Astronomers have announced Nobel Prize-worthy evidence of primordial gravitational waves — ripples in the fabric of spacetime — providing the first direct evidence the universe underwent a brief but stupendously accelerated expansion immediately following the big bang.

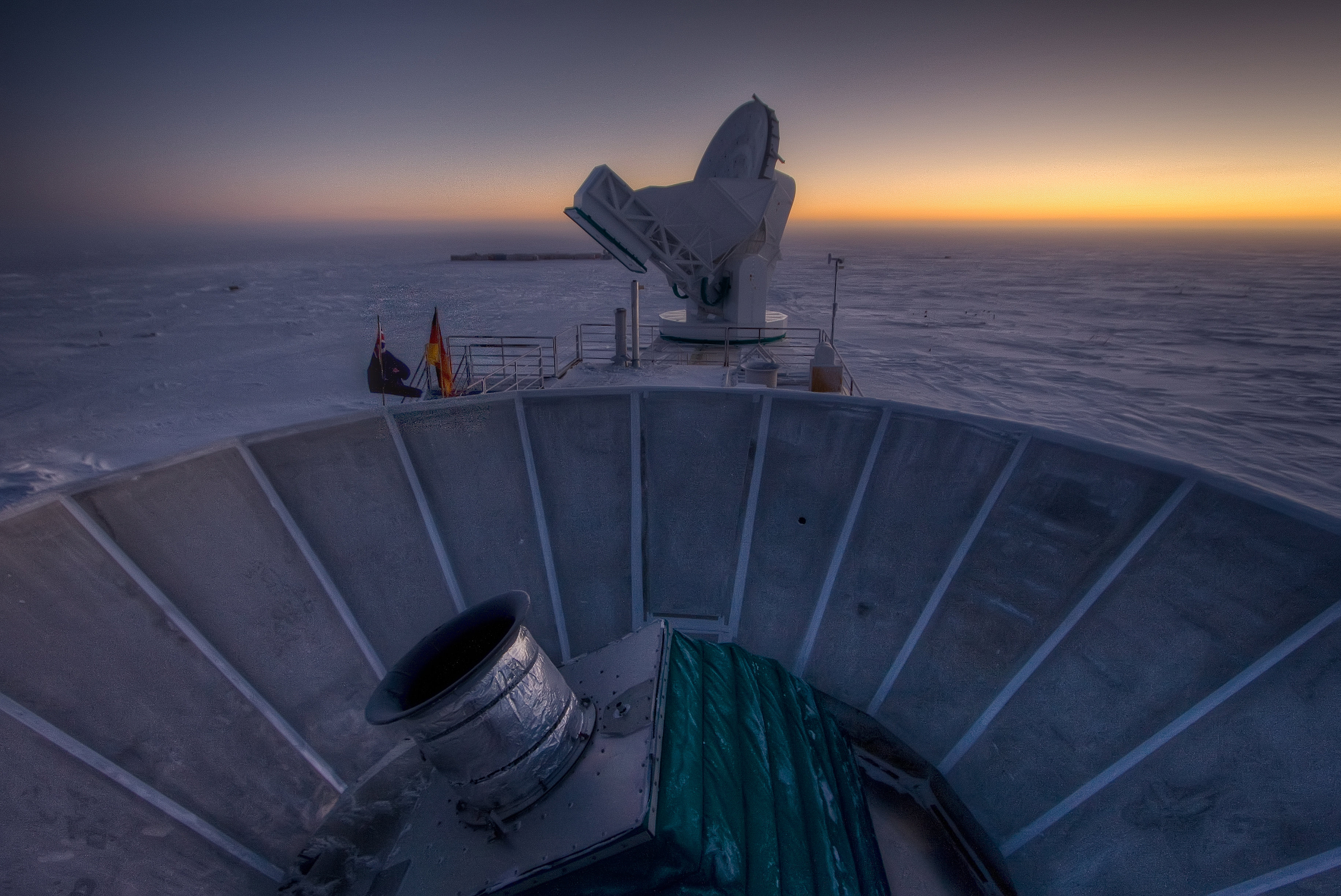

BICEP2 (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization) scans the sky from the south pole, looking for a subtle effect in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) — the radiation released 380,000 years after the Big Bang when the universe cooled enough to allow photons to travel freely across the cosmos.

The CMB fills every cubic centimeter of the observable universe with approximately 400 microwave photons. The so-called afterglow of the big bang is nearly uniform in all directions, but small residual variations (on the level of one in 100,000) in temperature show a specific pattern. These irregularities match what would be expected if minute quantum fluctuations had ballooned to the size of the observable universe today.

So astronomers dreamed up the theory of inflation — the epoch immediately following the big bang (10-34 seconds later) when the universe expanded exponentially (by at least a factor of 1025) — causing quantum fluctuations to magnify to cosmic size. Not only does inflation help explain why the universe is so smooth on such massive scales, but also why it’s flat when there’s an infinite number of other possible curvatures.

While inflation is a pillar of big bang cosmology, it has remained purely a theoretical framework. Many astronomers don’t buy it as we can’t explain what physical mechanism would have driven such a massive expansion, let alone stop it. The results announced today provide a strong case in support of inflation.

In Depth: We’ve Discovered Inflation! Now What?

The trick is in looking at the CMB where inflation’s signature is imprinted as incredibly faint patterns of polarized light — some of the light waves have a preferred plane of vibration. If a gravitational wave passes through the fabric of spacetime it will squeeze spacetime in one direction (making it hotter) and stretch it in another (making it cooler). Inflation will then amplify these quantum fluctuations into a detectable signal: the hotter and therefore more energetic photons will be visible in the CMB, leaving a slight polarization imprint.

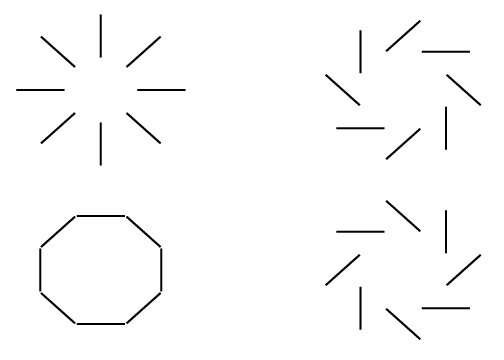

This effect will create two distinct patterns: E-modes and B-modes, which are differentiated based on whether or not they have even or odd parity. In simpler terms: E-mode patterns will look the same when reflected in a mirror, whereas B-mode patterns will not.

E-modes have already been extensively detected and studied. While both are the result of primordial gravitational waves, E-modes can be produced through multiple mechanisms whereas B-modes can only be produced via primordial gravitational waves. Detecting the latter is a clean diagnostic — or as astronomers are putting it: “smoking gun evidence” — of inflation, which amplified gravitational waves in the early Universe.

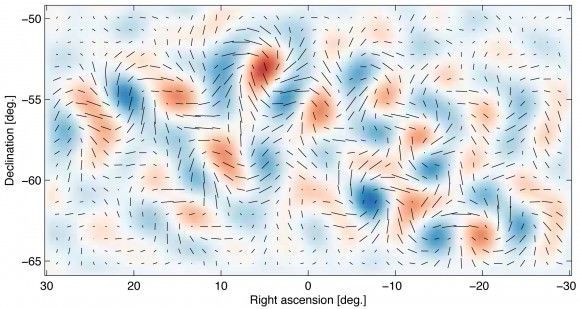

“The swirly B-mode pattern is a unique signature of gravitational waves because of their handedness. This is the first direct image of gravitational waves across the primordial sky,” said co-leader Chao-Lin Kuo from Stanford University, designer of the BICEP2 detector.

The team analyzed sections of the sky spanning one to five degrees (two to 10 times the size of the full moon) for more than three years. They created a unique array of 512 detectors, which collectively operate at a frosty 0.25 Kelvin. This new technology enabled them to make detections at a speed 10 times faster than before.

The results are surprisingly robust, with a 5.9 sigma detection. For comparison, when particle physicists announced the discovery of the Higgs Boson in July, 2012 they had to reach at least a 5 sigma result, or a confidence level of 99.9999 percent. At this level, the chance that the result is erroneous due to random statistical fluctuations is only one in a million. Those are pretty good odds.

While the team was careful to rule out any errors, it will be crucial for another team to verify these results. The Planck spacecraft, which has been producing exquisite measurements of the CMB, will be reporting its own findings later this year. At least a dozen other teams have also been searching for this signature.

“This work offers new insights into some of our most basic questions: Why do we exist? How did the universe begin?” commented Harvard theorist Avi Loeb. “These results are not only a smoking gun for inflation, they also tell us when inflation took place and how powerful the process was.”

Not only does inflation succeed in explaining the origin of cosmic structure — how the cosmic web formed from the smooth aftermath of the big bang — but it makes wilder predictions as well. The model seems to produce not just one universe, but rather an ensemble of universes, otherwise known as a multiverse. This collection of universes has no end and no beginning, continuing to pop up eternally.

Today’s results provide a stronger case for “eternal inflation,” which gives a new perspective on our desolate place within the cosmos. Not only do we live on a small planet orbiting one star out of hundreds of billions, in one galaxy out of hundreds of billions, but our entire universe may just be one bubble out of a vast cosmic ocean of others.

The detailed paper may be found here.

The full set of papers are here.

An FAQ summarizing the data is here.