot taking the helm from a pilot of a 747 passenger jet.”

Woodfill made an additional comparison: “Having the two Flight Directors on hand at that critical moment is like having Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson on a six-man basketball squad and the referee ignoring any fouls their team might make.”

Lunney described the time of the explosion in an oral history project at Johnson Space Center:

“Gene was on the team before me and he had had a long day in terms of hours. …And shortly before his shift was scheduled to end is when the “Houston, we’ve got a problem” report came in. And at first, it was not terribly clear how bad this problem was. And one of the lessons that we had learned was, “Don’t go solving something that you don’t know exists.” You’ve got to be sure … So, it was generally a go slow, let’s not jump to a conclusion, and get going down the wrong path…. We had a number of situations to deal with.”

The “not jumping to conclusions” was equally expressed by Kranz when he told his team, “Let’s solve the problem, but let’s not make it any worse by guessing.”

The presence of Kranz and Lunney, simultaneously, is especially obvious reading Gene Kranz’s book, Failure Is Not an Option.

“Kranz captures the wealth of “brain power” present at the moment of the explosion,” said Woodfill. “Besides both Kranz and Lunney, their entire teams overlapped. Yes, there were two squads on the floor competing with the dire opponents who threatened the crew’s survival.”

The crew’s survival was foremost in the minds of the Flight Directors. “We will never surrender, we will never give up a crew,” Kranz said later.

Perhaps, the most obvious evidence of how fortuitous the presence of both Kranz and Lunney was, Kranz recorded on page 316-317 of his book. The pair refuses to accept the more popular but potentially fatal decision (a direct abort) to speed the crew’s return to Earth using the damaged command ship’s engine. The direct abort would have been to jettison the lander and fire the compromised command ship’s engine to potentially quicken the return to Earth by 50 hours.

Mattingly recalled those early minutes in Mission Control after the explosion.

“The philosophy was ‘never get in the way of success,’” said Mattingly, speaking at a 2010 event at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. “We had choices, we debated about turning immediately around and coming home or going around the moon. In listening to all of those discussions, we never closed the door about any option of getting home. We didn’t know yet how we were going to get there, but you always make sure you don’t take a step that would jeopardize it.”

And so, with the help of their teams, the two Flight Directors quickly ran through all the options, the pros and cons, and – again – within 53 minutes after the accident they made the decision to have the crew continue their trajectory around the Moon.

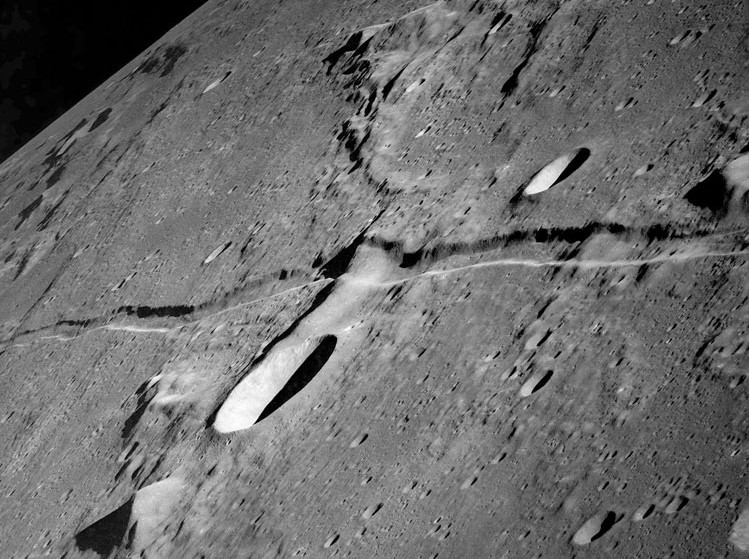

Later, when Jim Lovell commented on viewing the damaged Service Module when it was jettisoned before the crew re-entered Earth’s atmosphere — “There’s one whole side of that spacecraft missing. Right by the high gain antenna, the whole panel is blown out, almost from the base to the engine,” — it was indeed an ominous look at what might have ensued using it for a quick return to Earth.

By the end of the Lunney team’s shift about ten hours after the explosion, Mission Control had put the vehicle back on an Earth return trajectory, the inertial guidance platform had been transferred to the Lunar Module, and the Lunar Module was stable and powered up for the burn planned the would occur after the crew went around the Moon. “We had a plan for what that maneuver would be, and we had a consumable profile that really left us with reasonable margins at the end,” Lunney said.

Kranz described the scene in an interview with historians at the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station in Australia:

“We had many problems here – we had a variety of survival problems, we had electrical management, water management, and we had to figure out how to navigate because the stars were occluded by the debris cloud surrounding the spacecraft. Basically we had to turn a two day spacecraft into a four and a half day spacecraft with an extra crewmember to get the crew back home. We were literally working outside the design and test boundaries of the spacecraft so we had to invent everything as we went along.”

A look at the transcripts of the conversations between Flight Controllers, Flight Directors and support engineers in the Mission Evaluation Room reveals the methodical working of the problems by the various teams. Additionally, you can see how seamlessly the teams worked together, and when one shift handed off to another, everything was communicated.

Lunney explains:

“The other thing I would say about it is, and we talked about Flight Directors and teams, equally important was the fact that, during those flights, we had this Operations team that you have seen in the Control Center in the back rooms around it and we sort of had our own way of doing things in our own team, and we were fully prepared to decide whatever had to be decided. But in addition to that, we had the engineering design teams that would follow the flight along and look at various problems that occurred and put their own disposition on them. …That was part of this network of support. People had their certain jobs to do. They knew what it was. They knew how they fit in. And they were anticipating and off doing it.”

Without the leadership of the Flight Directors, keeping the teams focused and on-task, the outcome of the Apollo 13 mission may have been much different.

“It is the experience of these two, Kranz and Lunney, working together which likely saved the crew from what might have been certain death,” said Woodfill.

Additional articles in this series:

Part 1: The Failed Oxygen Quantity Sensor

Part 2: Simultaneous Presence of Kranz and Lunney at the Onset of the Rescue

Part 3: Detuning the Saturn V’s 3rd Stage Radio

Part 4: Early Entry into the Lander

Part 5: The CO2 Partial Pressure Sensor

Part 6: The Mysterious Longer-Than-Expected Communications Blackout

Part 7: Isolating the Surge Tank

Part 8: The Indestructible S-Band/Hi-Gain Antenna

Part 10: ‘MacGyvering’ with Everyday Items

Part 11: The Caution and Warning System

Part 12: The Trench Band of Brothers

Find all the original “13 Things That Saved Apollo 13″ (published in 2010) at this link.