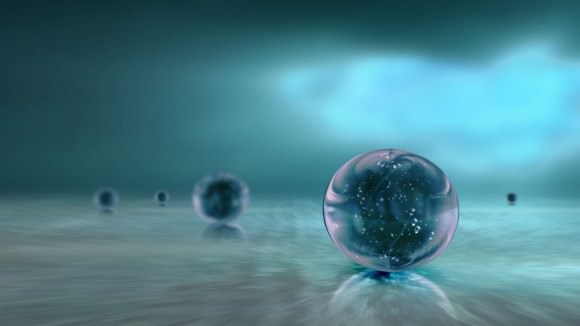

Imagine if you were told that the world is simple and exactly as it seems, but that there is an infinite number of worlds just like ours. They share the same space and time, and interact with each other. These worlds behave as Newton first envisioned, except that the slightest interactions of the infinite number create nuances and deviations from the Newtonian mechanics. What could be deterministic is swayed by many worlds to become the unpredictable.

This is the new theory about parallel universes explained by Australian and American theorists in a paper published in the journal Physics Review X. Called the “Many Interacting Worlds” theory (MIW), the paper explains that rather than standing apart, an infinite number of universes share the same space and time as ours. They show that their theory can explain quantum mechanical effects while leaving open the choice of theory to explain the universe at large scales. This is a fascinating new variant of Multiverse Theory that, in a sense, creates not just a doppelganger of everyone but an infinite number of them all overlaying each other in the same space and time.

Cosmology is a study in which practitioners must transcend their five senses. Einstein referred to thought experiments, and Dr. Stephen Hawking — surviving and persevering despite having ALS — has spent decades wondering about the Universe and developing new theories, all within his mind.

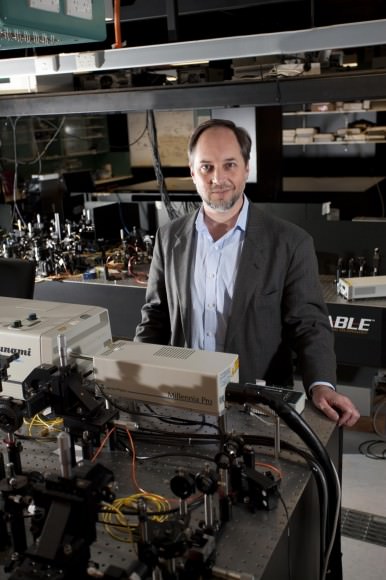

The “Many Interacting Worlds” theory, presented by Michael Hall and Howard Wiseman from Griffith University in Australia, and Dirk-André Deckert from the University of California, Davis, differs from previous multiverse theories in that the worlds — as they refer to universes — coincide with each other, and are not just parallel.

The theorists explain that while the interactions are subtle, the interaction of an infinite number of worlds can explain quantum phenomena such as barrier tunneling in solid state electronics, can be used to calculate quantum ground states, and, as they state, “at least qualitatively” reproduce the results of the double-slit experiment.

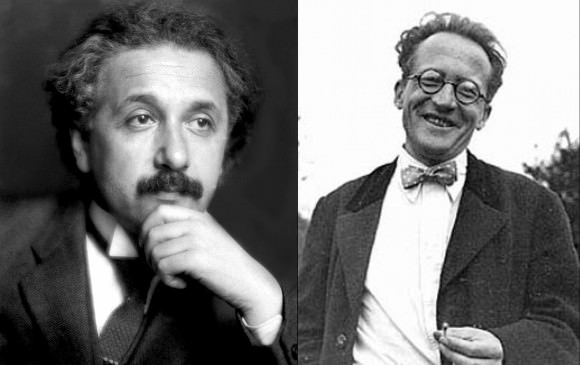

Schrödinger, in explaining his wave function and the interaction of two particles (EPR paradox) coined the term “entanglement”. In effect, the MIW theory is an entanglement of an infinite number of worlds but not in terms of a wave function. The theorists state that they were compelled to develop MIW theory to eliminate the need for a wave function to explain the Universe. It is quite likely that Einstein would have seen MIW as very appealing considering his unwillingness to accept the principles laid down by the Copenhagen interpretation of Quantum Theory.

While MIW theory can reproduce some of the most distinctive quantum phenomena, the theorists emphasize that MIW is in an early phase of development. They state that the theory is not yet as mature as long-standing unification theories. In their paper, they use Newtonian physics to keep their proofs simple. Presenting this new “many worlds” theory indicates they had achieved a level of confidence in its integrity such that other theorists can use it as a starter kit – peer review but also expand upon it to explain more worldly phenomena.

Hall compares MIW to the classical theory of ideal gases and partial pressures. He says:

Two worlds of many act as if they are two gases A & B within a volume of space. In the words of the theorists, “It would be as if the A gas and B gas were completely oblivious to each other unless every single A molecule were close to its B partner. Such an interaction is quite unlike anything in classical physics, and it is clear that our hypothetical A-composed observer would have no experience of the B world in its everyday observations, but by careful experiment might detect a subtle and nonlocal action on the A molecules of its world. Such action, though involving very many, rather than just two, worlds, is what we propose could lie behind the subtle and nonlocal character of quantum mechanics.”

The theorists continue by expounding that MIW could lead to new predictions. If correct, then new predictions would challenge experimentalists and observers to recreate or search for the effects. Such was the case for Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. For example, the bending of the path of light by gravity and astronomer Eddington’s observing starlight bending around Sun during a total Solar Eclipse. Such new predictions and confirmation would begin to stand MIW theory apart from the many other theories of everything.

Hall, Deckert, and Wiseman continue – “Regarded as a fundamental physical theory in its own right, the MIW approach may also lead to new predictions arising from the restriction to a finite number of worlds. Finally, it provides a natural discretization of the Holland-Poirier approach, which may be useful for numerical purposes.”

Multiverse theories have gained notoriety in recent years through the books and media presentations of Dr. Michio Kaku of the City College of New York and Dr. Brian Greene of Columbia University, New York City. Dr. Green presented a series of episodes delving into the nature of the Universe on PBS called “The Fabric of the Universe” and “The Elegant Universe”. The presentations were based on his books such as “The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos.”

Hugh Everett’s reinterpretation of Dr. Richard Feynman’s cosmological theory, that the world is a weighted sum of alternative histories, states that when particles interact, reality bifurcates into a set of parallel streams, each being a different possible outcome. In contrast to Feynmann’s theory and Everett’s interpretation, the parallel worlds of MIW do not bifurcate but simply exist in the same space and time. MIW’s parallel worlds are not a consequence of “quantum behavior” but are rather the drivers of it.

Hall states in the paper that simple Newtonian Physics can explain how all these worlds evolve. This, they explain, can be used effectively as a first approximation in testing and expanding on their theory, MIW. Certainly, Einstein’s Special and General Theories of Relativity completes the Newtonian equations and are not dismissed by MIW. However, the paper begins with the simpler model using Newtonian physics and even explains that some fundamental behavior of quantum mechanics unfolds from a universe comprised of just two interacting worlds.

So what is next for the Many Interacting Worlds theory? Time will tell. Theorists and experimentalists shall begin to evaluate its assertions and its solutions to explain known behavior in our Universe. With new predictions, the new challenger to Unified Field Theory (the theory of everything) will be harder to ignore or file away with the wide array of theories of the last 100 years. Einstein’s theories began to reveal that our world exudes behavior that defies our sensibility but he could not accept the assertions of Quantum Theory. Einstein’s retort to Bohr was “God does not throw dice.” The MIW theory of Hall, Deckert, and Wiseman might be what Einstein was seeking until the end of his life. For MIW theory, one world is not enough and for these many worlds their interactions might be compared to a martini shaken but not stirred.

References:

Quantum Phenomena Modeled by Interactions between Many Classical Worlds