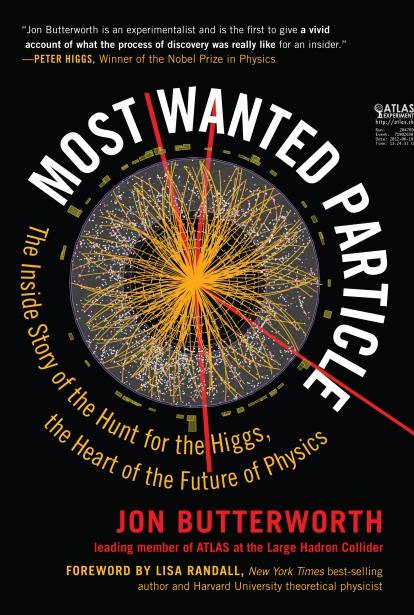

Most Wanted Particle is an insider’s tale of the hunt for the Higgs boson, the field which imparts mass to, well, nearly everything. Written by Jon Butterworth —- a physicist working with the ATLAS team at the Large Hadron Collider —- the book documents the construction of the Large Hadron Collider, the catastrophe after it was first turned on, and the global excitement as evidence for the Higgs boson grew incontrovertible.

Most Wanted Particle has already received glowing praise from the likes of Brian Cox and even Peter Higgs —- for whom the boson is named -— and I’m sure that several physicists reading this site already have the book on their ‘to read’ list. But what about the rest of us? As a biology PhD whose last physics class was about 15 years ago, I decided to see if the book was accessible enough for your average science geek.

Find out how you can win a copy of this book, below.

First and only warning: the book discusses some very fundamental physics, and if you’re afraid to learn about topics like quarks, gluons, and hadronic jets, then this book will be tough going for you (all three of these are introduced on page 22, for instance). This complexity should be largely expected given the subject matter of the book; the alternative would be like a WW2 book that didn’t mention Normandy. So if learning some jargon scares you, you’d best stick to reading the news headlines from CERN.

With that caveat out of the way, Butterworth is a stellar writer and teacher, and he employs a number of tricks to make Most Wanted Particle extremely readable. First of all, equations are largely absent—they are described rather than displayed. (More kudos are due for making it over halfway through the book before the first Feynman diagram appears). Second is Butterworth’s impressive facility with analogy: often, even if you are struggling with the specifics of a concept, you will be able to grasp the broad brush strokes, and that’s enough to follow along with the tale.

Finally, there is the journalistic style. The book is written as a passionate first-person account, and the main narrative is pleasingly interrupted by diversions. It’s not uncommon to have a dense description of, say, super symmetry, broken up by a blog-like chapter discussing an international trip to a conference. (Other topics include meeting etiquette and ‘taking things offline’; what makes a good acronym; and a particularly memorable drunken night for the author and friends in Hamburg.)

Do you have friends who are scientists? If so, you will feel at home reading this book, and it took me a while to understand why. It’s because the general impression that I get from this book is very similar to taking a scientist friend to the pub, and having them describe their work to you over a beer. Sometimes you’ll get a little lost in the more thorny parts of the science; often you’ll get carried off by a tangent; but overall you’ll just enjoy a rollicking good tale, told by an intelligent storyteller.

This book comes highly recommended!

Most Wanted Particle is published by The Experiment Publishing. Find out more about the book here.

Thanks to The Experiment, Universe Today has one copy of this book to give away to our readers. The publisher has specified that for this contest, winners need to be from the US or Canada.

In order to be entered into the giveaway drawing, just put your email address into the box at the bottom of this post (where it says “Enter the Giveaway”) before Monday, April 13, 2015. We’ll send you a confirmation email, so you’ll need to click that to be entered into the drawing. If you’ve entered our giveaways before you should also receive an email with a link on how to enter.