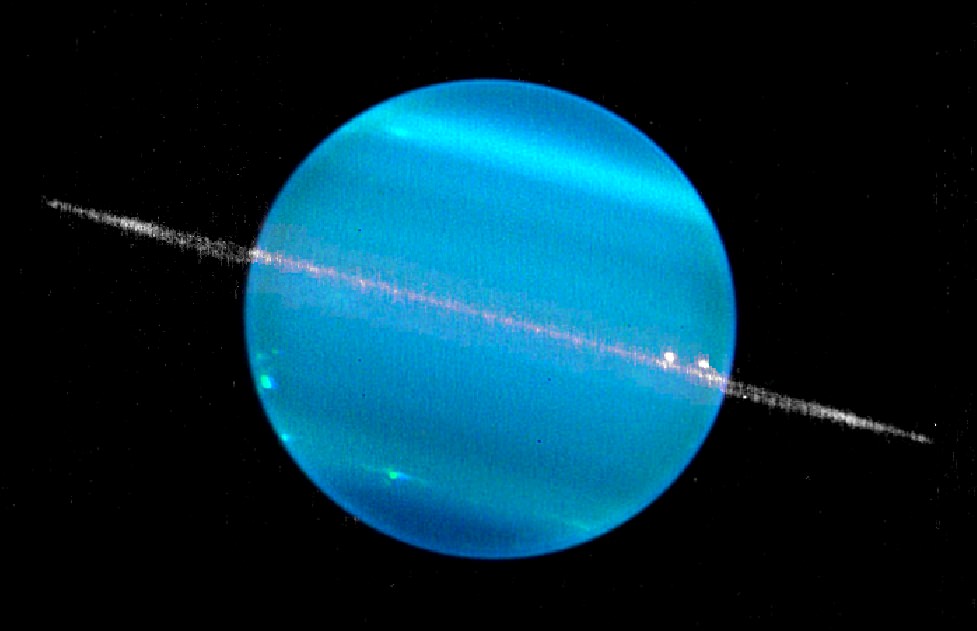

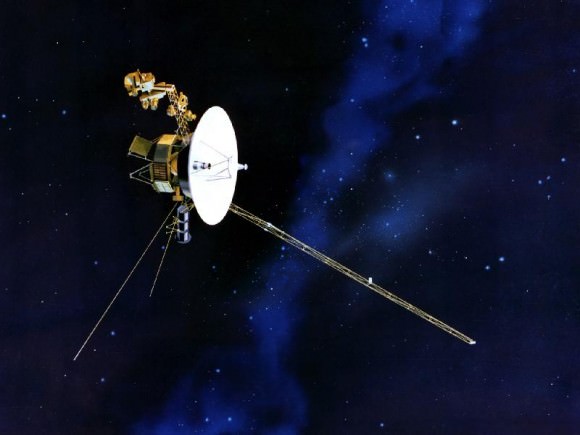

Sometimes first impressions are poor ones. When the Voyager 2 spacecraft whizzed by Uranus in 1986, the close-up view of the gas giant revealed what appeared to a be a relatively featureless ball. By that point, scientists were used to seeing bright colors and bands on Jupiter and Saturn. Uranus wasn’t quite deemed uninteresting, but the lack of activity was something that was usually remarked upon when describing the planet.

Fast-forward 28 years and we are learning that Uranus is a more complex world than imagined at the time. Two new studies, discussed at an American Astronomical Society meeting today, show that Uranus is a stormy place and also that the images from Voyager 2 had more interesting information than previously believed.

Showing the value of going over old data, University of Arizona astronomer Erich Karkoschka reprocessed old images of Voyager 2 data — including stacking 1,600 pictures on top of each other.

He found elements of Uranus’ atmosphere that reveals the southern hemisphere moves differently than other regions in fellow gas giants. Since only the top 1% of the atmosphere is easily observable from orbit, scientists try to make inferences about the 99% that lie underneath by looking at how the upper atmosphere behaves.

“Some of these features probably are convective clouds caused by updraft and condensation. Some of the brighter features look like clouds that extend over hundreds of kilometers,” he stated in a press release.

“The unusual rotation of high southern latitudes of Uranus is probably due to an unusual feature in the interior of Uranus,” he added. “While the nature of the feature and its interaction with the atmosphere are not yet known, the fact that I found this unusual rotation offers new possibilities to learn about the interior of a giant planet.”

It’s difficult to get more information about the inner atmosphere without sending down a probe, but other methods of getting a bit of information include using radio (which shows magnetic field rotation) or gravitational fields. The university stated that Karkoschka’s work could help improve models of Uranus’ interior.

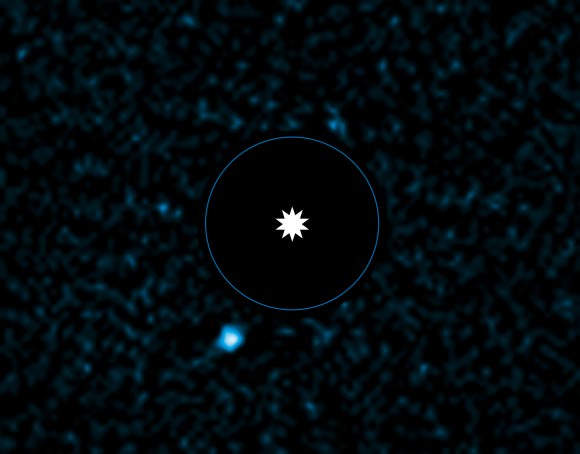

So that was Uranus three decades ago. What about today? Turns out that storms are popping up on Uranus that are so large that for the first time, amateur astronomers can track them from Earth. A separate study on Uranus shows the planet is “incredibly active”, and what’s more, it took place at an unexpected time.

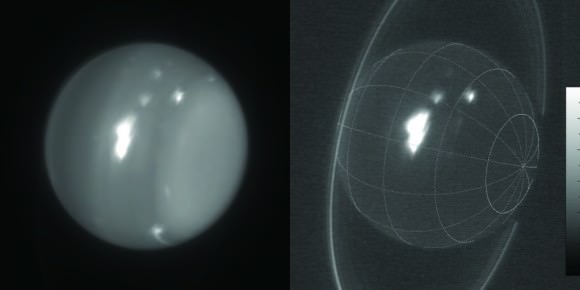

Summer happened in 2007 when the Sun shone on its equator, which should have produced more heat and stormy weather at the time. (Uranus has no internal heat source, so the Sun is believed to be the primary driver of energy on the planet.) However, a team led by Imke de Pater, chair of astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley, spotted eight big storms in the northern hemisphere while looking at the planet with the Keck Telescope on Aug. 5 and 6.

Keck’s eye revealed a big, bright storm that represented 30% of light reflected by the planet at a wavelength of 2.2 microns, which provides information about clouds below the tropopause. Amateurs, meanwhile, spotted a storm of a different sort. Between September and October, several observations were reported of a storm at 1.6 microns, deeper in the atmosphere.

“The colors and morphology of this [latter] cloud complex suggests that the storm may be tied to a vortex in the deeper atmosphere similar to two large cloud complexes seen during the equinox,” stated Larry Sromovsky, a planetary scientist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

What is causing the storms now is still unknown, but the team continues to watch the Uranian weather to see what will happen next. Results from both studies were presented at the Division for Planetary Sciences meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Tucson, Arizona today. Plans for publication and whether the research was peer-reviewed were not disclosed in press releases concerning the findings.