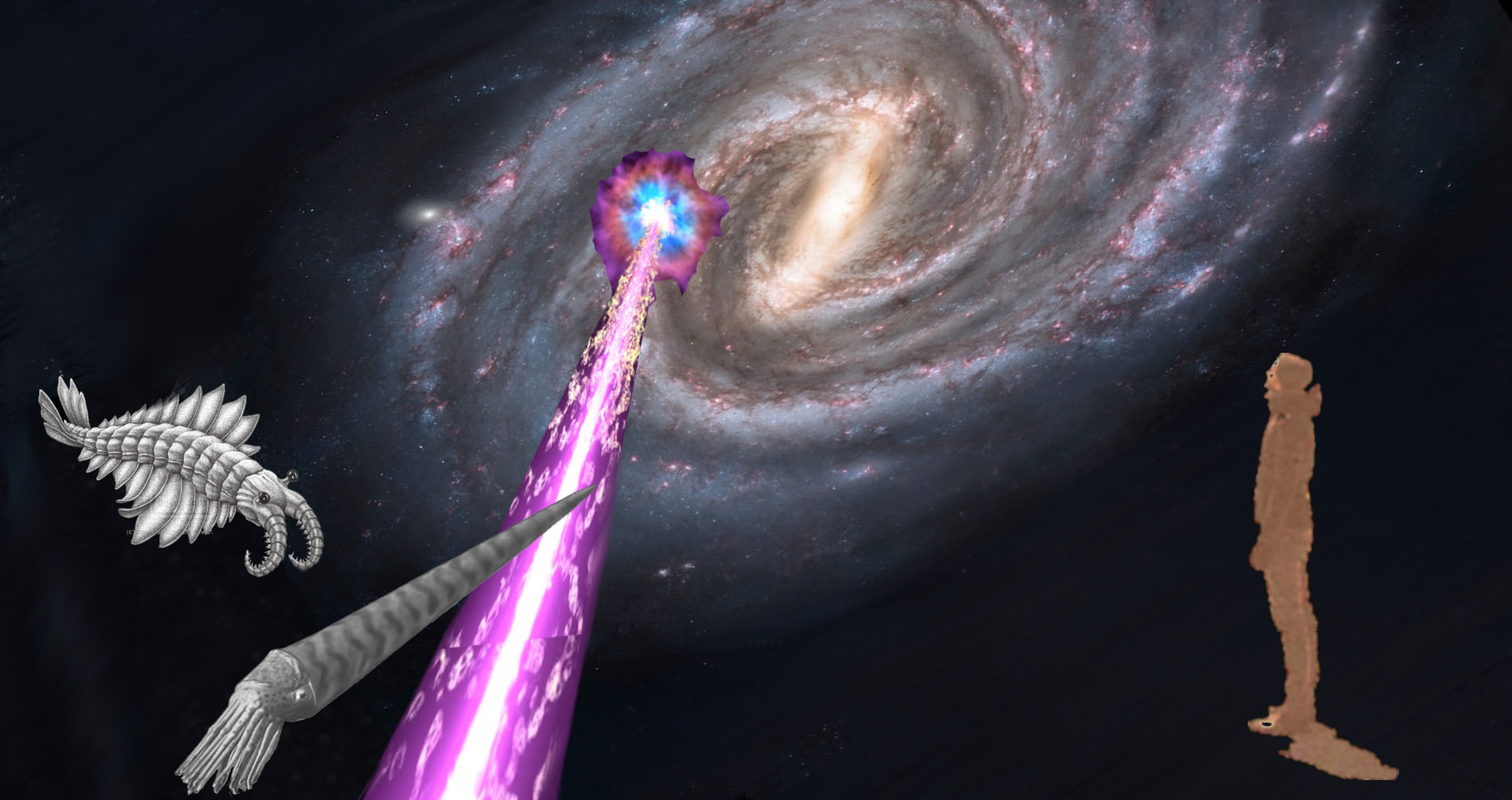

If too close to an environment harboring complex life, a gamma ray burst could spell doom for that life. But could GRBs be the reason we haven’t yet found evidence of other civilizations in the cosmos? To help answer the big question of “where is everybody?” physicists from Spain and Israel have narrowed the time period and the regions of space in which complex life could persist with a low risk of extinction by a GRB.

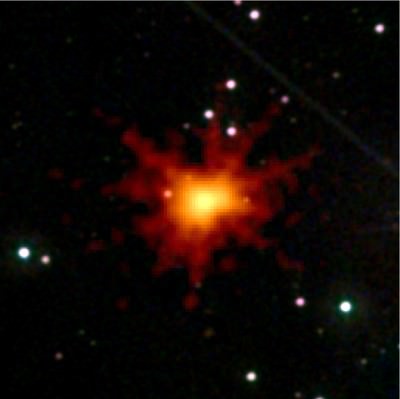

GRBs are some of the most cataclysmic events in the Universe. Astrophysicists are astounded by their intensity, some of which can outshine the whole Universe for brief moments. So far, they have remained incredible far-off events. But in a new paper, physicists have weighed how GRBs could limit where and when life could persist and evolve, potentially into intelligent life.

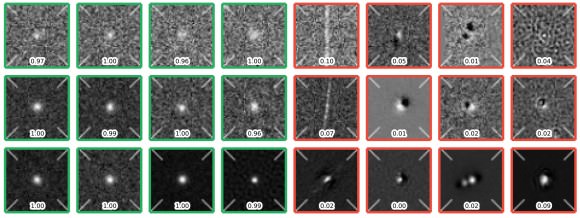

In their paper, “On the role of GRBs on life extinctions in the Universe”, published in the journal Science, Dr. Piran from Hebrew University and Dr. Jimenez from University of Barcelona consider first what is known about gamma ray bursts. The metallicity of stars and galaxies as a whole are directly related to the frequency of GRBs. Metallicity is the abundance of elements beyond hydrogen and helium in the content of stars or whole galaxies. More metals reduce the frequency of GRBs. Galaxies that have a low metal content are prone to a higher frequency of GRBs. The researchers, referencing their previous work, state that observational data has shown that GRBs are not generally related to a galaxy’s star formation rate; forming stars, including massive ones is not the most significant factor for increased frequency of GRBs.

As fate would have it, we live in a high metal content galaxy – the Milky Way. Piran and Jimenez show that the frequency of GRBs in the Milky Way is lower based on the latest data available. That is the good news. More significant is the placement of a solar system within the Milky Way or any galaxy.

The paper states that there is a 50% chance of a lethal GRB’s having occurred near Earth within the last 500 million years. If a stellar system is within 13,000 light years (4 kilo-parsecs) of the galactic center, the odds rise to 95%. Effectively, this makes the densest regions of all galaxies too prone to GRBs to permit complex life to persist.

The Earth lies at 8.3 kilo-parsecs (27,000 light years) from the galactic center and the astrophysicists’ work also concludes that the chances of a lethal GRB in a 500 million year span does not drop below 50% until beyond 10 kilo-parsecs (32,000 light years). So Earth’s odds have not been most favorable, but obviously adequate. Star systems further out from the center are safer places for life to progress and evolve. Only the outlying low star density regions of large galaxies keep life out of harm’s way of gamma ray bursts.

The paper continues by describing their assessment of the effect of GRBs throughout the Universe. They state that only approximately 10% of galaxies have environments conducive to life when GRB events are a concern. Based on previous work and new data, galaxies (their stars) had to reach a metallicity content of 30% of the Sun’s, and the galaxies needed to be at least 4 kilo-parsecs (13,000 light years) in diameter to lower the risk of lethal GRBs. Simple life could survive repeated GRBs. Evolving to higher life forms would be repeatedly set back by mass extinctions.

Piran’s and Jimenez’s work also reveals a relation to a cosmological constant. Further back in time, metallicity within stars was lower. Only after generations of star formation – billions of years – have heavier elements built up within galaxies. They conclude that complex life such as on Earth – from jelly fish to humans – could not have developed in the early Universe before Z > 0.5, a cosmological red-shift equal to ~5 billion years ago or longer ago. Analysis also shows that there is a 95% chance that Earth experienced a lethal GRB within the last 5 billion years.

The question of what effect a nearby GRB could have on life has been raised for decades. In 1974, Dr. Malvin Ruderman of Columbia University considered the consequences of a nearby supernova on the ozone layer of the Earth and on terrestrial life. His and subsequent work has determined that cosmic rays would lead to the depletion of the ozone layer, a doubling of the solar ultraviolet radiation reaching the surface, cooling of the Earth’s climate, and an increase in NOx and rainout that effects biological systems. Not a pretty picture. The loss of the ozone layer would lead to a domino effect of atmospheric changes and radiation exposure leading to the collapse of ecosystems. A GRB is considered the most likely cause of the mass extinction at the end of the Ordovician period, 450 million years ago; there remains considerable debate on the causes of this and several other mass extinction events in Earth’s history.

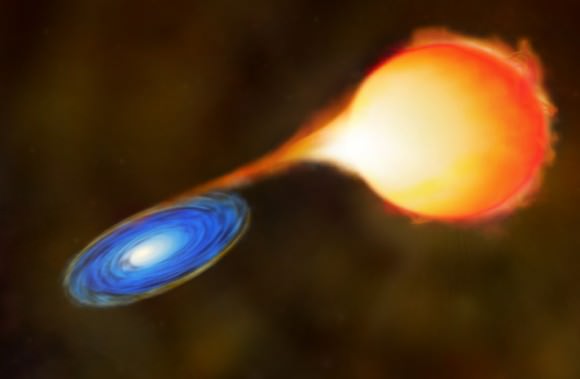

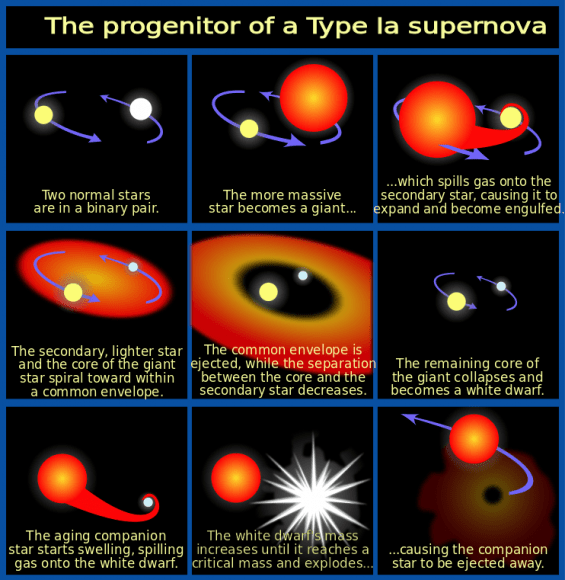

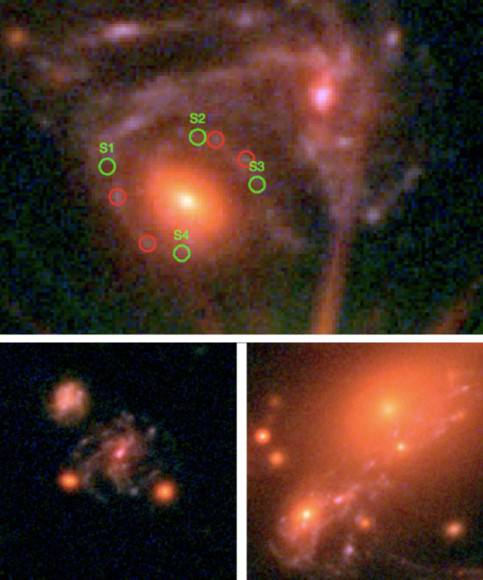

The paper focuses on what are deemed long GRBs – lGRBs – lasting several seconds in contrast to short GRBs which last only a second or less. Long GRBs are believed to be due to the collapse of massive stars such as seen in supernovas, while sGRBs are from the collision of neutron stars or black holes. There remains uncertainty as to the causes, but the longer GRBs release far greater amounts of energy and are most dangerous to ecosystems harboring complex life.

The paper narrows the time and space available for complex life to develop within our Universe. Over the age of the Universe, approximately 14 billion years, only the last 5 billion years have been conducive to the creation of complex life. Furthermore, only 10% of the galaxies within the last 5 billion years provided such environments. And within only larger galaxies, only the outlying areas provided the safe distances needed to evade lethal exposure to a gamma ray burst.

This work reveals how well our Solar System fits within the ideal conditions for permitting complex life to develop. We stand at a fairly good distance from the Milky Way’s galactic center. The age of our Solar System, at approximately 4.6 billion years, lies within the 5 billion year safe zone in time. However, for many other stellar systems, despite how many are now considered to exist throughout the Universe – 100s of billions in the Milky Way, trillions throughout the Universe – simple is probably a way of life due to GRBs. This work indicates that complex life, including intelligent life, is likely less common when just taking the effect of gamma ray bursts into consideration.

References:

On the role of GRBs on life extinction in the Universe, Tsvi Piran, Raul Jimenez, Science, Nov 2014, pre-print