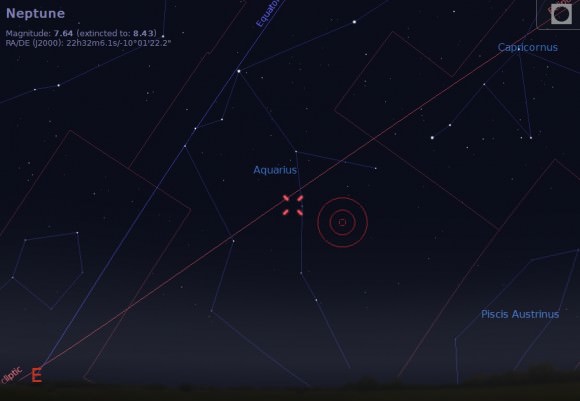

Never seen Neptune? Now is a good time to try, as the outermost ice giant world reaches opposition this weekend at 14:00 Universal Time (UT) or 10:00 AM EDT on Friday, August 29th. This means that the distant world lies “opposite” to the Sun as seen from our Earthly perspective and rises to the east as the Sun sets to the west, riding high in the sky across the local meridian near midnight.

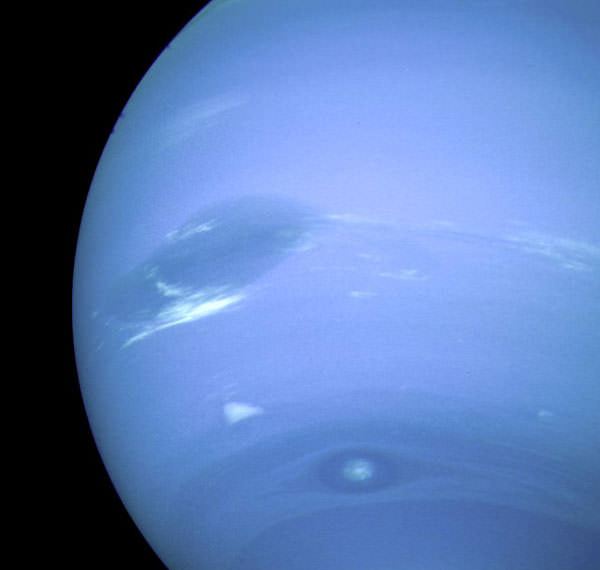

2014 finds Neptune shining at magnitude +7.6 in the constellation of Aquarius. Unfortunately, the planet is too faint to be seen with the naked eye, but can be sighted using a good pair of binoculars if know exactly where to look for it. Though the telescope, Neptune exhibits a tiny blue-gray disk 2.4” across — 750 “Neptunes” would fit across the apparent diameter of the Full Moon — that’s barely discernible. Don’t be afraid to crank up the magnification in your quest. We’ve found Neptune on years previous by patently examining suspect stars one by one, looking for the one in the field that stubbornly refuses to focus to a star-like point. Make sure your optics are well collimated to attempt this trick. Neptune will exhibit a tiny fuzzy disk, much like a second-rate planetary nebula. In fact, this is where “planetaries” get their moniker, as the pesky deep sky objects resembled planets in those telescopes of yore…

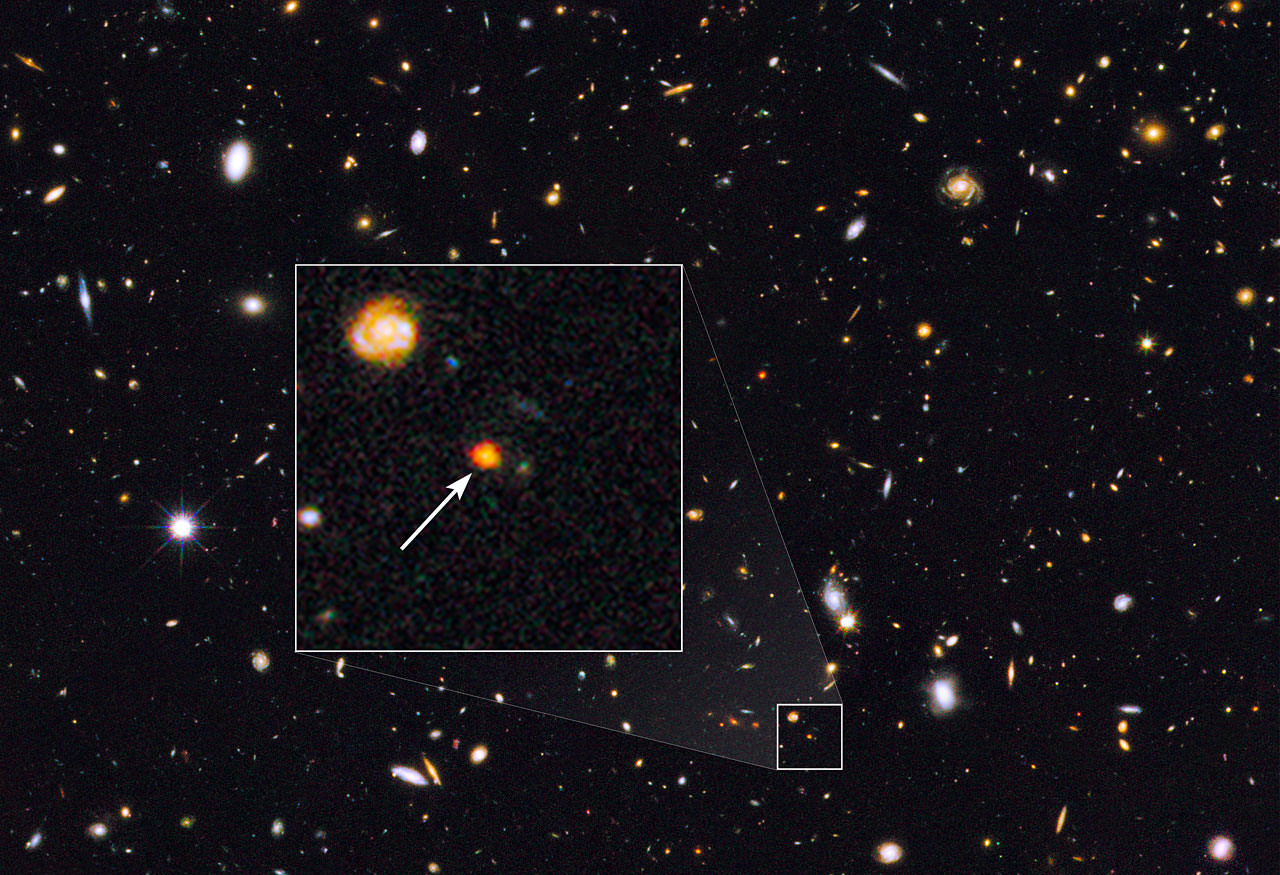

The 1846 discovery of Neptune stood as a vindication of the (then) new-fangled theory of Newtonian gravitational dynamics. Uranus was discovered just decades before by Sir William Hershel in 1781, and it stubbornly refused to follow predictions concerning its position. French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier correctly assumed that an unseen body was tugging on Uranus, predicted the position of the suspect object in the sky, and the race was on. On the night of September 24th, Heinrich Louis d’Arrest and Johann Gottfried Galle observing from the Berlin observatory became the first humans to gaze upon the new world referring to it as such. Did you know: Galileo actually sketched Neptune near Jupiter in 1612? And those early 18th century astronomers got a lucky break… had Neptune happened to have been opposite to Uranus in its orbit, it might’ve eluded discovery for decades to come!

It’s also sobering to think that Neptune has only recently completed a single orbit of the Sun in 2011 since its discovery. Opposition of Neptune occurs once every 368 days, meaning that opposition is slowly moving forward by about three days a year on our Gregorian calendar and will soon start occurring in northern hemisphere Fall.

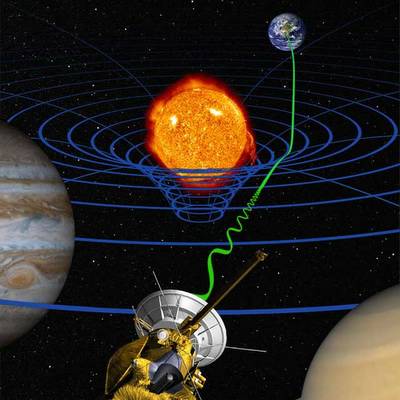

Now for the “wow factor” of what you’re actually seeing. Though tiny, Neptune is actually 24,622 kilometres in radius, and is 58 times as big as the Earth in volume and over 17 times as massive. Neptune is 29 A.U.s or 4.3 billion kilometres from Earth at opposition, meaning the light we see took almost four hours to transit from Neptune to your backyard.

Neptune is currently south of the equator, and won’t be north of it again until 2027.

Next month, keep an eye on Neptune as it passes less than half a degree north of the +4.8 magnitude star Sigma Aquarii through mid-September, making a great guide to find the planet…

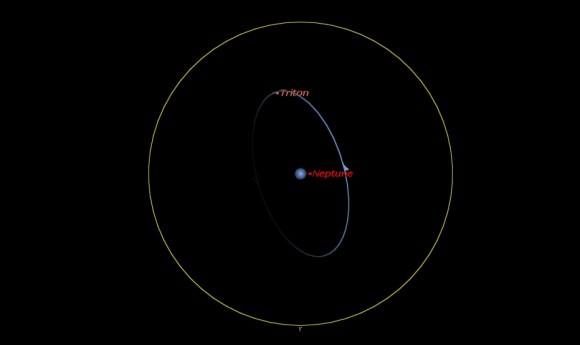

Still not enough of a challenge? Try tracking down Neptune’s large moon, Triton. Orbiting the planet in a retrograde path once every 5.9 days, Triton is within reach of a large backyard scope at magnitude +14. Triton never strays more than 15” from the disk of Neptune, but opposition is a great time to cross this curious moon off of your observing life list. Neptune has 14 moons at last count.

And speaking of Triton, NASA recently released a new map of the moon. We’ve only gotten one good look at Triton, Neptune, and its retinue of moons back in 1989 when Voyager 2 conducted the only flyby of the planet to date. Will Pluto turn out to be Triton’s twin when New Horizons completes its historic flyby next summer?

The Moon also passes 4.3 degrees north of Neptune on September 8th on its way to “Supermoon 3 of 3” for 2014 on the night of September 8th/9th. Fun fact: a cycle of occultations of Neptune by the Moon commences on June 2016.

When will we explore Neptune once more? Will a dedicated “Neptune orbiter” ever make its way to the planet in our lifetimes? All fun things to ponder as you check out the first planet discovered using scientific reasoning this weekend.