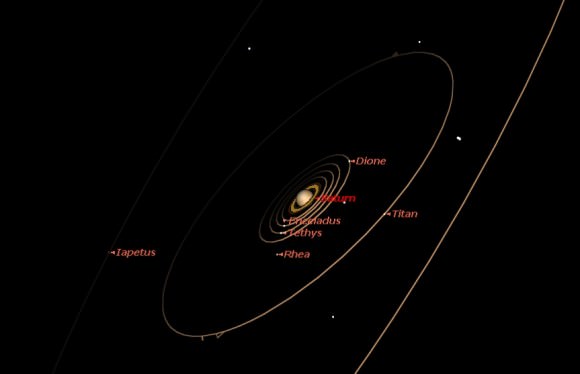

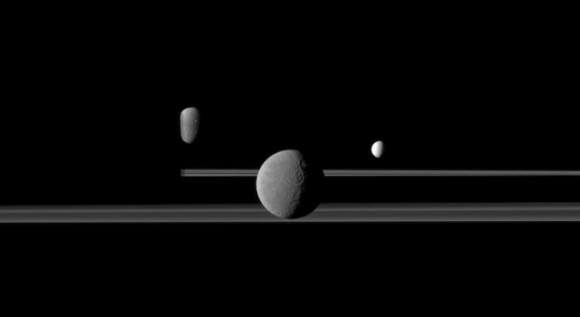

Saturn is well known for being a gas giant, and for its impressive ring system. But would it surprise you to know that this planet also has the second-most moons in the Solar System, second only to Jupiter? Yes, Saturn has at least 150 moons and moonlets in total, though only 62 have confirmed orbits and only 53 have been given official names.

Most of these moons are small, icy bodies that are little more than parts of its impressive ring system. In fact, 34 of the moons that have been named are less than 10 km in diameter while another 14 are 10 to 50 km in diameter. However, some of its inner and outer moons are among the largest and most dramatic in the Solar System, measuring between 250 and 5000 km in diameter and housing some of the greatest mysteries in the Solar System.

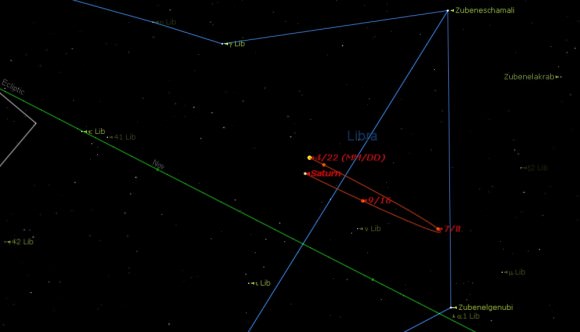

Saturn’s moons have such a variety of environments between them that you’d be forgiven for wanting to spend an entire mission just looking at its satellites. From the orange and hazy Titan to the icy plumes emanating from Enceladus, studying Saturn’s system gives us plenty of things to think about. Not only that, the moon discoveries keep on coming. As of April 2014, there are 62 known satellites of Saturn (excluding its spectacular rings, of course). Fifty-three of those worlds are named.

Discovery and Naming

Prior to the invention of telescopic photography, eight of Saturn’s moons were observed using simple telescopes. The first to be discovered was Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, which was observed by Christiaan Huygens in 1655 using a telescope of his own design. Between 1671 and 1684, Giovanni Domenico Cassini discovered the moons of Tethys, Dione, Rhea, and Iapetus – which he collectively named the “Sider Lodoicea” (Latin for “Louisian Stars”, after King Louis XIV of France).

n 1789, William Herschel discovered Mimas and Enceladus, while father-and-son astronomers W.C Bond and G.P. Bond discovered Hyperion in 1848 – which was independently discovered by William Lassell that same year. By the end of the 19th century, the invention of long-exposure photographic plates allowed for the discovery of more moons – the first of which Phoebe, observed in 1899 by W.H. Pickering.

In 1966, the tenth satellite of Saturn was discovered by French astronomer Audouin Dollfus, which was later named Janus. A few years later, it was realized that his observations could only be explained if another satellite had been present with an orbit similar to that of Janus. This eleventh moon was later named Epimetheus, which shares the same orbit as Janus and is the only known co-orbital in the Solar System.

By 1980, three additional moons were discovered and later confirmed by the Voyager probes. They were the trojan moons (see below) of Helene (which orbits Dione) as well as Telesto and Calypso (which orbit Tethys).

The study of the outer planets has since been revolutionized by the use of unmanned space probes. This began with the arrival of the Voyager spacecraft to the Cronian system in 1980-81, which resulted in the discovery of three additional moons – Atlas, Prometheus, and Pandora – bringing the total to 17. By 1990, archived images also revealed the existence of Pan.

This was followed by the Cassini-Huygens mission, which arrived at Saturn in the summer of 2004. Initially, Cassini discovered three small inner moons, including Methone and Pallene between Mimas and Enceladus, as well as the second Lagrangian moon of Dione – Polydeuces. In November of 2004, Cassini scientists announced that several more moons must be orbiting within Saturn’s rings. From this data, multiple moonlets and the moons of Daphnis and Anthe have been confirmed.

The study of Saturn’s moons has also been aided by the introduction of digital charge-coupled devices, which replaced photographic plates by the end of the 20th century. Because of this, ground-based telescopes have begun to discover several new irregular moons around Saturn. In 2000, three medium-sized telescopes found thirteen new moons with eccentric orbits that were of considerable distance from the planet.

In 2005, astronomers using the Mauna Kea Observatory announced the discovery of twelve more small outer moons. In 2006, astronomers using Japan’s Subaru Telescope at Mauna Kea reported the discovery of nine more irregular moons. In April of 2007, Tarqeq (S/2007 S 1) was announced, and in May of that same year, S/2007 S 2 and S/2007 S 3 were reported.

The modern names of Saturn’s moons were suggested by John Herschel (William Herschel’s son) in 1847. In keeping with the nomenclature of the other planets, he proposed they be named after mythological figures associated with the Roman god of agriculture and harvest – Saturn, the equivalent of the Greek Cronus. In particular, the seven known satellites were named after Titans, Titanesses and Giants – the brothers and sisters of Cronus.

In 1848, Lassell proposed that the eighth satellite of Saturn be named Hyperion after another Titan. When in the 20th century, the names of Titans were exhausted, the moons were named after different characters of the Greco-Roman mythology, or giants from other mythologies. All the irregular moons (except Phoebe) are named after Inuit and Gallic gods and Norse ice giants.

Saturn’s Inner Large Moons

Saturn’s moons are grouped based on their size, orbits, and proximity to Saturn. The innermost moons and regular moons all have small orbital inclinations and eccentricities and prograde orbits. Meanwhile, the irregular moons in the outermost regions have orbital radii of millions of kilometers, orbital periods lasting several years, and move in retrograde orbits.

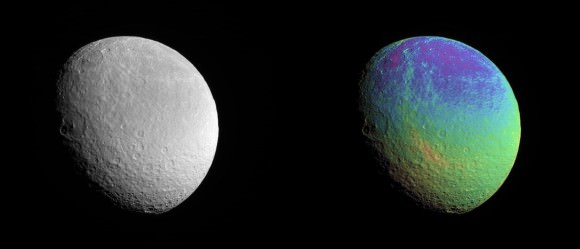

Saturn’s Inner Large Moons, which orbit within the E Ring (see below), include the larger satellites Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, and Dione. These moons are all composed primarily of water ice and are believed to be differentiated into a rocky core and an icy mantle and crust. With a diameter of 396 km and a mass of 0.4×1020 kg, Mimas is the smallest and least massive of these moons. It is ovoid in shape and orbits Saturn at a distance of 185,539 km with an orbital period of 0.9 days.

Some people jokingly call Mimas the “Death Star” moon because of the crater on its surface that resembles the machine from the Star Wars universe. The 140 km (88 mi) Herschel Crater is about a third the diameter of the moon itself and could have created fractures (chasmata) on the moon’s opposing side. There are in fact craters throughout the moon’s small surface, making it among the most pockmarked in the Solar System.

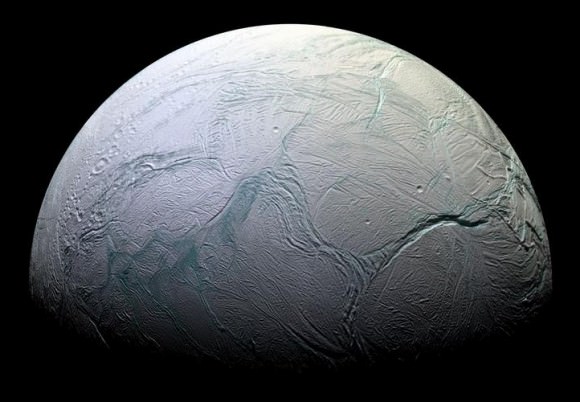

Enceladus, meanwhile, has a diameter of 504 km, a mass of 1.1×1020 kg, and is spherical in shape. It orbits Saturn at a distance of 237,948 km and takes 1.4 days to complete a single orbit. Though it is one of the smaller spherical moons, it is the only Cronian moon that is endogenously active – and one of the smallest known bodies in the Solar System that is geologically active. This results in features like the famous “tiger stripes” – a series of continuous, ridged, slightly curved, and roughly parallel faults within the moon’s southern polar latitudes.

Large geysers have also been observed in the southern polar region that periodically releases plumes of water ice, gas, and dust which replenish Saturn’s E ring. These jets are one of several indications that Enceladus has liquid water beneath its icy crust, where geothermal processes release enough heat to maintain a warm water ocean closer to its core.

The moon has at least five different kinds of terrain, a “young” geological surface of less than 100 million years. With a geometrical albedo of more than 140%, which is due to it being composed largely of water ice, Enceladus is one of the brightest known objects in the Solar System.

At 1066 km in diameter, Tethys is the second-largest of Saturn’s inner moons and the 16th-largest moon in the Solar System. The majority of its surface is made up of heavily cratered and hilly terrain and a smaller and smoother plains region. Its most prominent features are the large impact crater of Odysseus, which measures 400 km in diameter, and a vast canyon system named Ithaca Chasma – which is concentric with Odysseus and measures 100 km wide, 3 to 5 km deep, and 2,000 km long.

With a diameter and mass of 1,123 km and 11×1020 kg, Dione is the largest inner moon of Saturn. The majority of Dione’s surface is heavily cratered old terrain, with craters that measure up to 250 km in diameter. However, the moon is also covered with an extensive network of troughs and lineaments which indicate that in the past it had global tectonic activity.

It’s covered in canyons, crackings, craters, and is coated from dust in the E-ring that originally came from Enceladus. The location of this dust has led astronomers to theorize that the moon was spun about 180 degrees from its original disposition in the past, perhaps due to a large impact.

Saturn’s Large Outer Moons:

The Large Outer Moons, which orbit outside of the Saturn’s E Ring, are similar in composition to the Inner Moons – i.e. composed primarily of water ice, and rock. Of these, Rhea is the second-largest – measuring 1,527 km in diameter and 23×1020 kg in mass – and the ninth-largest moon in the Solar System. With an orbital radius of 527,108 km, it is the fifth-most distant of the larger moons and takes 4.5 days to complete an orbit.

Like other Cronian satellites, Rhea has a rather heavily cratered surface and a few large fractures on its trailing hemisphere. Rhea also has two very large impact basins on its anti-Saturnian hemisphere – the Tirawa crater (similar to Odysseus on Tethys) and the Inktomi crater – which measure about 400 and 50 km across, respectively.

Rhea has at least two major sections, the first being bright craters with craters larger than 40 km (25 miles), and a second section with smaller craters. The difference in these features is believed to be evidence of a major resurfacing event at some time in Rhea’s past.

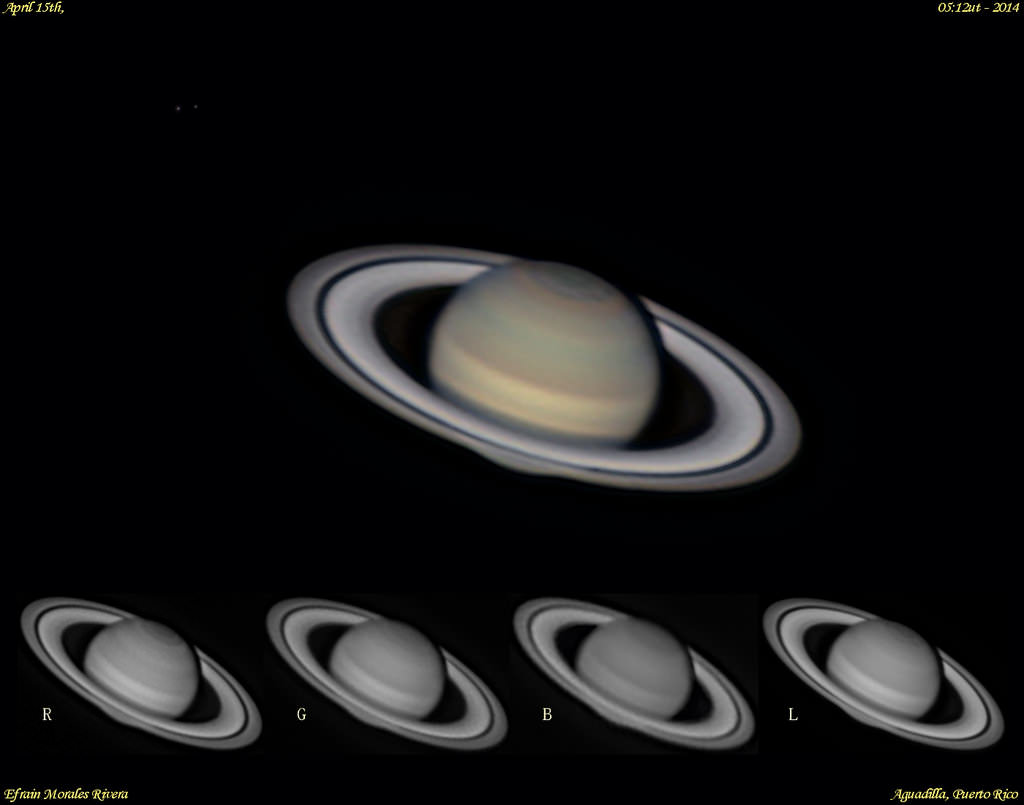

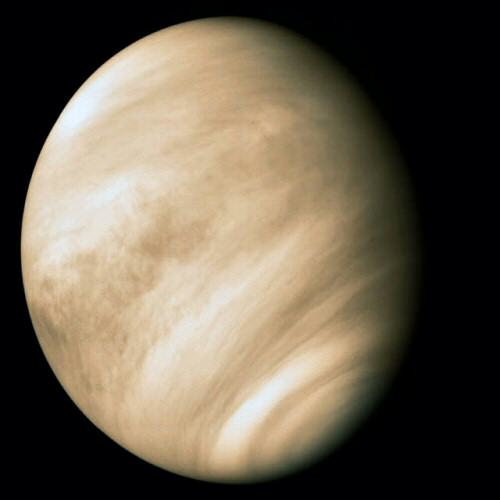

At 5150 km in diameter and 1,350×1020 kg in mass, Titan is Saturn’s largest moon and comprises more than 96% of the mass in orbit around the planet. Titan is also the only large moon to have its own atmosphere, which is cold, dense, and composed primarily of nitrogen with a small fraction of methane. Scientists have also noted the presence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the upper atmosphere, as well as methane ice crystals.

The surface of Titan, which is difficult to observe due to persistent atmospheric haze, shows only a few impact craters, evidence of cryovolcanoes, and longitudinal dune fields that were apparently shaped by tidal winds. Titan is also the only body in the Solar System besides Earth with bodies of liquid on its surface, in the form of methane–ethane lakes in Titan’s north and south polar regions.

Titan is also distinguished for being the only Cronian moon that has ever had a probe land on it. This was the Huygens lander, which was carried to the hazy world by the Cassini spacecraft. Titan’s “Earth-like processes” and thick atmosphere are among the things that make this world stand out to scientists, which include its ethane and methane rains from the atmosphere and flows on the surface.

With an orbital distance of 1,221,870 km, it is the second-farthest large moon from Saturn and completes a single orbit every 16 days. Like Europa and Ganymede, it is believed that Titan has a subsurface ocean made of water mixed with ammonia, which can erupt to the surface of the moon and lead to cryovolcanism.

Hyperion is Titan’s immediate neighbor. At an average diameter of about 270 km, it is smaller and lighter than Mimas. It is also irregularly shaped and quite odd in composition. Essentially, the moon is an ovoid, tan-colored body with an extremely porous surface (which resembles a sponge). The surface of Hyperion is covered with numerous impact craters, most of which are 2 to 10 km in diameter. It also has a highly unpredictable rotation, with no well-defined poles or equator.

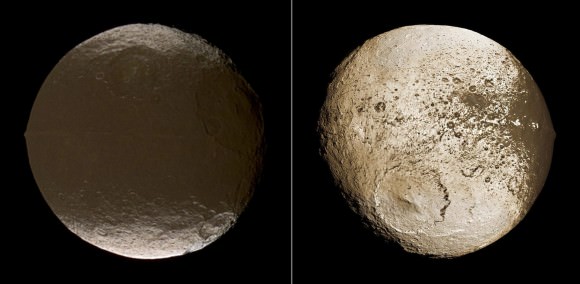

At 1,470 km in diameter and 18×1020 kg in mass, Iapetus is the third-largest of Saturn’s large moons. And at a distance of 3,560,820 km from Saturn, it is the most distant of the large moons and takes 79 days to complete a single orbit. Due to its unusual color and composition – its leading hemisphere is dark and black whereas its trailing hemisphere is much brighter – it is often called the “yin and yang” of Saturn’s moons.

Saturn’s Irregular Moons:

Beyond these larger moons are Saturn’s Irregular Moons. These satellites are small, have large radii, are inclined, have mostly retrograde orbits, and are believed to have been acquired by Saturn’s gravity. These moons are made up of three basic groups – the Inuit Group, the Gallic Group, and the Norse Group.

The Inuit Group consists of five irregular moons that are all named from Inuit mythology – Ijiraq, Kiviuq, Paaliaq, Siarnaq, and Tarqeq. All have prograde orbits that range from 11.1 to 17.9 million km, and from 7 to 40 km in diameter. They are all similar in appearance (reddish in hue) and have orbital inclinations of between 45 and 50°.

The Gallic group consists of four prograde outer moons that are named after characters in Gallic mythology – Albiorix, Bebhionn, Erriapus, and Tarvos. Here too, the moons are similar in appearance and have orbits that range from 16 to 19 million km. Their inclinations are in the 35°-40° range, their eccentricities around 0.53, and they range in size from 6 to 32 km.

Last, there is the Norse group, which consists of 29 retrograde outer moons that take their names from Norse mythology. These satellites range in size from 6 to 18 km, their distances from 12 and 24 million km, their inclinations between 136° and 175°, and their eccentricities between 0.13 and 0.77. This group is also sometimes referred to as the Phoebe group, due to the presence of a single larger moon in the group – which measures 240 km in diameter. The second-largest, Ymir, measures 18 km across.

Within the Inner and Outer Large Moons, there are also those belonging to the Alkyonide group. These moons – Methone, Anthe, and Pallene – are named after the Alkyonides of Greek mythology, are located between the orbits of Mimas and Enceladus, and are among the smallest moons around Saturn. Some of the larger moons even have moons of their own, which are known as Trojan moons. For instance, Tethys has two trojans – Telesto and Calypso, while Dione has Helene and Polydeuces.

Moon Formation:

It is thought that Saturn’s moon of Titan, its mid-sized moons and rings developed in a way that is closer to the Galilean moons of Jupiter. In short, this would mean that the regular moons formed from a circumplanetary disc, a ring of accreting gas, and solid debris similar to a protoplanetary disc. Meanwhile, the outer, irregular moons are believed to have been objects that were captured by Saturn’s gravity and remained in distant orbits.

However, there are some variations to this theory. In one alternative scenario, two Titan-sized moons were formed from an accretion disc around Saturn; the second one eventually broke up to produce the rings and inner mid-sized moons. In another, two large moons fused together to form Titan, and the collision scattered icy debris that formed to create the mid-sized moons.

However, the mechanics of how the moon formed remains a mystery for the time being. With additional missions mounted to study the atmospheres, compositions, and surfaces of these moons, we may begin to understand where they truly came from.

Much like Jupiter, and all the other gas giants, Saturn’s system of satellites is extensive as it is impressive. In addition to the larger moons that are believed to have formed from a massive debris field that once orbited it, it also has countless smaller satellites that were captured by its gravitational field over the course of billions of years. One can only imagine how many more remain to be found orbiting the ringed giant.

We have many great articles on Saturn and its moons here at Universe Today. For example, here’s How Many Moons Does Saturn Have? and Is Saturn Making a New Moon?

Here’s an article about the discovery of Saturn’s 60th moon, and another article about how Saturn’s moons could be creating new rings.

Want more information about Saturn’s moons? Check out NASA’s Cassini information on the moons of Saturn, and more from NASA’s Solar System Exploration site.

We have recorded two episodes of Astronomy Cast just about Saturn. The first is Episode 59: Saturn, and the second is Episode 61: Saturn’s Moons.

Sources:

- NASA- Cassini Mission – Saturn’s Moons

- Saturn’s Moons (European Space Agency)

- Cassini Solstice Mission (NASA)

- Cassini-Huygens (European Space Agency)

- Cassini Imaging Central Laboratory for Operations (CICLOPS)