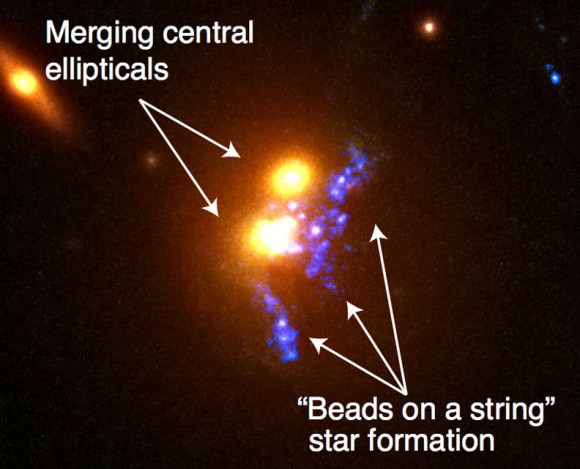

On a summer night, high above our heads, where the Northern Crown and Herdsman meet, a titanic new galaxy is being born 4.5 billion light years away. You and I can’t see it, but astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope released photographs today showing the merger of two enormous elliptical galaxies into a future heavyweight adorned with a dazzling string of super-sized star clusters.

The two giants, each about 330,000 light years across or more than three times the size of the Milky Way, are members of a large cluster of galaxies called SDSS J1531+3414. They’ve strayed into each other’s paths and are now helpless against the attractive force of gravity which pulls them ever closer.

Galactic mergers are violent events that strip gas, dust and stars away from the galaxies involved and can alter their appearances dramatically, forming large gaseous tails, glowing rings, and warped galactic disks. Stars on the other hand, like so many pinpoints in relatively empty space, pass by one another and rarely collide.

Elliptical galaxies get their name from their oval and spheroidal shapes. They lack the spiral arms, rich reserves of dust and gas and pizza-like flatness that give spiral galaxies like Andromeda and the Milky Way their multi-faceted character. Ellipticals, although incredibly rich in stars and globular clusters, generally appear featureless.

But these two monster ellipticals appear to be different. Unlike their gas-starved brothers and sisters, they’re rich enough in the stuff needed to induce star formation. Take a look at that string of blue blobs stretching across the center – astronomers call it a great example of ‘beads on a string’ star formation. The knotted rope of gaseous filaments with bright patches of new star clusters stems from the same physics which causes rain or water from a faucet to fall in droplets instead of streams. In the case of water, surface tension makes water ‘snap’ into individual droplets; with clouds of galactic gas, gravity is the great congealer.

Nineteen compact clumps of young stars make up the length of this ‘string’, woven together with narrow filaments of hydrogen gas. The star formation spans 100,000 light years, about the size of our galaxy, the Milky Way. Astronomers still aren’t sure if the gas comes directly from the galaxies or has condensed like rain from X-ray-hot halos of gas surrounding both giants.

The blue arcs framing the merger have to do with the galaxy cluster’s enormous gravity, which warps the fabric of space like a lens, bending and focusing the light of more distant background galaxies into curvy strands of blue light. Each represents a highly distorted image of a real object.

Simulation of the Milky Way-Andromeda collision 4 billion years from now

Four billion years from now, Milky Way residents will experience a merger of our own when the Andromeda Galaxy, which has been heading our direction at 300,000 mph for millions of years, arrives on our doorstep. After a few do-si-dos the two galaxies will swallow one another up to form a much larger whirling dervish that some have already dubbed ‘Milkomeda’. Come that day, perhaps our combined galaxies will don a string a blue pearls too.